The chair and the ranking member of the Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works floated draft legislation in late June on the “forever chemicals” known as PFAS that critics argue would fail to regulate the toxic substances by implementing a restrictive legal definition of the compounds that is more aligned with chemical industry interests than the public health. Notably, the two senators who drafted the legislation are among the Senate’s top recipients of chemical industry donations.

The new draft bill is a recent development in a years-long fight over PFAS policy that comes as the chemical industry is spending more money than ever to lobby the federal government. The bill follows the 2021 bipartisan PFAS Action Act, which passed the House but died in the Senate Environment and Public Works (EPW) Committee after a blitz of chemical industry lobbying.

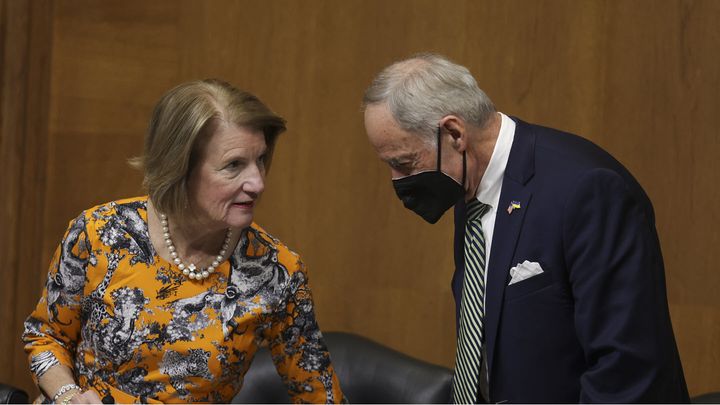

Ranking member Sen. Shelley Moore Capito (R-W.V.) did not support the 2021 legislation, which would have been far more comprehensive than the new Senate draft bill, citing the views of “local stakeholders” and the “uncertainty and unintended consequences” of the policy proposal. Since then, EPW Chairman Sen. Tom Carper (D-Del.) has repeatedly pledged to put forward bipartisan PFAS legislation, which has now manifested in the long-anticipated draft bill.

PFAS, an acronym for perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances, are known as “forever chemicals” because they do not naturally break down and are highly mobile, having been found in tap water across the country and in the blood of 97% of Americans. Studies have repeatedly linked PFAS to adverse health effects including ulcerative colitis, thyroid disease, decreased fertility, damage to the immune system and increased risk of cancer. The public health crisis posed by the chemicals has gained wider recognition in recent years after lawsuits revealed that top PFAS-producing companies knew about the dangers of the compounds for decades but concealed them from the public.

Prominent environmental groups including Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility (PEER) and the National Resources Defense Council (NRDC) have called out Carper and Capito for defining PFAS chemicals too narrowly in their proposal. PEER argues that the bill’s “weak” and “vague” definition would exclude many toxins from regulation and undermine national and state efforts to address PFAS, while the NRDC wrote that the draft bill’s definition “undermines the credibility of the entire product.”

In letters sent earlier this year, the environmentalist groups urged the senators to define PFAS substances in their bill as chemicals with “one fully fluorinated carbon atom,” as opposed to the “at least two fluorinated carbon atoms” required by the current draft proposal. PEER noted in its letter that major bodies such as the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, the European Union, United States Geological Survey, and 18 states such as California, Washington, Maine, Maryland, and New York use the “one fully fluorinated carbon atom” definition. Over 14,000 chemicals could be considered PFAS under the broad definition sought by the environmental groups, versus around 6,500 substances under the narrow definition sought by the chemical industry and included in the draft bill, according to PEER’s Science Policy Director Kyla Bennett, who was formerly an attorney with the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

PEER and the NRDC also take issue with the draft bill’s reliance on voluntary programs, which they argue would allow the chemical industry to regulate itself. The groups note that previous voluntary programs put forward by regulators led to one toxic chemical being replaced by a substance that is similarly toxic or even more dangerous, a phenomenon that in the toxic substance control arena is called “regrettable substitution.” For example, the EPA’s 2006 voluntary agreement with DuPont regarding chemicals known as PFOA led to the company replacing the chemical with GenX, a substance the EPA later found to be potentially even more toxic than its precursor. While the EPA recognized PFOA as toxic with a non-enforceable drinking water advisory level for years, the agency did not enact a similar health advisory for GenX until 2022, enabling the proliferation of the new toxin in areas like the Cape Fear River.

“I firmly believe that industry is now willing to give up [the PFAS chemicals] PFOA and PFOS as sacrificial lambs, so long as they can keep using their regrettable substitutions,” Bennett told Sludge. “They are always trying to say that there are ‘bad’ PFAS and ‘safe’ PFAS. Make no mistake—there is no safe PFAS.”

Bennet said that regulations should define PFAS broadly, regulate them as a class, and ban all non-essential uses, and that she believes any exclusions in the law would be fully taken advantage of by the chemicals’ manufacturers.

The chemical industry has repeatedly voiced its opposition to broad PFAS definitions that would regulate the substances as a class. “The most problematic pieces of legislation include inappropriate and overly broad definitions of PFAS that pull in many potentially unintended substances and products,” the American Chemistry Council’s senior director of product communications Tom Flanagin told the Washington Post last year. Since the draft bill was released in late June, the American Chemistry Council (ACC) has published blog posts warning that the broader, single-fluorinated carbon definition would hurt climate change and healthcare outcomes.

Sludge spoke to a number of ACC representatives who did not confirm whether or not the Council was involved with creating the draft bill, or if they had lobbied the senators for the narrow PFAS definition. Sludge also contacted a number of Senate EPW staffers who refused to comment on chemical industry involvement in the bill. The American Chemistry Council’s lobbying disclosures for the first two quarters of the year say that it lobbied Congress on “Unintroduced PFAS legislation.”