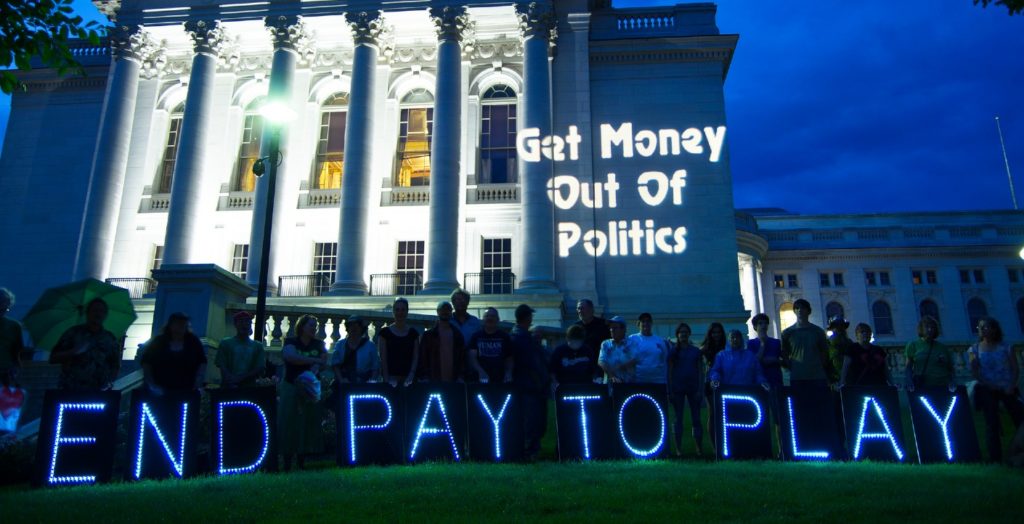

As Sludge follows the money in the political system, here are some of the reforms that good government and community groups are advancing for a stronger, most trustworthy, and more inclusive democracy.

First, here are some quick facts on the current health of U.S. democracy:

- Just 55.7% of the voting age population turned out in the 2016 presidential election, placing the U.S. 26th out of 32 countries in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

- But, while voter turnout in the 2014 midterm elections was only 41.9%, the lowest rate in any federal general election since 1942, 53.4% of voters cast a ballot in the 2018 midterms, a historic high in recent history.

- A March 2018 survey found that 77% of Americans say there should be limits on the amount of money individuals and organizations can spend on political campaigns, including 71% of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents. Only 20% of adults favor the current system of unlimited spending made possible by lax campaign finance laws.

In states and cities nationwide, however, advocates for a stronger U.S. democracy are developing legislative and policy reforms aimed to increase the responsiveness of government, for greater public accountability.

Dark Money and Donor Disclosure

Currently, organizations can spend money on elections through “dark money” non-profit groups that are not required to disclose their sources of funding, or through PACs that receive significant funding from such non-disclosing groups. Often, such dark money spending can result in inflammatory or misleading advertisements, and voters have no way to know the source of the funding behind the communication.

A 2019 poll by the nonpartisan Campaign Legal Center found that 83% of voters across partisan and demographic lines support publicly disclosing political contributions to organizations. What’s more, state governments can strengthen their disclosure laws to require that groups spending on elections list their major sources of funding, for voters to know the source of the messages on their airwaves and in their mailboxes.

More info on how dark money currently operates—and can beneficially addressed by state lawmakers—can be found on CLC’s website: StopSecretSpending.org.

Democracy Vouchers

In November 2017, the city of Seattle conducted its first elections using an innovative form of public financing that provided four $25 vouchers to every registered voter that voters could, in turn, assign to the candidate(s) of their choice. A 2018 study found that the program dramatically increased the amount of donors and their representativeness of the city’s population in terms of income, race, and age. More info at the Brennan Center, with background at Common Cause.

