This 2019 piece was by Brendan Fischer, director of Campaign Legal Center's Federal Reform Program.

Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s long-awaited report into foreign interference in the 2016 presidential election exposed vulnerabilities in our campaign finance system that extend beyond Russia. Neither foreign governments nor domestic billionaires are going to stop looking for ways to influence U.S. politics, and it is about time that the Federal Election Commission (FEC) and Congress step up.

So what does the report tell us about our campaign finance laws, and how can these issues be addressed to protect the integrity of our elections?

Campaign finance law has a major digital disclosure gap.

Mueller’s report confirms what we mostly already knew: U.S. campaign finance law has a digital disclosure gap. Russia exploited that gap in 2016, but Congress and the FEC still have not closed it.

One prong of Russia’s election meddling effort involved a social media campaign “designed to provoke and amplify political and social discord in the United States,” Mueller’s report states. This included spending at least $100,000 on Facebook ads, many of which, according to Mueller, “explicitly supported or opposed a presidential candidate.”

Russia, of course, never disclosed its political ad spending to the FEC, and didn’t include on-ad disclaimers stating “paid for by Putin”—but it was largely not required to do so, and neither were any other similar digital advertisers.

Had effective online disclaimer and disclosure laws been in place in 2016, Russia’s wide-ranging influence campaign might have been detected sooner—or Russia might have been deterred from engaging in the effort in the first place. And voters would have had a lot more information about the domestic interests trying to sway their votes, too.

Under current law, outside groups only have to report spending on digital ads when they expressly advocate for or against candidates. Most of Russia’s ads didn’t meet that standard. Even those ads that Mueller characterized as “overtly oppos[ing] the Clinton Campaign”—like one that pictured Clinton and read “If one day God lets this liar enter the White House as a president, that day would be a real national tragedy”—may not be considered express advocacy by the FEC.

If ads like this one had been run on TV, however, they would have been subject to legal disclosure requirements because they would have qualified as “electioneering communications.” Electioneering communications are currently defined by the FEC as broadcast—but not digital —ads run near an election that name a candidate, and are targeted to that candidate’s voters, even if they don’t expressly tell viewers to vote for or against a candidate.

Russia was not alone in exploiting these digital ad disclosure loopholes. According to a peer-reviewed study by University of Wisconsin-Madison Professor Young Mie Kim, 25 percent of Facebook political ads that ran in the final weeks of the 2016 election mentioned candidates and would have been subject to disclosure as electioneering communications if aired on TV.

Congress and the FEC failed to close these loopholes in the wake of 2016, so our system maintained the same vulnerabilities going into the 2018 midterms. And, indeed, groups looked for new ways to exploit them: Campaign Legal Center identified that the Democratic dark money group Majority Forward ran an online ad campaign targeted at voters in states with competitive Senate seats, but did so without reporting that spending to the FEC and without telling viewers that the ads were paid for by Majority Forward.

Moreover, thanks to past efforts by Facebook, the FEC has largely exempted digital political ads from on-ad “paid for by” disclaimers. This meant that voters couldn’t tell the difference between an ad paid for by a foreign government and an ad paid for by a domestic dark money group. Both were similarly shrouded in secrecy.

Unfortunately, this problem is only going to get worse. Political spending is increasingly migrating online: in 2018, digital political spending hit $1.8 billion, or 20 percent of total ad spending—an astonishing 2,400 percent increase as compared to the 2014 midterms, according to Borrell Associates. Facebook has begun to institute some new disclaimer requirements, but enforcement has been haphazard, and Facebook’s self-regulatory efforts don’t apply to other platforms.

The good news is that there are relatively easy fixes to these problems.

Congress should extend the definition of electioneering communications to paid digital ads so that ads like Russia’s are subject to the same disclosure and disclaimers that currently apply to political ads run on TV or radio. This fix is included in bipartisan legislation like the Political Accountability and Transparency Act (H.R. 679) and the Honest Ads Act, and it is also in the For the People Act (H.R. 1). The FEC should also clarify that “paid for by” disclaimers are required on digital ads. It has been sitting on proposed regulations since 2011 and held a hearing on digital disclaimers last year, but it has yet to finalize any rules.

