New York politics has infamously been dominated by powerful bosses with deep ties to moneyed interests—so much so that the state Senate and Assembly leaders were each convicted of corruption in 2018, as have five close associates of Democratic Governor Andrew Cuomo in recent years.

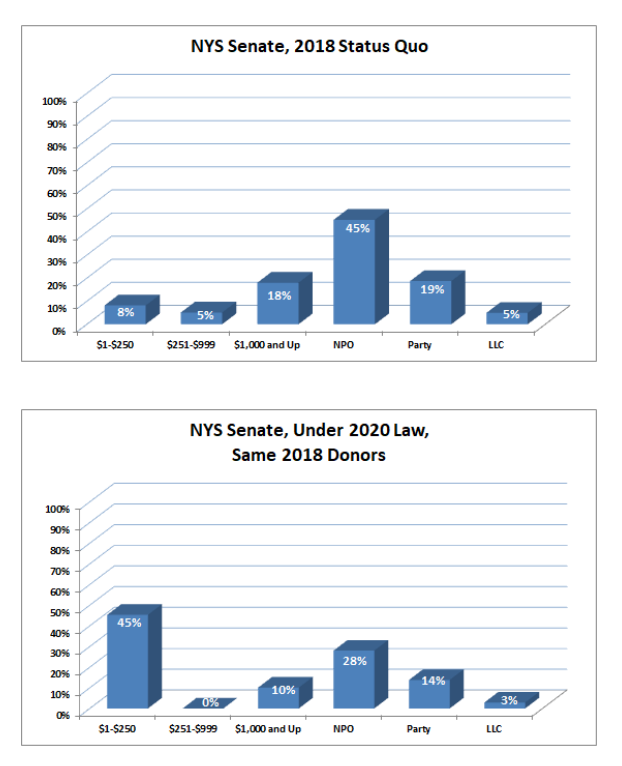

For new candidates or those taking on establishment figures, raising the funds for a competitive campaign can be challenging. New York senators and assembly members received about 45% of their campaign funding in the 2018 cycle from large donations made by PACs and private companies. Challengers typically can’t raise money from those sources, and the small donors who they have to rely on are not very active in the state. According to a January report by the Campaign Finance Institute, just 8 percent of contributions to New York Senate candidates in 2018 came from donors giving under $250; for Assembly candidates, just 14 percent.

This year, the coronavirus pandemic and social distancing guidelines have heightened the challenge for new candidates, who have had to run grassroots campaigns without the in-person events that typically make up their schedule and help them build their supporter base.

Samra Brouk, a native of Rochester, New York, is a former Peace Corps volunteer and nonprofit professional who is running for the state Senate on the Democratic and Working Families Party ballot lines. Like other campaigns impacted by the coronavirus pandemic, Brouk’s bid for office as the first African-American woman to represent the 55th Senate District has had to pivot from face-to-face interactions with voters to video chats and phone calls.

“When we were in the thick of COVID-19, people were worried about their health, there was a lack of consistent information, it was hard to focus on an election,” Brouk told Sludge. “Folks lost their jobs, some didn’t have food on the table, so we just called to check in. We had an incredible group of volunteers who jumped right in, calling thousands of seniors, checking on groceries, checking what was working, being responsive.”

Responsiveness has not been a term often associated with the New York Assembly and Senate for much of the past decade, as ethics experts and community groups have decried the legislature’s gridlock, heavy lobbying culture, and influence by special interests. A 2015 report by the Center for Public Integrity slapped New York state government with an ethics grade of D-minus, describing the state as “beset by corruption, backroom deals and voter scorn.”

But change may be coming to help challengers and new candidates compete against entrenched incumbents and big-money politics. The 2020 New York state budget included a public matching system for campaign financing that is set to take effect after the November 2022 election, enabling small-donor-backed candidates to run competitive campaigns—though the public funding for elections was passed as part of a law that also set new ballot access requirements, which are currently subject to legal challenges.

“Public financing of elections—which means true small donor matching funds—will open doors for qualified candidates to run for office, and curtail the pay to play culture in our politics,” Susan Lerner, executive director of Common Cause New York, told Sludge. “The pandemic has only heightened the need for true campaign finance reform that restores accountability to the voters, and gives average people a place at the table.”

For community-focused candidates like Brouk, a public finance matching system would empower them to mount strong campaigns.

“When I think of myself, the daughter of a first generation immigrant, an African-American woman from a middle-class family, the way things are usually set up, I’ve been left out of opportunities to run for office,” Brouk said. “I don’t have millions in the bank, I can’t self-fund, so I am dependent on building a coalition of people who believe in the change I seek to make in our community.”

