People who have given money to a candidate for state house or city hall belong to a rare club. Only 2% of the voting age population have made a donation to a candidate for state-level office, according to a recent report from the think tank Campaign Finance Institute.

Around the country, states and cities are experimenting with programs to democratize campaign finance—giving candidates a broader base of potential donors and amplifying the impact of small-dollar donations.

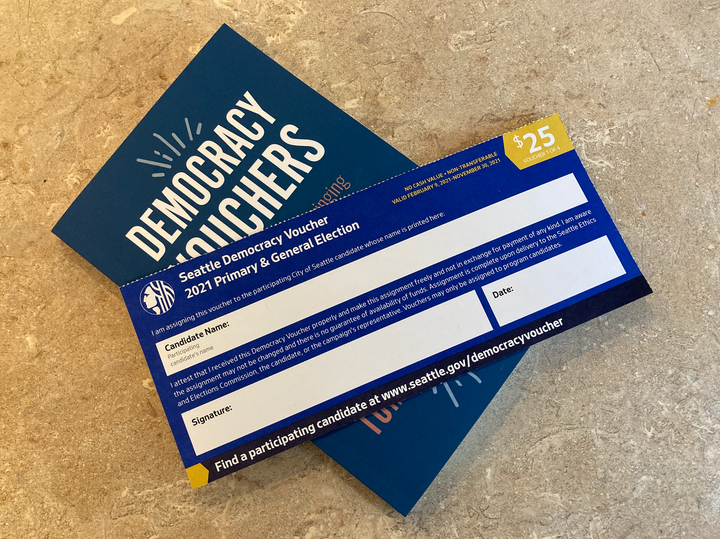

One example is a unique public campaign financing program now in use in its third election cycle in Seattle that sends four $25 “democracy vouchers” to every registered voter, who can issue them in paper form or online to participating campaigns to be redeemed for funding. A comprehensive new book, “Democracy Vouchers: How bringing money into politics can drive money out of politics,” covers the design of the program and how it works to curb the influence of big donors.

Written by Tom Latkowski, policy organizer with the Democracy Policy Network, and with a foreword by anti-corruption scholar Lawrence Lessig, the book makes the case that vouchers offer one of the most powerful tools yet for increasing public engagement in the election process. A paperback copy runs about $10 and a digital copy of the book can be had for $5.

Sludge spoke with Tom from his home in Los Angeles about this innovative program to counter disengagement from Big Money’s outsized spending in elections.

How did this book come about?

I started working at the Democracy Policy Network two years ago. Our model is to help progressive state legislators—we’ve seen lots of people come into office with bold ideas, but then they might only have one and one half-time staff members, not enough to handle 500 or 1,000 policy topics. The idea is to do the research, compile a list of experts in a policy bullpen, and hold events with legislators.

I produced the kit on democracy vouchers, and then I wanted to do something a bit bigger—to go more broadly into the history of money in politics. In the book, I go back to Theodore Roosevelt, to the first scandals relating to his campaigns, and look at how we’ve gotten here, where so many reform options are closed off when the Supreme Court won’t limit outside spending.

Public financing solves many of the problems we want to fix: it increases political engagement, makes donors become more representative, and helps candidates run for office even if they don’t have a wealthy fundraiser network. All these things we can do with a program that’s constitutional.

What have researchers seen in Seattle’s experiment with democracy vouchers?

In Seattle’s program and its effects, we’ve seen these ideas be used successfully. Donors are now more diverse racially, in terms of income, in terms of where they live. A great statistic from Seattle was that the most significant indicator in whether someone was a donor was whether their address had a view of Lake Washington or Puget Sound—it was all about wealth, but that’s no longer true. They’re more diverse in terms of age, particularly in the last election—more folks under 30, and under 35, are using their vouchers.

We’ve seen more candidates use the program as well. For the first time in Seattle’s history, the two frontrunners are both people of color. Folks of color are disadvantaged by the typical campaign finance system. It’s hard if you don’t have wealthy fundraising connections, who tend to be whiter folks in many cities and states, and it’s also hard if you go to donors—they might like your policy ideas, but wonder if you’re electable. In Seattle, that’s no longer an issue—you no longer have to go to wealthy donors to get your campaign off the ground.