Stock Ownership

A review by the non-profit Campaign Legal Center (CLC) in April 2020 found that members of Congress on both sides of the aisle traded stocks as the coronavirus pandemic deepened, in the weeks before legislative relief packages. CLC found that 12 senators made 227 stock purchases or sales worth as much as $98 million, and 37 House members made 1,358 trades worth as much as $60 million. The ethics experts argue that Congress should go further and bar members of the House and Senate from trading individual stocks (but not necessarily outlaw their ownership) by passing the Ban Conflicted Trading Act. More info about congressional ethics can be found on CLC’s website.

Public Matching Funds

This method of making elections more fair and curbing the influence of special interests is in place across at least 27 states, counties, and municipalities, many of them for decades. In leading areas like New York City and Long Beach, CA, these programs have been proven to be successful in diversifying the donor base of candidates in terms of class and race. What’s more, public matching systems have also succeeded in diversifying the gender, racial, and class makeup of candidate pools.

Typically, a public matching funds system works like this, as described by the non-partisan policy institute Brennan Center for Justice: constituents who give small amounts to participating candidates will see their contributions matched by public money, often around 6-1. As a result, a constituent’s donation of $10 would be worth $70 to a participating candidate, and $175 would be worth $1,225. Candidates opt in by raising enough small initial donations to qualify, and they accept conditions including lower contribution limits.

A major 2010 study by the Brennan Center of New York City’s public matching system found: “Since the enactment of the multiple match in 2001, City elections have seen not just more donors, but more small donors. Participating candidates rely on more small donors than their nonparticipating counterparts. This has enabled candidates to fuse their fundraising and voter outreach strategies, fostering early and continuing interactions between candidates and voters.”

Common Cause’s Money in Politics & Ethics Program says that Connecticut politicians have attributed better policy outcomes in the state to its program of voluntary grants to participating, qualifying candidates. More info on small-donor matching funded election can be found at Common Cause New York, where New York City voters in 2018 overwhelmingly approved an expansion of the program, and where a statewide public match is set to be implemented after the 2022 elections.

Congressional Reform

Two-thirds of adults think other Americans have little or no confidence in the federal government, a survey taken after the 2018 election found, and that 64% say that low trust in the federal government makes it harder to solve many of the country’s problems.

To restore public trust in the federal government, nonpartisan ethics groups are focused on strengthening the independent Office of Congressional Ethics (OCE), formed in 2007 to monitor the conduct of House members and blow the whistle on conflicts of interest. Groups like Common Cause and Campaign Legal Center are also holding the Executive branch accountable on issues like the Domestic and Federal emoluments clauses, which bar the president from accepting things of value, and in watchdogging ethics violations.

Voluntary Campaign Finance Pledges

The No Fossil Fuel Money pledge is an example of how candidates and elected officials can demonstrate their commitment to independence: by pledging that their campaigns will not accept contributions over $200 from oil, gas, and coal industry executives, lobbyists, and PACs. Over 2,500 politicians all over the country — and at all levels of government — have signed the pledge, including over 50 sitting members of Congress (10+ senators; 40+ representatives) and more than 250 state elected officials.

Another example is the No Corporate PAC money pledge, which as the Campaign Legal Center has explained, does not always mean that Big Money interests are not supporting a candidate’s campaign through other donation channels and independent expenditures.

Gerrymandering and Fair Representation

Currently, in many states and cities, district lines are drawn by powerful incumbent politicians and political insiders. To ensure that districts are representative of the population, Common Cause recommends that nonpartisan Citizen Redistricting Commissions should be established to replace the current congressional and state legislative redistricting processes, and that fair criteria for drawing districts should be clearly laid out—for example, ensuring compliance with The Voting Rights Act

(VRA). With public participation and transparency, voters can fairly choose their politicians, as opposed to the other way around.

Coming soon: more informational resources on Democracy topics such as election security, the security of vote-by-mail, and more state news. For questions or feedback, please contact the Sludge editors here.