The crowded Democratic congressional primary in New York’s 17th Congressional District, encompassing some of the wealthy suburbs north of New York City, was roiled over the past week by a candidate pledge around divesting from pharmaceutical industry stocks.

The pledge, signed initially by six of seven candidates in the Democratic field to replace longtime Rep. Nita Lowey, sought to ensure financial independence of the eventual nominee on issues of prescription drug affordability. As reported last week by The Journal News, the participating candidates agreed to “liquidate any direct stock holdings in pharmaceutical companies before assuming office in January of 2021.”

The one candidate who at first declined to sign was former federal prosecutor Adam Schleifer, who owns pharmaceutical company stocks worth between $26 million and $55 million, according to his financial disclosure. The candidate is the son of Dr. Leonard Schleifer, founder of pharmaceutical company Regeneron, which is based in the district. This week, Regeneron announced the start of human trials of its COVID-19 antibody cocktail, the first such tests in the nation.

The issue of pharmaceutical company holdings was raised by the other campaigns as well as by local activist groups because Schleifer is largely self-funding his bid, with more than $1.6 million loaned to his campaign, over two-thirds of its $2.3 million in funding. Schleifer’s campaign had spent $877,336 as of the end of the first quarter, led by almost $300,000 in media buys placed by high-powered consulting firm SKDKnickerbocker and close to $100,000 in direct mail, according to FEC data.

The district, which as a recent New Yorker piece about the race put it, represents “America’s quintessential rich suburbs, once a backdrop for John Cheever’s short stories,” is rated as safely Democratic by Ballotpedia—so the primary winner could hold the seat for years, as Lowey has since entering the U.S. House in 1989.

The other six candidates vying for the NY-17 nomination are as follows: four-term New York Assemblymember David Buchwald, New York Senator and former member of the Republican-aligned IDC David Carlucci, military veteran and Professor at Baruch College Asha Castleberry-Hernandez, former Obama administration defense official Evelyn Farkas, former NARAL board chair and author Allison Fine, and activist and attorney Mondaire Jones.

A new poll of the district by Data for Progress found Carlucci, who has held the region’s Senate seat since 2010, with a narrow lead, followed by a bunching of Farkas and Schleifer and Jones, and, behind them, Buchwald. A plurality of 38% are undecided. Analyzing the recent poll, Primaries for Progress finds that while Schleifer’s high ad spending has increased his name recognition, his support share among voters who learn more about the candidates stands on par with Farkas and Jones.

Schleifer’s spending through March was over three times the total outlays by Farkas and Jones, and nearly five times those of Buchwald and Carlucci, according to a Sludge review of FEC data.

A “Punch Back” Against The Pledge

After the pledge to divest from pharma holdings was announced, Barrett Seaman, chair of the Editorial Board of the Hudson Independent, wrote that Adam Schleifer initially refused to join the pledge as a choice to “punch back” when confronted by it on short notice.

The Schleifer campaign then put out a statement and video on June 9 calling the pledge a “coordinated attack” sent to him with only an hour to respond, writing: “if elected to Congress, I would put in place whatever measures necessary and appropriate, including a blind trust for holdings, to further demonstrate the fierce independence I have brought to every job I have ever had.”

Schleifer had floated the idea of a blind trust in the past. On May 3, in a video Q&A on Facebook with the Westchester Young Democrats, Schleifer said, “I would look at something like a blind trust or whatever it would be, and consider that possibility.”

While Schleifer’s endorsement of a blind trust is short of the pledge’s call to liquidate all pharma holdings, it could eventually be judged consistent with the rules of the proposed Ban Conflicted Trading Act that has been introduced by congressional Democrats (H.R. 6401, S.1393) to mitigate conflicts of interest. Current congressional rules do not require members to divest their personal financial investments while in office, even in industries they oversee on their committee assignments. The Ban Conflicted Trading Act would require members of Congress to either liquidate their stock holdings or put them in blind trusts, with cases judged by the Select Committee on Ethics.

