As the first state in the nation to adopt vote-by-mail and automatic voter registration, Oregon has built a reputation for high voter turnout. In the 2016 general election, 68% of the state’s voting eligible population cast a ballot, well above the nation-wide average of 60.1%, according to data from the United States Elections Project. In the 2018 midterms, Oregon had the fourth-highest turnout among all states.

But while Oregon voters have their say at the ballot box, corporations have their say more frequently in the legislature, by keeping the state’s politicians awash in campaign cash. Oregon is one of five states that lack any limits on campaign contributions made by corporations, and one of eleven that lack any limit on individual donations to a candidate.

The result is that Oregon is number one in per capita corporate political donations and sixth overall in total corporate political donations, as highlighted last year by The Oregonian in its Polluted by Money series. “Companies and industry groups contributed $43 million to winning candidates in elections from 2008 to 2016, nearly half the money legislators raised,” investigative reporter Rob Davis wrote. “Organized labor, single-issue groups and individual donors didn’t come close.”

Heading into the November 3 election, a coalition of state groups calling itself YES for Fair and Honest Elections is putting the issue of unlimited corporate money in state politics before voters in a ballot initiative that would amend the state constitution. Their proposal, Ballot Measure 107, would authorize the state legislature and local governments to set limits on campaign contributions and spending, require greater disclosure of political spending, and require that political ads identify the people paying for them. To appear on this year’s ballot, the measure was certified by both the Oregon House of Representatives and Senate, where it passed with nearly three-quarters majorities and bipartisan support in late June 2019.

If we’re ever going to realize the full promise of this imperfect democracy, to make it truly representative and reflective of the American people, then we need to divorce power in our democracy from wealth.

Kate Titus, executive director, Common Cause Oregon

The conditions that made Ballot Measure 107 possible took over two decades to come together, as state lawmakers and money-in-politics reformers wrestled with the effects of a series of prior court rulings. A 1997 Oregon Supreme Court decision struck down campaign contribution limits that were passed in 1994, citing state constitutional protections for free expression. Then in 2006, Oregon voters passed Ballot Measure 47 by a vote of 53%-47%, which would have prohibited donations from corporations and labor unions to candidates, and would have limited donations in statewide races to $500 and in local races to $100. But its 2006 companion measure to amend the constitution, Measure 46, was rejected by voters, so the limits were not allowed to take effect.

In 2016, voters in Multnomah County, which includes the city of Portland, approved by 89% a measure to bar political contributions from corporations and limit individual donations to candidates in the county at $500. In 2018, Portland voters passed the same prohibition on corporate contributions and limits on individuals’ donations with 87% in favor, showing further support for curbing the influence of big donors.

The campaign finance landscape in Oregon changed suddenly on April 23, 2020, when the Oregon Supreme Court ruled that strict contribution limits adopted in 2016 by Multnomah County voters are legal under the state constitution. In effect, this reversed the 1997 ruling, elements of which Chief Justice Martha Walters described as “erroneous” in how they addressed protections for free expression, and put Oregon among the other 45 states that either set limits on corporate contributions or prohibit them. The April ruling, to be applied going forward, set the table for Ballot Measure 107 to shut off the spigot of unlimited donations to lawmakers from industries that lobby the statehouse.

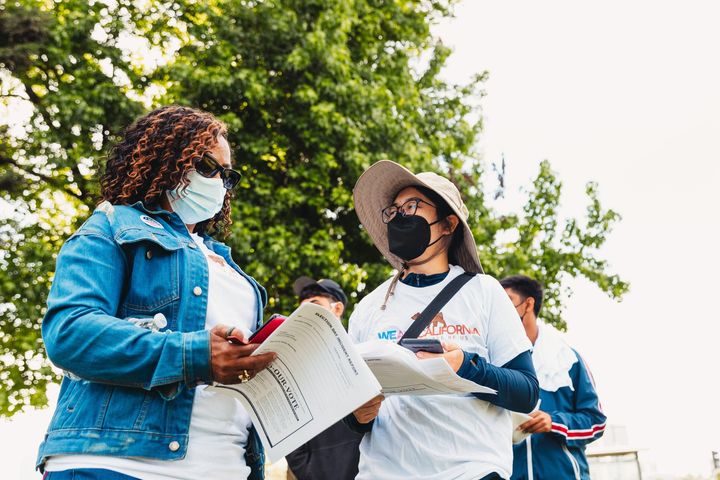

One notable aspect of this year’s Yes for Fair and Honest Elections coalition is the number of state groups behind the initiative, Kate Titus, executive director of the nonpartisan group Common Cause Oregon, told Sludge. “Grassroots advocates are championing Ballot Measure 107, with some 50 organizations and rapidly growing, from democracy groups like Honest Elections Oregon and Portland Forward, to civil rights and community groups like Unite Oregon, the Asian Pacific American Network of Oregon (APANO), and Oregon’s Farmworker Union.” Honest Elections Oregon is the coalition that led the 2016 and 2018 ballot measures, while Unite Oregon’s website describes it as “a membership organization led by people of color, immigrants and refugees, rural communities, and people experiencing poverty.”

