In the city of Baltimore, the demographics of donors to political campaigns have been nearly a perfect inverse of the city’s population. Donors to mayoral and City Council races in 2015 and 2016 were 64% white and 32% Black, while 32% of Baltimore residents were white and 63% of residents were Black, according to a report from the non-profit think tank Demos.

Half of Baltimore families make $44,000 or less per year, the report found, yet nearly half of all contributions came from households making over $100,000. Among the donor class, other races and ethnicities were almost unrepresented.

This Election Day, voters in Baltimore County will be able to give the green light to a public financing program for county elections that aims to help more candidates run for office and amplify the impact of small-dollar donations, while curbing the influence of deep-pocketed donors.

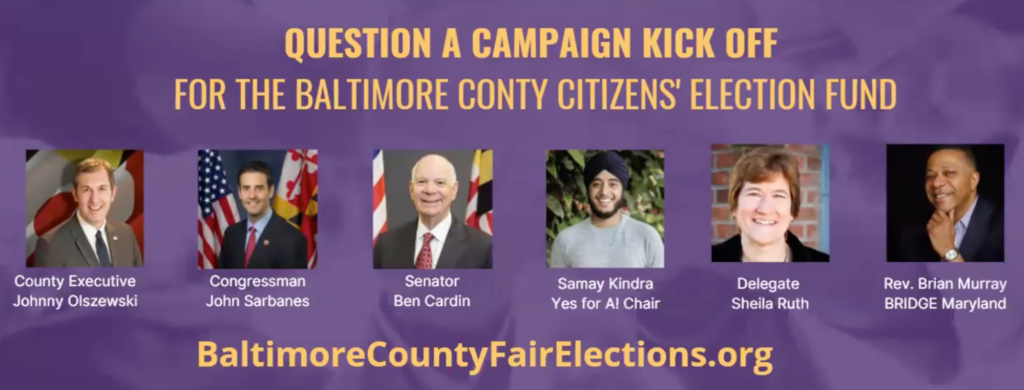

Last week, a coalition of Maryland groups launched the Vote Yes for A campaign, supporting a charter amendment that would create a voluntary “Citizens’ Election Fund” program for participating candidates starting in 2026. The Oct. 6 kickoff event, with a 15 minute video viewable on Facebook, featured Baltimore County Executive Johnny Olszewski Jr., joined by Samay Kindra, chair of the “Yes for A” campaign, and leaders from two of the at least 15 endorsing groups, Common Cause Maryland and Progressive Maryland.

The Baltimore County measure comes after a number of other Maryland jurisdictions—including its two most populous counties, Montgomery and Prince George’s, as well as Howard County and the city of Baltimore—have in past years established public financing programs. A study by Demos of public funding options found that matching funds have been shown to increase donor participation in municipal and state elections, also increasing racial and class diversity among donors.

Programs like this allow candidates and incumbents to change the way they’re running, on the strength of the constituents they are seeking to represent, to help build a more inclusive and representative democracy.

Joanne Antoine, executive director, Common Cause Maryland

Montgomery County, part of the Washington D.C. corridor, enacted its public financing program in 2015, with a design largely similar to other matching programs nationwide: first, candidates opting in agree to not accept donations over $150 or contributions from corporations, unions, or PACs. Qualifying candidates then are eligible to receive funds according to a ratio where the first $25 is a 9 to 1 match, the second $50 is a 5 to 1 match, and the remaining $75 is a 2 to 1 match, with caps on funding from the government depending on the level of office sought.

The Montgomery County design was picked up by voters in the city of Baltimore for their public financing program, was endorsed by over 75% of voters in a 2018 ballot measure and approved by the Baltimore City Council on Dec. 2, 2019.

The seven-member Baltimore County Council first approved Measure A on March 30, 2019, by a vote of 5-2, with bipartisan support. The Council’s four-page bill can be read here. While ballot measures to adopt public financing had been passing across Maryland, the Baltimore County Council bill arrived the same month that high-profile corruption allegations were breaking in the area. On May 2, 2019, former Baltimore Mayor Catherine Pugh had her lawyer announce that she was resigning amid scandal over profiting from bulk sales of self-published children’s books. In February, Pugh was sentenced to three years in prison on fraud and other charges.

