In 2016, Russian hackers targeted voting systems in 21 states and, according to Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s report, breached systems in Illinois and two counties in Florida, gaining access to information on millions of registered voters. In his report, Mueller described the Russian government’s interference in the 2016 elections as “sweeping and systematic.”

Three years later, security experts warn that not enough has been done to address vulnerabilities in the U.S. election system. The director of the Federal Bureau of Investigations recently told Congress that “the threats just keep escalating,” adding that he viewed the 2018 midterms as a “dress rehearsal for the big show in 2020.”

In fourteen states, some 2018 midterm voters submitted their votes on touchscreens that did not produce paper trails necessary to verify their votes or audit election outcomes. If votes had been inaccurately processed in these precincts—whether through equipment errors or foreign hacking operations—election officials wouldn’t have been able to find or correct the problems.

Several Democratic and Republican members of Congress have submitted legislation to shore up election security. Proposals from Sen. Ron Wyden (D-Ore.), Sen. James Lankford (R-Okla.) and Rep. John Sarbanes (D-Md.) include replacing paperless electronic voting machines with hand-marked paper ballots and optical scanners, subjecting voting equipment vendors to rigorous cybersecurity standards, and requiring vendors to report cybersecurity incidents.

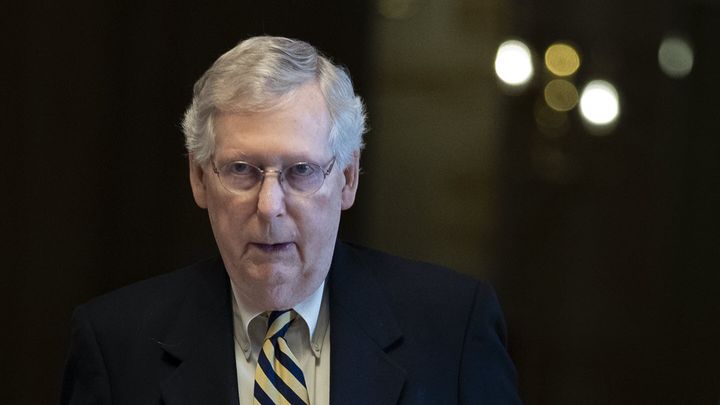

But all the bills have hit a roadblock. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) has reportedly told his colleagues that he will not allow the Senate to vote on election security legislation this session.

The only logical conclusion is that Senator McConnell wants American elections to be vulnerable to hackers and foreign interference.

Sen. Ron Wyden (D-Ore.)

“At this point I don’t see any likelihood that those bills would get to the floor if we mark them up,” Senator Roy Blunt (R-Mo.) said recently when asked by Sen. Dick Durbin (D-Ill.) whether the Rules Committee, which Blunt chairs, would mark up any election security bills. The Hill asked McConnell’s office about Blunt’s comments regarding election security and was referred to the majority leader’s verdict on the Mueller report: “case closed.”

Senator Wyden told Sludge he thinks McConnell does not want to make elections more secure.

“The only logical conclusion is that Senator McConnell wants American elections to be vulnerable to hackers and foreign interference,” Wyden said. “It is unconscionable for Republicans to stick their heads in the sand and do nothing after what happened in 2016. If Congress doesn’t act, it’s only a matter of time before hackers successfully interfere again.”

The two largest voting machine vendors in the U.S., Election Systems & Software (ES&S) and Dominion Voting Systems, together supply more than 80% of the nation’s voting machines. The companies have operated extensive lobbying operations in states for years, and both companies recently hired new lobbyists to represent them at the federal level.

ES&S hired lobbying firm Peck Madigan Jones in Oct. 2018 and paid it a combined $150,000 to lobby the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives in the fourth quarter of 2018 and the first quarter of 2019. ES&S did not employ any federal lobbyists in 2017, and when they reported lobbying in previous years it was at a much lower level, spending just $10,000 in many quarters. Dominion Voting Systems, which was recently acquired by New York-based hedge fund Staple Street Capital, signed its first-ever federal lobbying contract in January 2019 with Brownstein Hyatt Farber and Schreck and has paid the company at least $30,000 so far to lobby Congress.

Several of the lobbyists working for ES&S and Dominion Voting Systems have recently made contributions to McConnell’s campaign and joint fundraising committee.

Brownstein Hyatt Farber and Schreck lobbyist David Cohen, who lobbies for Dominion Voting Systems on issues related to election security and monitors federal legislation for the company, gave McConnell $2,000 on March 31: $1,000 to his campaign committee and $1,000 to his joint fundraising committee. Lobbyist Brain Wild, who works alongside Cohen on the Dominion contract, gave McConnell $1,000 on the same day.

Emily Kirlin, a lobbyist for Peck Madigan Jones who lobbies for ES&S on election security and H.R. 1, gave McConnell’s campaign committee $1,000 on February 19, and her colleague who works with her on the contract, Jen Olson, gave McConnell $1,000 on March 4.

“It’s not surprising to me that Mitch McConnell is receiving these campaign contributions,” the Brennan Center for Justice’s Lawrence Noren told Sludge. “He seems single-handedly to be standing in the way of anything passing in Congress around election security, and that includes things that the vendors might want, like money for the states to replace antiquated equipment.”

“Mitch McConnell’s conflicts of interest in blocking any and all election security legislation is not only shameful, it is placing our democracy at risk,” Craig Holman, government affairs lobbyist at Public Citizen, told Sludge. “The conflicts of interest arise from more than the campaign contributions he is receiving from voting machine vendors—contributions which certainly appear to be a reward from the industry for letting them off the hook—but it is also a self-serving act for strictly partisan purposes.

“McConnell believes this foreign interference in our democratic process will again favor the GOP, and so he is doing everything possible to make sure that window stays wide open for those who seek to do harm to our political system,” Holman said.

McConnell’s office did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

Voting machine vendors like ES&S and Dominion Voting Systems are not currently subject to any specific regulations or mandatory security standards.

“In contrast to other sectors, particularly those that the federal government has designated ‘critical infrastructure,’ there is almost no federal oversight of private vendors that design and maintain the systems that allow us to determine who can vote, how they vote, what voters see when they cast their vote, how votes are counted, and how those vote totals are communicated to the public,” Noren told Congress recently in a testimony. “In fact, there are more federal regulations for ballpoint pens and magic markers than there are for voting systems and other parts of our federal election infrastructure.”

Several of the bills that have been proposed in Congress would subject them to regulation and oversight for the first time, and some could result in the companies doing less business with the states as they encourage the use of hand-marked ballots instead of machines.

A bill from Senator Wyden—the Protecting American Votes and Election Act (PAVE Act)—would, for the first time, establish minimum cybersecurity requirements that election equipment vendors would have to comply with in order for their equipment to be eligible for use in federal elections. The rules would be established by the Department of Homeland Security, and systems would have to be tested and certified by the Election Assistance Commission (EAC).

The PAVE Act would also require voting systems to use an “individual, durable, voter-verifiable, paper ballot of the voter’s vote that shall be marked and made available for physical inspection and verification by the voter before the voter’s vote is cast and tabulated.” And while the bill does not explicitly ban electronic systems for marking paper ballots—something that both ES&S and Dominion Voting Systems have begun manufacturing—it specifies that funding it would give to states to replace their paperless systems could not be used “to acquire any electronic device that a voter can use to mark a paper ballot.”

If a paper ballot requirement were to become law, with or without a funding restriction such as the one included in Wyden’s bill, the increased costs and security risks of ballot-marking machines could make them less appealing to states looking to purchase new systems.

According to testimony from Alex Halderman, Professor of Computer Science and Engineering at the University of Michigan, equipping a precinct with ballot-marking electronic devices costs about three times as much as equipping it with a truly paper-based system along with a dedicated electronic device for voters with disabilities. “Fortunately, the most cost-effective approach is also the most secure: hand-marked paper ballots counted using optical scanners,” Halderman stated.

Another bill being blocked by McConnell, the House-passed H.R.1, includes a paper ballot requirement and would subject vendors to additional new security regulations. Voting machine vendors would be required to follow cybersecurity best practices that would be issued by the EAC’s Technical Guidelines Development Committee, and they would have to report election cybersecurity incidents and response plans to the EAC. They would also be forced to submit their equipment to independent security testing, and the EAC would be empowered to decertify any equipment that does not meet its security standards.

“I don’t know why Mitch McConnell is staging a full roadblock of election security legislation,” Wyden said. “But it is clear as day that there are politicians in the country who view insecure voting equipment as a benefit that helps them win elections. Instead of defending Americans’ constitutional rights, they are looking at this issue from a purely cynical and political standpoint.”