Around this week’s Democratic debate, pundits savored a juicy term that crystallized the candidates’ differences on campaign finance: “wine cave,” a reference to the site of Pete Buttigieg’s recent high-dollar fundraiser. (Post-debate, many pundits feigned that they didn’t quite know and couldn’t seem to figure out what a Napa wine cave was, which seems a bit rich.)

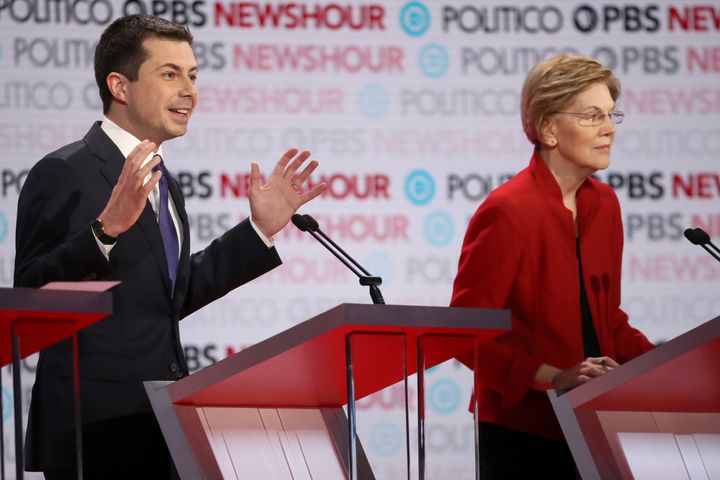

Onstage, Elizabeth Warren contrasted the special access Mayor Pete’s wealthy donors get to the winding free-selfies lines at her rallies. Bernie Sanders has similarly drawn contrast between his vast grassroots support and Joe Biden’s corporate backers and allied super PAC. Neither Sanders or Warren have bundler programs or hold closed-door, high-dollar fundraisers.

Buttigieg’s response was a version of “hate the game, not the player,” a defense often used by corporate-funded candidates. “If I pledge never to be in the company of a progressive Democratic donor, I couldn’t be up here,” Buttigieg said on stage. This response, probably intentionally, conflates several issues of corrupting influence and campaign finance practices that deserve closer examination.

Corporate executives and lobbyists can bundle maximum contributions of $2,800 to candidates that don’t disavow their help, quickly raising at least tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars during a primary, often from colleagues whose industries spend millions of dollars on lobbying the office the candidate is seeking.

For candidates that receive a lot of wealthy-donor support, a backer might respond, “Do high-dollar bundlers really get improper influence over legislation and public policy from these early contributions?”

The answer is clearly yes, according to experts in the money-in-politics field. Dozens of academic studies published over the past ten years establish the correlation of politicians’ fundraising abilities and special-interest influence over policy. Additionally, the firsthand testimony of former (or current) elected officials, lobbyists, watchdogs, and consultants attests to the causation of legalized bribery.

One current case study is the No Fossil Fuel Money Pledge, a voluntary commitment taken by candidates to not accept more than $200 from any PAC, executive or lobbyist in the fossil fuel industry. With their combined experience and national membership, the 17+ environmental groups behind the pledge have identified large executive and lobbyist donations as an area of focus, publicly acknowledging the need to limit the contributions to achieve strong climate action in the face of a catastrophic global crisis.

The pledge is designed to work as a clear signal of climate policy independence—after all, large donations from non-executives or non-lobbyists in the fossil fuel industry would still technically be permitted. As a hook for continual public accountability, it works to counteract the over $1 billion spent by just five Big Oil companies on lobbying and ads since the 2015 Paris Agreement, and the pervasive influence of the fossil fuel industry against necessary climate policy.

Earlier this year, Leah Stokes, an assistant professor of political science at the University of California, Santa Barbara, found that 45% of senior congressional staff admit to changing their mind about a policy after meeting with a contributor. Stokes also drew attention, from her research in climate policymaking, to the findings of a 2015 study that senior policy makers were three-to-four times more likely to meet with a campaign contributor.

