Five years ago, Seattle voters passed an innovative ballot measure that aimed to transform city elections through a “democracy voucher” program. By having the city send four vouchers worth $25 apiece to all registered voters, who could give them to participating candidates in municipal elections who agree to observe individual contribution limits, Seattle voters sought to diversify campaign donors and increase participation in elections. The ballot measure campaign’s website stated it was working “to encourage a more diverse pool of candidates for elected office and ensure everyone has the opportunity to have his or her voice heard, not just the wealthy and political elite.”

The results from the program’s first run in the 2017 election cycle, which covered two city council races and the city attorney contest, showed positive results toward bringing more Seattleites into the campaign system. Democracy vouchers doubled the number of people making donations compared to cash donors in that election cycle, and voucher users were more representative of the city’s population in terms of age, race, and income, according to research by Jen Heerwig, associate professor of sociology at SUNY-Stony Brook.

The voucher program’s second go-around was in the 2019 elections, including seven city council races, and a just-released study shows continued gains in adoption by Seattle residents. Democracy voucher users nearly doubled their number compared to 2017, according to “Building a More Diverse Donor Coalition” by Professor Heerwig and Brian J. McCabe, associate professor of sociology at Georgetown University.

While the increased participation rates were not found to be equally distributed across all socio-demographic groups, voucher users in 2019 further increased their representativeness of the city population. In 2015, before the voucher program started, only 1.3% of Seattle residents donated in city elections; after two cycles with democracy dollars, Seattle is by far the leader nationally in donor participation, with close to 7% of the voting age population using vouchers and 3% giving cash (some using both).

Democracy vouchers are set to have even greater impacts on Seattle politics next year, after Mayor Jenny Durkan announced earlier this month that she would not seek re-election. The nonpartisan primary election on Aug. 3 and general election on Nov. 2 will be the first where democracy vouchers are in play for the mayorship.

One Seattle public radio host described Durkan’s announcement as a surprise, coming from an incumbent who had launched a re-election campaign in February, while other city political writers found the decision less unexpected, given a year of intense controversy around protests in Seattle against police brutality and the strain of the coronavirus pandemic. In the days after Durkin announced her decision not to run, city hall observers began surveying what is likely to be a large group of mayoral candidates.

The public financing option could help grassroots campaigns based on vouchers mount an effective challenge to more establishment, wealthier, or business-backed candidates.

Voucher Users Look More Like Seattle

Heerwig and McCabe told Sludge that even though the voucher participation rate increased substantially, it was not increasing evenly across the Seattle population.

“Certain folks, including white residents of Seattle, those with higher incomes, and older residents, were more likely to participate,” said Heerwig.

Last year, 38,297 Seattle residents donated 147,892 vouchers, according to the Seattle Ethics and Elections Commission, which administers the program. More than 80% of them were first-time voucher users who had not participated in 2017. The number of voucher users in 2019 doubled the number of cash donors, which was 16,926; in 2017, there were 20,727 voucher users and 10,297 cash donors.

“Even though participation rates were not even across races, the composition of voucher users looks more like voters than do cash donors who gave at least $25,” Heerwig said. “That’s particularly true in most of the city council districts that had candidates that were participating. So even though that participation rate has not been even across groups, we do observe that the voucher users were more representative than cash donors.”

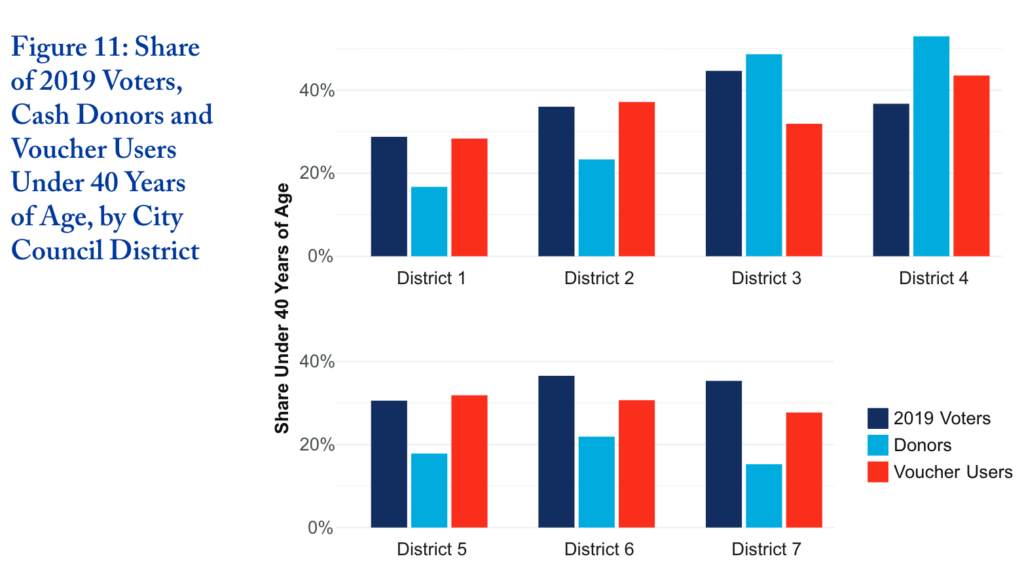

While participation grew among all races, voucher pickup among white residents increased by the largest amount, stepping up from 4.3% in 2017 to 7.67%, the study found. Participation among Black residents rose from 2.4% to 3.1%, and among Asian residents from 2.46% to 3.65%. In five of seven council districts, voucher users under 40 years of age made up a higher share of donors than cash donors. (In the other two districts, small-donor participation overall was the highest among the seven districts, counting both vouchers and cash donors, due to local political factors.)

Participation similarly increased over 2017 among all income quintiles, with the greatest gains among households with incomes over $100,000, rising from 5% to 13%. Gains among residents under $30,000 in income rose from 3.09% to 4.62%, the study found.

“The question that this empirical stuff asks is, What can Seattle and community group partners do to get more lower-income folks involved?,” said McCabe. “There’s been a concerted effort to do outreach to lower-income communities by partnering with different community groups in Seattle, and non-English language communities. This looks like voter participation, where lower-income and historically-marginalized groups participate at lower rates.”

Seattle’s program allows voters to give vouchers to candidates outside of their districts of residence, which one-third of users did. This feature, Heerwig and McCabe said, led to some interesting findings—younger, lower-income and non-white voucher users were more likely to give across district lines, including 51.6% of the youngest users age 18-29. “One hypothesis is that voucher users were actually giving to candidates that looked more like them,” McCabe said. “The way you grow participation in the program might be on the candidate side, if they’re more representative of their communities. The goal is to enable a more diverse group of candidates to run for office, and as a result, bring more donors into the fold into local politics.”

Supporters of public financing of elections—of which democracy vouchers are one type, in effect only in Seattle so far—have highlighted the program’s effects on candidates as well, by expanding the pool of individuals who choose to run for office. Grassroots candidates who don’t bring with them wealthy donor networks have said such programs open up a path to mounting a strong campaign or challenging incumbents who are backed by business interests.

Showdown with Amazon’s Cash Barrage

Last year in Seattle, 53 candidates pledged to participate in the voucher program, with 35 meeting the qualifying requirements in seven of nine city council districts. All but two of the 14 candidates who advanced to the general election participated in the program. One of the two candidates who did not participate, incumbent Kshama Sawant in District 3, reaffirmed her support for the progressive program. The other, challenger Ann Davison Sattler in District 5, changed her party affiliation to Republican earlier this year in a bid for lieutenant governor, after losing in 2019. A third city council candidate last year, Shaun Scott, participated in the program but also had cultivated a diverse coalition of small-dollar contributors, which raised the total number of cash donors in District 4.

Sawant said that hefty outside spending in her race by corporate interests like Amazon caused her to opt out of the voucher program, which requires candidates to abide by spending limits. The democracy voucher program includes a provision that allows the spending caps to be lifted if outside spending reaches certain levels, and most candidates did request the $150,000 cap be lifted after expenditures by an outside committee topped $75,000 in their races. The PAC of the Seattle Chamber of Commerce, Civic Alliance for a Sound Economy (CASE), ended up splashing out $1.8 million across city council elections, of which $1.5 million came from Amazon. Of that amount, Amazon announced it would toss in $1 million on Oct. 15, 2019, three weeks before Election Day. Days before the election, Rep. Pramila Jayapal (D-Wash.) said, “This most recent influx of money from Amazon is callously disrespectful to the residents of our city. It says loud and clear that some people are afraid of letting real democracy work for the people.”

Overall spending on Seattle city council elections in 2019 was more than double what was spent on the 2015 races, which had nine council seats up for election, compared to seven seats last year. Spending from outside PACs made up 55% of the total last year at over $4 million, up from 20% in 2015, when PACs spent $670,000. Democracy vouchers made up almost 20% of spending at over $1.4 million in the 2019 cycle, and cash contributions made up the remaining quarter, at over $1.8 million.

In five of the seven city council races, the business-backed candidate did not win, despite greater spending by CASE—in the case of District 6’s contest, over five times more for Heidi Willis than the sum that went to support successful challenger Dan Strauss. (In one of the other contests, incumbent Debora Juarez was backed by both business and labor interests.) Sawant, who had led a council effort to implement a payroll tax on Amazon that was repealed in 2018 after a campaign by business groups, said last year, “The election results are a repudiation of the billionaire class, corporate real estate, and the establishment.”

Rory O’Sullivan is a Seattle resident who was one of the authors of Honest Elections Seattle, the sweeping ethics initiative that created the voucher program and was approved with 63% of voters in support in 2015. He’s currently the chair of the board of the non-profit, non-partisan FairVote Washington, which advocates for ranked-choice voting. He told Sludge, “One thing we found in research, the causality is not that the most money always wins, but research shows it’s imperative to have a baseline of funding. What you can demonstrate statistically is that if you reach a certain base of funding, additional dollars have much lower impact. What we wanted when designing the program was that any candidate who wanted to use vouchers could reach a threshold to get their message out to voters and be competitive.”

Last year’s expanded go-around with the democracy voucher program was not assured, as two property owners had brought a constitutional challenge to the city-wide system on the basis that its use of tax payments forced them to support candidates they opposed. In July 2019, the Washington Supreme Court unanimously ruled that the vouchers do not restrict anyone’s free speech rights. On March 30, 2020 the U.S. Supreme Court turned down an appeal without comment, clearing the way for the city’s pioneering experiment with vouchers to continue.

Democracy vouchers may be weighed by voters in a second municipality, as supporters in Austin, Texas seek to place a measure on the ballot in May 2021 that also proposes four $25 vouchers per voter, for eligible candidates in voters’ districts and mayoral candidates. The campaign’s website says their plan carries an annual price tag of less than $850,000 and aims to take effect in the 2022 election cycle.

The sweeping campaign finance reform bill H.R. 1, the For the People Act, passed by House Democrats in March of 2019 along party lines, includes a voucher pilot program based on the Seattle model where the Federal Election Commission would select three states for a trial run with congressional candidates. The pilot program was added to the bill through an amendment from Rep. Jayapal.