In a recent editorial endorsing Measure A, the Baltimore Sun called it “among the most important decisions county voters face this November.” The editorial drew attention to the success of the Montgomery County public financing program, where candidates who opted in averaged donations of $86 while those who did not averaged $1,145, according to a report from the grassroots organization Maryland PIRG.

Joanne Antoine, executive director of the nonpartisan advocacy group Common Cause Maryland, told Sludge that when County Executive Olszewski committed to making sure campaign finance reform was his first legislative initiative, grassroots Maryland groups were ready to help bring the Montgomery County program to Baltimore County. Antoine says a forthcoming report from Common Cause Maryland ran the numbers on the recent cost of running for office in Baltimore County: on average, council candidates raised nearly $104,000, and county executive candidates raised $1.031 million in the 2018 election cycle.

“Right now, unless you have access to folks with a large amount of money, you’re not able to run a competitive race,” Antoine told Sludge. “When you look at the past few election cycles, very few women have run—right now there’s only one woman on the County Council, and access to funding has been one of the barriers. A citizens’ election fund will allow more candidates, and more diverse candidates, to run and win races and better reflect the people of Baltimore County.

“When it costs nearly a million dollars to run for office, you have no choice but to go to corporate donors and high dollar individuals,” Antoine said. “Programs like this allow candidates and incumbents to change the way they’re running, on the strength of the constituents they are seeking to represent, to help build a more inclusive and representative democracy. Where some candidates only visited communities during the peak of GOTV, in Montgomery County public financing was a real shift. Voters were also more educated— we had residents asking questions about how to look through the campaign finance system.”

Larry Stafford, Jr., an organizer and executive director with Progressive Maryland, spoke at the campaign launch event about his experience seeing the Montgomery County election system transformed by a fair elections fund.

“The theme in local elections had been, these are contests for those who have the access to the most resources, for those who can raise hundred of thousands of dollars from a network of friends or their own personal wealth,” Stafford said. “Now, we had over 30 candidates who ran for public office, many of them for the first time in their lives, and who used this system to run campaigns that were much more competitive than they would have been before. The result was that you had small donors in communities who were able to give to campaigns and feel like the small amount of money they had was able to go a lot further. Your $20, or $5, meant a lot more than it would have without a fair elections fund, and it forced candidates to campaign directly to their voters,” Stafford said.

Emily Scarr, the state director of Maryland PIRG, an independent citizen-funded organization that helped coordinate the coalition of groups behind the Measure A outreach, says that the Baltimore County campaign has been a bit different this year because of the coronavirus pandemic. “We moved our work online—we’ve always done house parties, to be able to talk to people about fair elections for periods of time, but we’ve shifted to Zoom,” Scarr told Sludge. “We’ve held discussions with community organizations, remote events with community leaders, phone and text banking, letter writing and post-carding.” A 54 minute Zoom recording of the coalition’s virtual kickoff event, which also includes Jews United for Justice and The League of Women Voters of Baltimore County, can be watched online.

Research continues to find that in most states and cities since the 2012 elections, the share of $1,000+ contributions dominates that of small-dollar donations. Compared to campaigns fueled by large checks from a smaller base of more-affluent donors, publicly-financed campaigns have robust incentives to remain responsive to all of their constituents, as shown by the positive results from New York City’s leading matching system. With the cost of running for Baltimore County Council seats increasing, Scarr noted, “This can lead to influence from large corporate donors or real estate developer interests, whether actual or the perception.”

In Howard County in 2016, a political action committee had formed in opposition to the public financing ballot initiative there. The committee’s treasurer held the same role for the campaign of Howard County Executive Allan Kittleman, a Republican former state senator who opposed the county’s ballot measure.

The Baltimore city and county public financing programs would be administered separately for their council and executive elections; according to population data from the U.S. Census as of 2019, the independent city of Baltimore had approximately 594,000 residents and the municipal county around it had about 827,000 residents.