Buttigieg signed the pledge, as did 13 other major Democratic presidential candidates, but Mayor Pete continued to accept bundled donations from “shadow lobbyists” for the fossil fuel industry. The Buttigieg campaign held high-dollar fundraisers from hosts with extensive oil and gas industry financial interests, such as Hamilton James, an executive with private equity giant Blackstone. After committing in April to transparency around his bundler programs and fundraiser events, the Buttigieg campaign revoked press access in October and November, before reversing course earlier this month and releasing a hastily-updated bundler list of donors raising over $25,000. One bundler turned out to be a natural gas lead at the McKinsey consulting firm, which No Fossil Fuel Money Pledge organizers described as skirting the spirit of the pledge in ways that just this week resulted in public warnings for the Biden campaign.

The Buttigieg campaign’s dance around the No Fossil Fuel Money Pledge is reminiscent of a public debate last year surrounding Beto O’Rourke’s 2018 U.S. Senate run. Around this time last year, Sludge’s investigative reporting resulted in Beto being dropped as an individual signer of pledge for his Senate campaign taking dozens of donations over $200 from oil and gas executives and not choosing to return them. Alex Kotch’s reporting last year prompted a news cycle of examination on the nature of fossil fuel industry influence, campaign finance, and the corruption of climate policy as the climate crisis deepens.

Months of public questions followed from climate activists such as the Sunrise Movement and students at the College of William & Mary, who prompted O’Rourke to publicly invoke versions of the “anyone’s money is welcome” line, much as Mayor Pete has. (Meanwhile, Beto’s presidential campaign refused to respond to press inquiries from Sludge, much like Buttigieg’s has.) Eventually, on May 1, Beto re-signed the pledge as a presidential candidate, with a video in which he said his decision was “in large part because I was asked to” by activists, and that he was now seeking to avoid “any real or perceived conflicts of interest.”

Two academic studies published in the last two years advance knowledge of how campaign contributions, especially from well-connected lobbyists, can lead to later legislative access and preferential policy outcomes.

“What do campaign contributions buy? Lobbyists’ strategic giving”—Amy McKay, March 2018

McKay’s research focused on personal contributions from registered lobbyists, an under-explored data set, and concluded that lobbyists strategically increase and decrease their giving to senators on key committees overseeing their industry throughout the legislative process.

“Lobbyists who donate to legislators are doing so for transactional reasons—to influence legislative decision making, not to influence electoral outcomes,” McKay writes. “If so, lobbyists strategically contribute to the legislators with the most power over their issue area, and they time these contributions to have maximum effect.”

To test her theory, McKay examined lobbyists’ contributions around the 2008-2010 health care debate. She found that lobbyists working on health issues gave more money to senators during the period than lobbyists working on non-health issues, and that their average contribution amount was higher as well. In addition, the health lobbyists’ donations were more consistently directed to members of the committees working on health care legislation during that period than at other times.

“How Do Interest Groups Seek Access to Committees?”—Alexander Fouirnaies and Andrew B. Hall, Feb. 2017

Fouirnaies and Hall’s approach examined a new dataset of over 440,000 observations from U.S. state legislation combined with campaign finance data from 1988 to 2014. Starting by noting that direct campaign contributions from corporations are relatively small in the overall economic landscape, the authors examined donors’ strategies by comparing differences in committee roles of their recipients and found that “interest groups seek out the committees with policy jurisdiction over their business interests.”

What’s more, the analysis shows that the power to appoint committee roles is highly sought after. They quote a 2016 study’s findings: “When legislators are appointed to high-profile committees they not only gain the ability to exert broad influence on legislation, they also signal to PACs that the legislator is an effective and respected member of Congress.” They conclude, on the value of committee assignments, “because these decisions occur early in the session and are removed from policy decisions, they are likely to be less visible to the public.”