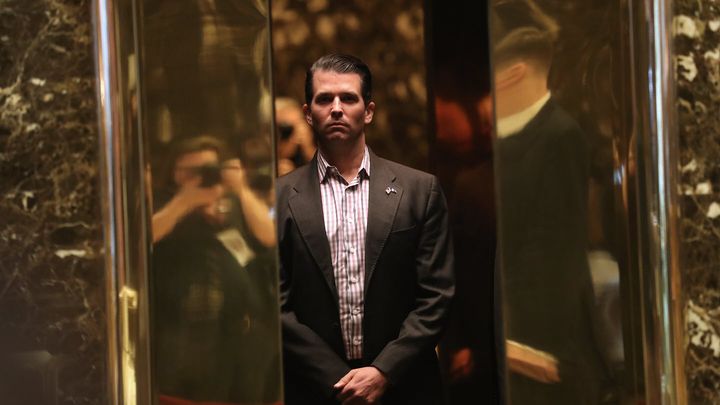

Don Jr. isn’t going to jail, but he could still face civil enforcement action by the FEC.

Mueller declined to criminally prosecute the president’s son, Donald Trump, Jr., in connection with the June 2016 Trump Tower meeting where, according to the report, he met with a “Russian government attorney” to accept “official documents and information that would incriminate Hillary.”

But Don Jr. isn’t in the clear just yet.

Mueller acknowledged that Don Jr. setting up a meeting to accept “high level and sensitive” opposition research from a foreign government, presented as “part of Russia and its government’s support for Mr. Trump,” could violate the prohibition on soliciting a contribution of “anything of value” from a person he knew was a foreign national.

Citing FEC guidance, Mueller largely concluded that opposition research should be treated as a “thing of value” subject to the foreign national contribution ban (although he acknowledged that courts have not squarely addressed the issue). This shouldn’t be too surprising: campaigns and PACs spend tens of millions of dollars every election cycle researching their opponents in order to gain an electoral advantage. And, as Mueller noted, a “foreign entity that engaged in such research and provided resulting information to a campaign could exert a greater effect on an election, and a greater tendency to ingratiate the donor to the candidate, than a gift of money or tangible things of value.”

Think about it—if opposition research was not a contribution for purposes of the foreign national ban, then we’d be handing an enormous amount of power to foreign governments to legally meddle in U.S. elections. A foreign intelligence service could target every potential U.S. candidate and dig up incriminating details,or even lure them into compromising scenarios. The foreign government then could choose which candidates they want to support and provide those candidates dirt on their opponents–and it would be entirely legal.

The main reason Don Jr. wasn’t charged, however, is that Mueller couldn’t establish that he “acted ‘willfully,’ i.e. with general knowledge of the illegality of [his] conduct.” Mueller couldn’t prove that the president’s adult son knew that taking dirt on a political opponent from a foreign government was illegal.

As Rick Hasen noted, Don Jr. “declined to be voluntarily interviewed” about the meeting, and we don’t know whether Mueller could have established Don Jr.’s “willfulness” if he had been called before the grand jury.

The FEC, however, won’t face the same challenges in pursuing civil penalties.

For a criminal campaign finance violation, prosecutors must show that it was committed “willfully.” There is no “willful” requirement for civil enforcement by the FEC, which need only find reason to believe that Don Jr. solicited a contribution from a person he knew was a foreign national. That evidence is in Mueller’s report, and the law is on the FEC’s side.

Campaign Legal Center, along with Common Cause and Democracy 21, filed a complaint with the FEC about the Trump Tower meeting in July 2017. That complaint is still pending.

The Mueller report underscored our system’s still-open vulnerabilities to foreign interference online, and it also highlighted already-available tools the FEC has to enforce existing law. It is now up to the FEC and Congress to take the next steps.

The FEC and Congress should close the digital loopholes that Russia successfully and extensively exploited in 2016, and the FEC should use its civil enforcement authority to enforce the foreign national ban.

This 2019 piece was by Brendan Fischer, director of Campaign Legal Center's Federal Reform Program.

Related: