State supreme courts were thrust into the spotlight this year, first through lawsuits around how governments could respond to the coronavirus emergency, and then through legal tussles over how citizens could safely vote in a pandemic election. While state supreme courts typically rule on appeals in civil and criminal cases, this year in states like Texas the courts were issuing highly consequential and high-profile rulings on vote-by-mail access and early vote locations just weeks before Election Day.

The past few judicial election cycles determined the makeup of state courts that will decide cases arising from redistricting processes after the completion of the 2020 Census, with implications for partisan gerrymandering that could potentially last for a decade.

Over the past decade, state judicial races have ramped up from low-dollar affairs into multi-million-dollar TV battles. Over a half billion dollars has been spent on the races since 2000, according to a report last year from the Brennan Center for Justice, a non-partisan policy institute.

Voters can testify they’ve been seeing increasing—and increasingly negative—TV ads for state court races. But voters are often kept in the dark about who’s behind the fear-mongering ads. In the 2018 election cycle, almost $40 million was spent on close to 50 state court races in 21 states, with a hefty 27% coming from groups that keep their funders’ identities secret, the Brennan Center found.

This anonymous cash has fueled a sharp rise in negative ads, often accusing justices of being “soft on crime.” Outside spending groups in state court races were responsible for two-thirds of the negative ads on the air, despite only paying for one-third of all ads, according to the Brennan Center.

Research clearly shows that these ads pressure judges into changing their behavior in election years, issuing harsher rulings in criminal cases in order to avoid the next attack ad.

Douglas Keith, Brennan Center for Justice

This year, a number of states felt the brunt of dark money spending as hard-to-identify PACs funded by “dark money” nonprofits spent millions of dollars to shape state courts. These PACs are known as “gray money” spenders, because while they technically disclose their donors to state officials, their donors include groups that are non-transparent, in whole or in part. What’s more, PACs with ambiguous names like Justice for All often don’t have websites, so it’s difficult for viewers to find basic information about who they are and what their mission is.

One the largest gray money group outlays was in Texas, where the Judicial Fairness PAC spent an estimated $2.1 million on TV ads defending the all-Republican Texas Supreme Court. As Sludge previously reported in the run-up to Election Day, Judicial Fairness PAC lacks a public website, meaning that voters could not easily look up information about who was running the ads they were seeing.

The shadowy Judicial Fairness PAC shares a treasurer with one of its major donors, a state group called Engage Texas that’s funded by an affiliated federal super PAC of the same name, and received millions more from an influential tort reform organization connected to state Republican megadonors. The four Republican justices up for reelection this cycle each won with slight majorities of the vote, dashing Democratic hopes of a pickup.

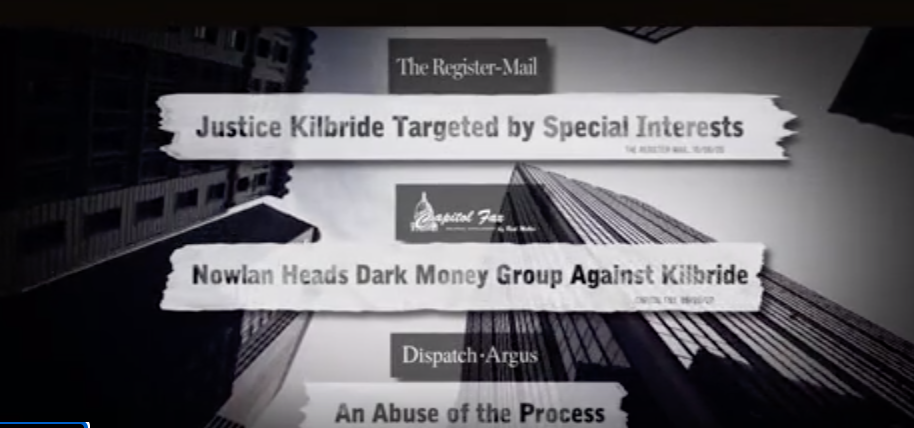

Another sizable gray money victory happened in Illinois, where Citizens for Judicial Fairness PAC spent an estimated $2.2 million on ads attacking incumbent state Supreme Court Justice Thomas Kilbride, who needed to receive 60% of the vote of the state’s 3rd Judicial District in his retention contest. The PAC received $200,000 in September from the dark money group Judicial Fairness Project, which shares the address of the general counsel to the Illinois Republican Party. The PAC’s two TV ads linked Justice Kilbride to Democratic House Speaker Mike Madigan, saying, “Madigan’s machine funded Kilbride’s campaign with millions…”.

Kilbride earned 55.3% of the vote, shy of the 60% needed, and conceded defeat, becoming the first incumbent Illinois justice to lose a retention bid.

“The nature of state Supreme Court elections today, some judicial elections can be pretty quiet,” Brennan Center counsel Douglas Keith told Sludge, “but in the handful of states where they’ve been politicized, when large outside interest groups see a reason to get involved they can absolutely swamp what candidates themselves are spending.”

In 2018 court elections in Arkansas and West Virginia, for example, outside groups accounted for two-thirds of the money in the race.

Another major gray money group in state court contests has been the Republican State Leadership Committee (RSLC), the state campaign arm of the national GOP that is funded by the dark money U.S. Chamber of Commerce, corporations and trade associations, and the dark money Judicial Crisis Network, a shadowy national nonprofit that’s shaped communications supporting President Trump’s conservative Supreme Court nominees.

Last cycle, RSLC’s biggest benefactors included tobacco corporation Altria Group, the companies of Republican megadonors Shedlon and Miriam Adelson, pharmaceutical industry trade group PhRMA, Blue Cross/Blue Shield, and Koch Industries, a manufacturing conglomerate with oil, gas, and coal holdings.

A Sludge review of IRS douments in June found that other RSLC contributors in the first quarter of this year included Marathon Oil Company ($100,000), American Fuel and Petrochemical Manufacturers ($75,000), Peabody Energy ($25,000), Facebook ($50,000), CoreCivic ($50,000), and Pfizer ($200,000).

In the April election for the Wisconsin Supreme Court, RSLC put an estimated $280,000 on the airwaves to defend incumbent Justice Daniel Kelly out of its at least $840,000 in total spending on the race. His challenger, Dane County Circuit Judge Jill Karofsky, who was helped by non-disclosing spending from the group A Better Wisconsin Together Political Fund, won a ten-year term with 53% of the vote.

In the June 9 election for West Virginia Supreme Court, the RSLC’s Judicial Fairness Initiative spent close to $1.9 million to back incumbent Supreme Court Chief Justice Tim Armstead in the state’s First District. ReSet West Virginia PAC, an independent expenditure committee funded primarily by a dark money nonprofit called For West Virginia’s Future, spent nearly $900,000 on ads and mailers. Justice Armstead won another twelve-year term in the three-way race with the plurality of 40.9% of the vote.

In the Ohio Supreme Court election this month, the RSLC was estimated to spend nearly $300,000 on TV ads supporting two incumbent Republican Justices, Judith French and Sharon L. Kennedy. The latter retained her seat, while the former was unseated by former Democratic Secretary of State, Jennifer L. Brunner. In an ad, RSLC claimed that “Judge Jennifer Brunner threw out evidence against a teacher who was accused of using a hidden camera to record underage girls undressing.”

“In several states, these opaque groups ran ads epitomizing the problem with judicial elections today,” Keith said, “ads misrepresenting judges’ decisions in criminal cases and accusing them of being ‘soft on crime.’”

In Ohio, the RSLC ad said that Judge Brunner “risks our children’s safety.” In Illinois, an ad from a group called the Clean Courts Committee, which received funding in part from state law firms, asked, “What kind of judge releases child rapists?”

“Research clearly shows that these ads pressure judges into changing their behavior in election years, issuing harsher rulings in criminal cases in order to avoid the next attack ad. And the money behind the ads likely doesn’t care a bit about public safety, they just want to scare voters,” Keith said.

A Fix for Democracy – Following the Supreme Court’s 2010 decision in Citizens United, which banned limits on political spending by corporations, unions, and other groups, “dark money” has dramatically increased in state elections. To help voters understand who is funding campaigns and political ads, states can pass laws that require all groups who spend money on politics, including LLCs and nonprofits, to disclose the original source of their funding. Learn more—>

The RSLC’s top spending category this year was on media, tallied by the Center for Responsive Politics at $4.2 million, led by over $3.5 million to the vendor Revolution Media Group, a Los Angeles-based media buying firm whose president, Mike Vizvary, was formerly the VP of Marketing Communications for Guitar Center.

In the races this month for two seats on the Michigan Supreme Court, non-transparent spending supported both sides, significantly outpacing spending by the candidates themselves. The Democratic-aligned nominees, incumbent Justice Bridget Mary McCormack and attorney Elizabeth Welch, received backing in the nonpartisan election from Justice For All PAC, funded partly by dark money groups. The Republican-aligned nominees Brock Swartzle and Mary Kelly were backed by the Michigan Chamber of Commerce, which according to the nonpartisan and nonprofit Michigan Campaign Finance Network has spent through multiple PACs on election ads that skirt disclosure requirements. The Democratic-aligned candidates finished top two in the election.

In North Carolina, Chief Justice Cheri Beasley is headed to a recount against Republican Paul Newby, with Beasley down by just 406 votes in the initial count. Unusually, Newby stepped down from his own state Supreme Court seat to challenge Beasley for hers, after having expressed displeasure at not being appointed chief justice last year by Democratic Gov. Roy Cooper, and after using his dissents to inveigh against the court’s recognition of systemic racism in capital cases and other decisions.

If Beasley loses, the North Carolina Supreme Court will have a 4-3 liberal majority, as another Democratic justice, Mark Davis, lost his election by 48.8% to 51.2% to Republican former state senator Tamara Barringer.

Related coverage on Sludge:

Dark Money Pours Into West Virginia Ahead of State Supreme Court Election

Dark Money Floods in to State Elections, Revealing Cracks in Disclosure Laws

Dark Money Pours Into Wisconsin Supreme Court Race

Campaign Against ‘Dark Money’ Disclosure in Alaska Keeps Hiding Its Donors