The pledge continued to touch off sparks this week, as Allison Fine rescinded her participation in it and told Sludge that Schleifer’s commitment to place assets in a blind trust was “the right move.” Fine blamed the “political ploy” of springing the pledge on Schleifer on Evelyn Farkas and said, “The much more important issues are the lack of campaign finance reform and an unfair tax code that allows so much money to pour into campaigns and politics.”

Castleberry-Hernandez also withdrew from the pharma liquidation pledge and said she would explain her reasons on Facebook. The pledge would also affect Farkas, who when announcing it volunteered to divest pharmaceutical company stocks she owns that are worth between $2,000 and $31,000.

At the same time, Schleifer acknowledged in his video response to the Westchester Young Democrats’ question last month about pharma divestment that voluntary campaign finance pledges can be effective. Schleifer signed the No Fossil Fuel Money pledge, which eschews large campaign contributions from fossil fuel industry executives, lobbyists, and PACs in order to encourage greater independence in elected officials.

The campaign of David Carlucci, a founding member in 2011 of the breakaway Independent Democratic Conference (IDC) that caucused with Republicans in the state Senate, did not respond with his reasons for taking the pharma divestment pledge.

After blocking progressive legislation on a host of fronts including tuition assistance for the children of undocumented immigrants and a state single-payer health care system, the IDC was disbanded in 2018 and six of its eight members were defeated in primaries that year. Carlucci held on to his seat by 1,892 votes, around 8 percent of the 24,240 votes cast in the state Senate District 38 primary.

In Carlucci’s current congressional race, 13% of his contributions have come from donors listing their occupation as “President”—an indication of continued support from business interests. During the years of New York Senate gridlock following Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s 2010 election, the real estate, charter school, and health care industries previously backed IDC members’ campaigns.

Pharma Pledge Fallout

Asked about the divestment pledge, the Schleifer campaign told Sludge that “If his opponents approached the question of how to ensure industry does not have influence over policymaking from a place of integrity, they would have announced their own divestment for financial interests they have in companies that build weapons of war and profit off of bombs; they would have sworn off the thousands of dollars they receive from corporate PACs and from family members representing coal and fracking companies and, ironically, ‘big pharma’; and they would have sworn off funding received from predatory payday lenders.”

Schleifer’s response invokes a recent report by The Intercept on contributions to former defense official Evelyn Farkas from prominent individuals in the defense industry. Wellesley Daniels, campaign manager for Farkas, tells Sludge of last week’s pledge, “Only one candidate in this race was unwilling to divest from the pharmaceutical industry. It’s the same one who is using millions of his drug company inheritance to try to buy this election: Adam Schleifer.”

Nonprofit head and attorney Mondaire Jones has racked up endorsements from progressive leaders such as Rep. Ocasio-Cortez, Senators Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders, the Working Families Party and others. On Jones’ reasons for signing the pledge, campaign manager Charlie Blaettler told Sludge, “Sky-rocketing pharmaceutical prices have deepened the healthcare crisis in this country and prevented so many Americans from receiving the treatment they need. Mondaire signed the pledge because voters should know that their representative is willing to take on the pharmaceutical industry and isn’t personally dependent on their profits.”

We PAID Act

In an April 20 online town hall, the activist group Rockland United tweeted that Schleifer did not respond to their question about a drug pricing bill in Congress—the We PAID Act—and said the candidate disabled the chat function, tagging the Westchester College Democrats and multiple news organizations.

In an email to Sludge, Schleifer’s campaign said for the first time that the candidate “unequivocally supports the We PAID Act.” The bill, introduced in July 2019 by Democrat Chris Van Hollen of Maryland and cosponsored by Republican Rick Scott of Florida, would require drug manufacturers to license drugs developed with federal funding as subject to price restrictions set by an independent Drug Affordability and Access Committee.