The third part is the political engagement piece. There is evidence that voucher users were more likely to vote than other registered voters. Our best guess for this causal mechanism is that if you have a conversation with a candidate and they ask you for your vote, that is a conversation that most people never have, in most cities and states. It’s hard to have a conversation with candidates. In Seattle, candidates are incentivized to do that.

When designing the program, I’ve spoken to a number of advocates: they want hardened political operatives who are advising candidates for city council to think that this is a smart program for their candidates. This is what a smart program can do: have the most strategic choice for a candidate or campaign to make it be the very thing that we want to see in the community, and political engagement is a perfect example of that.

You’re also the co-founder of Los Angeles for Democracy Vouchers—tell us about that campaign.

In Los Angeles, 99.85% of the population didn’t give a single cent to City Council or school board candidates. In the 2020 election cycle, only 5,463 Angelenos donated—70 percent of the individual donations came from ZIP codes that are outside Los Angeles, including Park City, Utah, and Bentonville, Arkansas, which you may know as home of Walmart and the Walton family. Non-residents and special interests make up over 83% of the money in L.A. elections. Los Angeles is roughly 70% people of color, but the campaign money comes from the areas of the city with the most white residents.

We’re looking at running a ballot initiative—we’re in the stage where we’re talking with community advocates. Our central goal with the L.A. campaign is to make it more than about good governance, to feature the racial justice and gender justice piece, because campaign finance affects which policies can get passed.

Sludge has been covering the Seattle experiment with democracy vouchers since 2018, including ongoing research that shows the program’s effects on increased diversity in candidates and the donor base. A reform group in Washington state, Fix Democracy First, is advocating to bring a version of Seattle’s democracy voucher option to statewide elections. In the 2019 elections in Seattle, the voucher system helped candidates backed by grassroots donors compete with a deluge of last-minute spending in city races by Amazon and the PAC of the Seattle Chamber of Commerce. In five of seven City Council races, the business-backed candidate did not prevail, and in one district the winning candidate was supported by both business and labor groups, demonstrating that vouchers provided support for the vast majority of candidates favored by small donors.

In response to Amazon’s unprecedented $1.5 million in outside spending just weeks before the 2019 contests, in January 2020, the Seattle City Council unanimously passed a ban on political spending by “foreign-influenced corporations,” applying to corporations with a non-U.S. investor holding at least 1% ownership, which includes Amazon. The measure also prohibits corporations from routing their spending through PACs.

In this year’s August primary elections in Seattle, which included the nonpartisan mayoral primary, the Chamber of Commerce largely sat out of election spending on things like mailers supporting or opposing candidates.

All of the major primary candidates in the race for Seattle mayor used the voucher system, including the top two vote-getting candidates—sitting City Council President Lorena González and former Council president Bruce Harrell. González raised $568,225 through vouchers, making up 97% of her campaign’s contributions as of Sept. 20, while Harrell raised $525,950 through vouchers, making up a bit less than two-thirds of his total contributions. Seattle’s next mayor will be a candidate who endorsed the city’s 2015 democracy vouchers ballot initiative.

A 2018 report from the University of Washington, “Expanding Participation in Municipal Elections: Assessing the Impact of Seattle’s Democracy Voucher Program,” found that low-propensity voters who used democracy vouchers were more than four times as likely to vote in the 2017 election.

For more research on the effects of Seattle’s public campaign financing system, see the Dec. 2019 article, “Diversifying the Donor Pool: How Did Seattle’s Democracy Voucher Program Reshape Participation in Municipal Campaign Finance?” by Brian J. McCabe, associate professor in the Department of Sociology at Georgetown University, and Jennifer A. Heerwig, associate professor in the Department of Sociology at Stony Brook University.

Earlier this year, the two professors wrote for Sludge that in the 2019 election cycle, more than 8 percent of Seattle adults used their democracy vouchers or made a cash contribution, up from fewer than 1.5 percent before the program was established. “With enough grassroots support, candidates can raise all the money they need from local residents through the Democracy Voucher Program,” Heerwig and McCabe wrote.