In future campaigns, Brouk said, being able to take advantage of public matching for small-dollar donations—which she says she “definitely” would opt-in to use, if the program becomes available—would increase representativeness. “Anything that allows us to re-democratize our democracy, more representation through small donors is always going to be a good thing for New York—it allows more people to take part in this process.

“By not being able to have the interactions and conversations that naturally come at the doors, we’re at a disadvantage,” Brouk said, “so we’re trying to be really creative with face-to-face video conference calls.”

Sam Fein is a grassroots candidate running for Assembly in the 108th District around Albany against five-term Assembly member John McDonald, who has raised over $423,000 in his career according to the National Institute on Money in State Politics. Fein’s primary campaign on the Democratic and Working Families Party ballot lines, from his current position in the Albany County legislature, would typically rely on local outreach against an incumbent who has received large donations from the pharmaceutical industry, but the coronavirus has made that difficult.

“I’m disappointed we couldn’t go door to door, we’d normally be knocking on every door,” Fein told Sludge, “so we’re making thousands of phone calls, reaching out through social media, virtual town halls and events. We’ve found a lot of other ways to reach people.

“It’s difficult asking people for money when people are struggling financially during the pandemic,” Fein said, “so instead of having in-person fundraisers, we’re having virtual house parties on Zoom, with friends, supporters, and neighbors, not high-dollar donors.”

Fein said that having the matching fund system in place would have helped his campaign and others in the state who are going up against establishment figures.

“I wish it were in place now, it would really level the playing field between challengers and incumbents, give power back to the people,” Fein said. “So many people have lost hope because they see the government doesn’t respond, this will ensure that a regular person has the same voice as a corporation.”

Fein highlighted the difference in his and McDonald’s backers as disclosed in the 32-day pre-primary reports: “We’re funded exclusively by individual donors, he had only 11 individual donors and almost entirely corporations and PACs.”

Multiplying Small-Dollars for Fair Elections

After a wave of progressive Democrats took a majority in the obdurate state Senate in the 2018 elections, a broad coalition of more than 200 groups called Fair Elections for New York came together to make a push for legislative action addressing Albany’s notoriously lax campaign finance practices. One of the main reforms the coalition organized around was for New York’s 2019 budget to include the option for state candidates—for governor, statewide office, and Senate and Assembly—to use a public matching funds system to help fund their campaigns.

Fair Elections NY’s statewide proposal was broadly modeled after the successful New York City public matching funds program, enacted in 2001. According to a 2010 study by the Brennan Center for Justice, New York City’s system providing matching funds (initially six-to-one) for qualifying and participating candidates worked to enhance diversity in candidates, enable more grassroots campaigns to run in competition with well-connected special interests, and increase donor participation and voter engagement.

New York City’s matching system was strengthened by 80 percent of voters in a 2018 ballot initiative, and its design was largely followed by the public financing option for federal candidates in congressional Democrats’ sweeping reform package, H.R. 1, which passed the U.S. House in March 2019 but is unlikely to be picked up by the U.S. Senate this year. By bringing a public match statewide, coalition groups including the grassroots organization Citizen Action of New York and the nonpartisan good government organization Common Cause New York sought to pass stronger measures to “limit big money in state politics.”

In New York’s government, where decisions have historically come down from “three men in a room,” the resulting campaign finance reform was slow-walked over the course of 2019 and then rushed to its conclusion at the end of the year.

In the New York budget finalized in March 2019, legislative leaders committed to a commission that would design a public matching funds system, with Gov. Cuomo saying that formally adopting a system in the democratically-elected legislature would be “too complicated.” The resulting nine-member commission ended up passing a mix of recommendations in its last meeting on Dec. 1, 2019, a day before it was due—a process marred by last-minute changes through re-votes, with little public explanation.

First, while lowering individual contribution maximums to candidates, the caps put forth by the commission are still high compared to other states. Spurring the most outcry, the reform commission also raised the number of signatures needed for ballot access, striking a blow to smaller political parties and the practice of “fusion voting” often employed by the Working Families Party, wherein people can vote for the same candidate in a race on multiple ballot lines.

Notably, the higher ballot access requirements start immediately and could benefit Cuomo, whose reelection campaign in 2022 will not be held with a public matching option for any gubernatorial rivals. Making it much tougher for third parties to appear on the ballot has been a goal of Cuomo, who battled the WFP in recent years over endorsements of progressive challengers. The public matching option and campaign contribution limits would not take effect until after the statewide election of 2022, in part because of preparation time and in part because the governor’s four-year term was already underway last year.