Before coming out in favor of the bill, Schleifer’s campaign website put his position in line with that of House Democrats, whose Lower Drug Costs Now Act (H.R. 3), passed by the House in December 2019, would allow Health and Human Services to negotiate lower drug prices. Schleifer’s website also calls for establishing a public option to buy into Medicare, capping out-of-pocket drug costs for Medicare beneficiaries, and requiring rebates if drug prices increase faster than the pace of inflation, among other stances.

But for over a month after the Rockland United question, local activists had been calling on Schleifer to take a position on the We PAID Act. Regeneron has been in the headlines for being at the front of the pack in the development of an antibody cocktail for COVID-19, which has been financed through a $92 million partnership with the federal Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA). Regeneron’s work to research a COVID-19 treatment that uses monoclonal antibodies is under the extension of a 2017 contract, in which public funding accounts for 80 percent of costs and Regeneron puts in 20 percent.

If Regeneron were to announce successful trials of its coronavirus drug, the value of the company’s stock would likely surge—on April 29, for example, Gilead’s shares jumped 7 percent on positive news of the drug remdesivir as a potential COVID-19 treatment. A March op-ed in the New York Times highlighted that despite huge public funding of drug development, the federal government still lacks mechanisms to ensure that treatments from taxpayer support are kept affordable, in part due to the lobbying power of the pharmaceutical industry.

Schleifer has received a total of $42,800 in contributions from multiple Regeneron executives and employees, and he has received nearly $60,000 from employees of two of the company’s law firms.

Through the first quarter of 2020, 34 of Schleifer’s contributions came in small donations categorized as those of $250 or under, totaling $8,468. For comparison, Farkas’ campaign had 427 small donors through March, raising almost $97,000; Jones’ campaign had some 410 small donors as of that same disclosure date, raising nearly $90,000; Buchwald’s campaign had 139 small donors, raising close to $32,000; and Carlucci’s campaign had 48 small donors, raising over $11,000.

“Adam Schleifer has continuously tried to deceive voters by obscuring the source of his campaign’s funding and has only reluctantly supported the We PAID Act, which would prevent companies from charging the American people exorbitant prices for drugs developed using federally-funded research, and only after months of pressure,” Jones campaign manager Blaettler said. “Voters in NY-17 deserve better than an out-of-touch pharmaceutical heir attempting to purchase an election.”

Regeneron and Trump National Golf

In March, Dr. Leonard Schleifer attended a White House event with the coronavirus task force and pharmaceutical company executives, where President Trump referred to him—by some reports, affectionately—as “Lenny.” While Regeneron develops a COVID-19 treatment with federal funding, the company is a member of the largest biotech trade association, BIO, in an industry that spends millions on lobbying and public relations against drug pricing measures. Pharmaceutical industry executives and lobbyists mingle at Trump golf clubs for access to the president and to foster communication channels with administration officials.

Dr. Schleifer, who was awarded the number one spot atop the City & State rankings of the Westchester Power 50, told CNBC in March that Regeneron would keep any COVID-19 treatment “affordable,” saying, “It doesn’t do us any good, if we want to save lives, to make something that’s not affordable.”

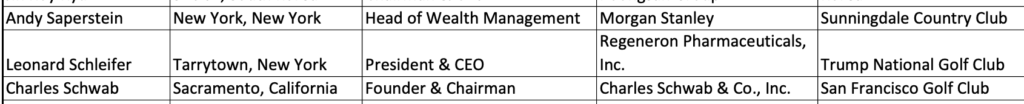

As Regeneron enters human trials for its COVID-19 treatment in partnership with an office under the Department of Health and Human Services, Dr. Schleifer golfs at the Trump National Golf Club Westchester, which he listed this year as his home club with the PGA Tour.