“It really comes down to this: voters have a right to know the true source of campaign finance information and put sensible limits on the money spent to influence our votes,” Titus said. “If we’re ever going to realize the full promise of this imperfect democracy, to make it truly representative and reflective of the American people, then we need to divorce power in our democracy from wealth.”

Titus said the legislature’s vote of approval was shepherded by Democratic state Sen. Jeff Golden and Republican state Sen. Tim Knopp.

The most eye-popping donation under Oregon’s limitless contributions was the $2.5 million given in 2018 by Phil Knight, the billionaire Nike co-founder, to Republican gubernatorial candidate Knute Buehler, who was facing off against Democratic Gov. Kate Brown. Brown endorsed campaign finance limits in a March 2019 letter to the Senate Committee on Campaign Finance and has contributed in-kind support to the formation of the Yes on 107 coalition since April. In 2019 and 2020, top contributors in Oregon elections include Electrical Workers Local 48, Oregon Association of Hospitals and Health Systems, Oregon Health Care Association, and the Oregon Association of Realtors, according to data from the National Institute on Money in Politics.

Lawmakers are allowed to “double dip” by receiving per diems from their campaigns and still use campaign funds for things like swanky hotel stays, nights out at the sports bar, dry cleaning bills, and new Apple gear, the Oregonian reported.

Former Democratic Rep. Betty Komp told The Oregonian last year that the key dynamic with corporate lobbyists, enmeshed with statehouse lawmakers, was “what they thought I should be saying in our leadership meetings about whether a bill should be moving forward.” Oregon comes in last among West Coast states in a number of metrics on environmental protections, the reporting series found—for example, it stands alone in not requiring review of environmental risks before approving major construction projects. Oregon lawmakers ranked first in the average amount received from the timber industry, with $21,416, contributing to heavy industry influence and weak environmental protections around logging and endangered species.

“We’ve seen it for years around housing developers, where voters couldn’t even pass reforms to expand housing while having a huge crisis in affordable housing. Developers had passed a ban against inclusionary zoning,” Titus told Sludge. “It plays out too in everything from health care to police accountability.”

On July 30, the Yes on 107 campaign released the results of a statewide survey of likely voters by Democratic public opinion firm GBAO that found 85% support for the measure, which remained strong even after hearing negative messaging.

Titus said that a kickoff virtual house party event for the ballot campaign in July raised $10,000 from small contributions, and that the coalition will be doing public presentations through election season. “Some organizations have been working for years to educate and mobilize the public to amplify voice through collective action, holding forums around the state, being a watchdog for how this plays out in the legislature, sometimes in local government.”

In Portland, the 2020 election is the first cycle with a 6-to-1 match for participating candidates from eligible donors, and as of January seven city council candidates had qualified for the program, and mayoral candidate Sarah Iannarone. With a design based on New York City’s successful public matching system, the Portland program was picked back up by the Portland City Commission in 2016 after being narrowly repealed by 50.38% of the vote in 2010.

Portland Mayor Ted Wheeler is not opting-in to the public match, and though the city’s campaign contribution limits are now ruled to be in effect, a judge ruled in May he will be allowed to keep large donations of $25,000 from an electricians’ union and $10,000 apiece from five other influential donors including Nike, the Portland Metro Association of Realtors, and lumber company CEO Peter Stott.

If Measure 107 is approved, Titus sees opportunity for legislative action on greater transparency in election spending, such as disclosure around independent expenditures. “We’re working to build support for basic principles, going into negotiations, around reforms that build public trust and lead to more reflective representation,” Titus said.

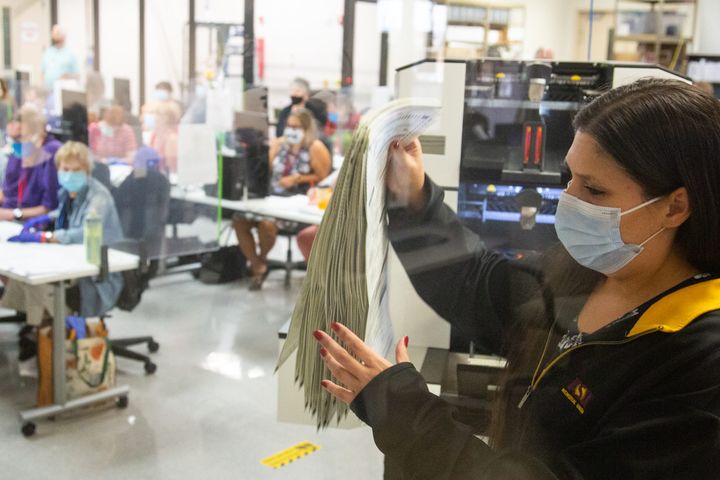

In Oregon, ballots will begin being mailed out on October 14, according to the Secretary of State’s website, when the website’s drop box locator will be updated as well.

A Fix for Democracy – Some localities, notably Seattle, have instituted a form of campaign financing that distributes vouchers citizens can donate to eligible candidates, who can then cash them in for public funds. According to a study of the vouchers in Seattle’s 2017 elections by SUNY-Stony Brook Prof. Jen Heerwig, the program diversified who funds local elections, doubling the overall donor participation rate and containing a higher share of people of color compared to cash donors. Learn more—>