The public financing system approved by the commission did make some enhancements to New York City’s proven-successful system that make it the first of its kind nationally. To qualify for public funding, state Senate candidates will need to raise $12,000 from a minimum of 150 donors in their district giving $250 or less; Assembly candidates will need at least $6,000 from 75 donors, under the same conditions. Candidates for governor need 5,000 donors totaling $500,000 in aggregate donations of $250 or under; other statewide candidates need 1,000 donors totaling $100,000.

After meeting those qualifying thresholds, further small donations would be matched according to tiers: the first $50 would be matched at a 12:1 rate; the next $100 would be matched at a 9:1 rate; the next $100 would be matched at an 8:1 rate. Each type of participating campaign is bound by maximum funding it can receive—statewide candidates up to $7 million, Senate up to $750,000, and Assembly up to $350,000—and is restricted to spend only from this pool of public funding.

After the commission approved its recommendations on Dec. 1, 2019, they were struck down on March 12, 2020 by a New York state Supreme Court judge in Niagara County, who ruled the commission lacked the authority to make binding changes to the law. But on April 1, 2020, the state legislature simply approved into law the same result from the commission as part of the budget bill—although without a severability clause, meaning that if part is struck down in future legal proceedings, the whole law could fall. The Working Families Party recently filed a federal lawsuit against the higher ballot access thresholds, as previously had a very-minor state party, The Serve America Movement, or SAM, back in January.

Reconnecting Government with the People

Michael J. Malbin, the co-founder and executive director of the Campaign Finance Institute (CFI) and a professor of political science at SUNY-Albany, told Sludge that the commission’s plan was designed to increase political representativeness at the local level.

“The New York Reform Commission allowed gubernatorial candidates to raise money and have it matched anywhere in the state, while legislative candidates would only match contributions from within a district,” Malbin said. “What they were doing was to give candidates and supporting organizations an incentive to base campaigns on local organizations and local networks. I predict this will have the effect of drawing out and helping to support more candidates with more diverse political networks.”

According to CFI’s analysis, Senate candidates participating in the program would see their share of small-donor contributions of $250 or under rise to 45 percent of their total campaign funding, or up to 56 percent if the number of small donors increases, with non-party organizations like PACs and LLCs falling from 45 percent as of 2018 to around 28 percent of contributions. Assembly candidates would see small donors and matched money become 62% of their total funding, or up to 73 percent if more small donors are incentivized to give, with PACs and LLCs falling from 44 percent as of 2018 to around 23 percent.

“Public resources focused on in-district donors and combined with only contributions of maximum $250 that will be matched, it’s multiplying the potential change that can come out of this program,” Malbin said.

Suddenly coffee klatches in a neighbor’s living room can be lucrative, and the candidate who does not want to rely on major donors has a way of energizing local donors that is not based on national web-based tools.

Michael J. Malbin, Executive Director, Campaign Finance Institute

The CFI study concludes that even just taking into account contributions from 2018 donors, nearly all candidates would be better off with the public matching funds, and that participation is likely to grow. “With new donors, the average challenger, incumbent, and open-seat candidate all would have come out ahead in both chambers under the tiered match,” the report found. Malbin highlights one other intriguing finding of the effects of offering a public matching option for donations under $250: in every district, there is likely to be a contested election.

“It’s an unprecedented package of innovations, refocusing the campaign finance debate on what is the purpose of representation,” Malbin said. “Instead of a single-minded focus on getting big money out, it’s asking what should representatives be doing, and it’s saying that as a public policy we want to reinforce the role of public officials as representing their geographic constituents.”

Jessica Wisneski, co-executive director of Citizen Action of New York, told Sludge that she thinks the system will help New Yorkers achieve reforms on big issues they care about.

“Every single issue the people are fighting for—from police accountability to health care for all—are opposed by deep-pocketed special interests who use campaign cash as a weapon against transformational reforms,” Wisneski said. “Public financing shifts power from corporate interests to everyday people. It’s the foundation for the big changes everyone is hungry for, and it’s why we have to push hard to implement the new system in New York State and insist that it be ready for the 2024 election cycle.”

The New York primary election is on Tuesday, June 23. For early voting information, voters statewide are instructed to contact their county Board of Election. In New York City, early voting locations are available through June 21. Previously-requested New York absentee ballots must be postmarked by June 23 or hand delivered to a BOE office by close of polls on June 23, as instructed by the New York state Board of Elections.