The Trump Westchester Facebook page features a May 2019 photo of Dr. Schleifer golfing there, and displays his name on a Club Championship board in a photo from July 2018. In 2015, the Wall Street Journal reported that Regeneron was cutting back its executive perks, including Leonard Schleifer’s $18,500 golf membership, but did not mention which particular club.

Sludge asked Adam Schleifer’s campaign if Dr. Leonard Schleifer was a member of Trump’s Westchester country club and the campaign referred the question to Regeneron’s media department, which did not respond to multiple requests for comment. The campaign wrote, “Adam is not a member of the Trump National Golf Club and has never been a member of any golf club.” Adam’s current residency in the district is at his parents’ house in Chappaqua, but the campaign would not provide an answer on Dr. Schleifer’s potential membership——full golf, corporate, or other—at the Trump Westchester club, where as of 2015 dues ran $9,200 per year.

Dr. Schleifer has criticized pricing practices of other pharmaceutical companies, telling Forbes in 2018 that a Pfizer executive is “not entitled to a fraction of the GDP.” Regeneron was recently recognized as a civic leader by Points of Light, a volunteering organization that runs programs with companies’ social responsibility efforts. However, Regeneron’s pricing for a cholesterol drug came under criticism in May 2016 by the independent Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER). Dr. Schleifer disputed their calculation that the treatment should cost 67 percent less as “unscientific.” Dr. Schleifer’s 2018 pay package of $26.5 million put him in the top three highest-compensated CEO’s in the pharma industry.

Lobbying on Drug Pricing

Regeneron is a member of Biotechnology Innovation Organization (BIO), a trade group representing over one thousand biotech companies, which has been lobbying on “reasonable pricing provisions” in relation to the coronavirus. Adam Schleifer’s financial disclosure lists stock in pharmaceutical company Gilead, another BIO member, worth between $1 million and $5 million, his second-highest drugmaker asset. Gilead’s high drug prices were called out by Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.) in a congressional hearing last year.

James Love, director of Knowledge Ecology International, an intellectual property NGO, tells Sludge, “When a drug company executive says he will make a product ‘affordable,’ it’s almost meaningless, unless it becomes a legally binding commitment that has some structure. One easy question to ask is if the US public will have to pay higher prices that the company charges in other high income countries like Canada, UK, France, Germany.”

According to figures from the Center for Responsive Politics, BIO spent over $12.2 million on lobbying last year and nearly $3 million so far in 2020. A June 2018 report by the Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington (CREW) found that “In 2017, BIO spent more than $9.3 million lobbying the federal government on issues including drug importation, Medicare Part D, the 340B drug discount program, and orphan drugs which are medications for rare diseases.” BIO also put out public relations campaigns, with videos blaming insurance companies and pharmacy benefit managers for marking up drug prices.

BIO’s lobbying in the first quarter of this year topped well over $3 million, retaining heavy-hitting firms including Akin Gump, Baker & Hostetler, Covington & Burling, Farragut Partners LLP, and Steve Elmendorf’s Subject Matter. As the coronavirus pandemic grew through March, BIO’s own in-house lobbying touched on two dozen drug pricing measures, such as H.R. 3 and the Forcing Limits on Abusive and Tumultuous Prices (FLAT) Prices Act of 2019, which would enable lower-cost generic drugs to come to market earlier. A 2018 corporate responsibility report from Regeneron put its BIO membership dues at $375,461.

For its part, Regeneron spent over $1 million in lobbying last year, retaining two outside firms in addition to its own activity, and is up to $370,000 so far this year, on “Patent issues relating to biopharmaceutical manufacturers; intellectual property rights.”

“On the issue of pharmaceutical drug pricing, we have encouraged the federal government to consider the total revenue from sales, over time, to determine if the prices should be lowered or the exclusivity reduced,” IP expert Love said. “This is a different, and sometimes more efficient way to address the unfair and unreasonable prices of products, since the reasonableness of prices often is dependent upon how many units are sold, and when the government was funding the R&D, how deep was the federal subsidy.”