Money-in-politics researchers have established evidence that fundraising prowess leads to key committee assignments, and in turn that committee chairs exert power over what’s legislatively possible through setting and limiting the agenda. In 2008’s “Sharing the Wealth: Member Contributions and the Exchange Theory of Party Influence in the U.S. House of Representatives,” Damon M. Cann, assistant professor of political science at the University of Georgia, found that intra-party fundraising largesse influences chair assignments to House committees and key appropriations subcommittees. In this way, early bundled donations in the tens and hundreds of thousands of dollars leads the way for later industry PAC spending in the millions—and around elections, “dark money” group spending in the tens of millions. A May 2019 study’s summary reports finding a top-tier of 100 well-connected organizations—out of 37,706 lobbying between 1998 and 2012—that account for one-third of all lobbying spending.

The influence of Big Money and lobbyists over the legislative process has been troublesome enough to prompt 14 U.S. state governments to adopt some form of public financing of elections. More municipalities are experimenting on increasing voter turnout and participation—and mitigating the influence of deep-pocketed interests such as the real estate industry—with innovations such as public matching funds, democracy vouchers, and ranked-choice voting.

Among the 2020 Democratic hopefuls, Buttigieg stands sixth overall in share of small-dollar donations among total raised, with just under 48 percent. Sanders is third, with over 58 percent, and Warren is fourth, at a bit over 53 percent, according to the Center for Responsive Politics. Biden comes in eighth, with just 36 percent, his small-donor haul of $13.2 million amounting to 54 percent of Buttigieg’s, about 41 percent of Warren’s, and under one-third of Sanders’.

A Sludge and Data For Progress analysis of donor demographics from the first half of this year found that Buttigieg has received contributions from more individuals who earn above $100,000 per year than any other candidate (4,832). According to this analysis of donors giving over $200, Sanders received the smallest share of campaign funding from earners above $100,000, with 43 percent. Warren received the second-least at 47 percent, compared with Buttigieg’s 62 percent and Biden’s 66 percent.

So, is it an unethical project—corrupt, even—to run a campaign that’s more than half or two-thirds reliant on wealthy donors, with stacks of checks called-in from bundlers whose industries contract with high-powered lobbyists? The argument from some of the status quo’s defenders is no—that Buttigieg might be running his campaign on $250,000 gifts bundled from corporate lawyers, but that Mayor Pete possesses the strength of character to not reward those lawyers’ wealthy clients with legislative access and valuable policy outcomes when in office. A typical social-media tussle might proceed as, “Actually, it’s tactically savvy for my candidate to power their presidential campaign with millions from max’d-out private equity vultures. My candidate is uniquely equipped to act as a special agent of change in the influence machine, you’ll see.” One initial response is that 2009’s Fair Elections Now Act, the main vehicle to establish a public matching funds system for federal elections, never made it out of the House subcommittee where it was assigned in a Democratically-controlled Congress.

Or self-described campaign-finance realists sometimes admit bundling to be unethical, but describe it as a necessary compromise for Democrats to compete with deep-pocketed Republicans. A commonly-expressed sentiment from some supporters of Biden or Buttigieg (or, previously, O’Rourke) is that all donations to Democrats are welcome—even from fossil fuel industry executives, the people most heavily invested in the status quo of destroying the Earth’s habitability over the next century—in order to battle President Trump and the GOP’s corporate-stuffed war chest. If this argument in the primary is being made to infrequent general-election voters, its ostensible advantages would have to be weighed against the observable costs of captured public policymaking, historically low trust in government, and generally low voter turnout in representative democracy. As Columbia Law Professor Tim Wu described the republic’s frustrated landscape earlier this year, “Entire categories of public policy options are effectively off-limits because of the combined influence of industry groups and donor interests.”

The findings of these academic studies, combined with the decades of experience of good government groups and campaign finance reformers, stand ready to review from money-in-politics experts. Large campaign contributions do work to ensure special access and influence, priming the pump for the enormous lobbying expenses and rich compensation through the revolving door (the main “cash-out” event for senior staff and politicians). A candidate’s reliance on bundling from lobbying interests results in special access, diminished policy outcomes, and an inability to address the climate crisis and other issues—what political scientists have described as systemic, or institutional, corruption.