The figure of $30 trillion has been hovering over the Democratic presidential primary since Joe Biden exclaimed in the Oct. 15 debate that it would be an astronomical amount to pay over 10 years for Medicare for All.

Biden’s campaign doubled down on the $30 trillion gambit on Twitter, adding that “it will be paid for in part by raising taxes on middle class families.” Biden’s Tweet did not bother to correct his erroneous debate claim that a cost of $3 trillion annually would be “twice what the entire federal budget is.” (In fact, President Trump’s 2020 federal budget request was for $4.75 trillion, a 7.7% increase over 2019, which was a 7.25% increase over 2018.)

“How are we going to pay for it?,” Biden asked from the stage, a question also lobbed at Sens. Sanders and Warren by the other single-payer-skeptical candidates and by commentators in the debate follow-up.

With different financing options, confusion abounds on which middle- and upper-class income brackets would possibly see tax increases, and by how much, to pay for Medicare for All. At the same time, there is general agreement among policy analysts that Medicare for All would significantly reduce overall health care costs, when considering insurance expenses, for the 52% of people in the middle class, while virtually eliminating expenses for the 29% of people in the lower class. But it’s also possible to budget for Medicare for All without increasing taxes at all on the top 20% in the upper-class—or even the top 5% or top 1% of earners.

A recent report by the National Priorities Project and the Poor People’s Campaign, called the Moral Budget, proposes a major new source of funds that could be used for Medicare for All: cuts to unproductive military spending and the cost of foreign war operations. With hundreds of billions annually in Pentagon budget reallocations, it becomes possible to budget for Medicare for All without any additional taxes whatsoever on taxpayers, even on the upper-class—the 5% with incomes over $250,000 per year, and the richest 1% with incomes over $1 million—while guaranteeing truly universal coverage. This budgeting path would also not apply any new sales taxes, even on non-essential goods. With its savings, it’s possible to pay for Medicare for All while taking taxes that voters would pay entirely off the table. Its primary new revenue source would be an income-based premium that employers would pay instead of their current health insurance costs, with small businesses saving at greater rates.

A big-picture view of the budget

It’s possible to clear up the budget picture and the various funding options for Medicare for All by viewing them in the context of some federal budget background.

The net annual cost of a single-payer health care system in the U.S., accounting for increased usage and subtracting savings from efficiencies, would be $2.93 trillion per year, according to a 2018 study by the Political Economy Research Institute (PERI) at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst. This nearly $3 trillion figure is what underpins the 10-year gross—not net—price tag of around $30 trillion for Medicare for All (or M4A, for short). Importantly, the cumulative savings of Medicare for All over 10 years would be $5.1 trillion, compared to the current health care system (PERI study, p. 3).

After accounting for the current $1.88 trillion in annual public health care funding, the PERI researchers calculated that the system would need to raise an additional $1.05 trillion from new sources. For context, the $4.75 trillion federal budget for 2020 stands at around 20% of the U.S. Gross Domestic Product of $20.5 trillion, which comprises part of the approximately $98 trillion in total U.S. wealth.

“Regardless of the specific funding framework utilized for Medicare for All, all households and private businesses will be able to pay into the system an average of 9.6 percent less than they are presently contributing to the U.S. health care system,” the PERI study concludes.

The Moral Budget’s proposals of military savings would reduce the M4A target by about one-third, counting for $350 billion per year. Some examples of its potential savings include the following: closing half or more foreign military bases ($90 billion); stopping Iraq, Afghanistan, Yemen, Syria and other war operations ($66 billion); ending foreign military financing ($14 billion); and canceling the dysfunctional F-35 program ($15 billion).

U.S. military spending is larger than 144 other countries combined, but even that scale doesn’t communicate its immensity and dominance over yearly budgets set by Congress. Nearly half ($623 billion in FY2018) of the federal discretionary budget goes to the military, defense contractors, and weapons makers, who spread their manufacturing out through all 435 congressional districts in order to make reallocation politically difficult. Counting all 10 major sources of defense spending, according to a May report by the Center for International Policy, 2019’s actual spending on military and war will total $1.254 trillion—virtually the same amount as the entire FY2018 federal discretionary budget of $1.262 trillion, which includes all federal agencies, Cabinet departments, and scientific research.

M4A’s annual funding target of $1.05 trillion minus the Moral Budget’s $350 billion in savings leaves the new goal of $700 billion per year to budget towards single-payer, in order to realize its overall savings (through systematic efficiencies) of an average of $510 billion per year, when implemented.

An April 2018 proposal from the office of Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) details several revenue packages to get there.

The first is a 7.5% income-based premium paid by employers instead of their current employer health insurance costs, which would raise $390 billion per year. Another would be eliminating some current tax subsidies, mainly the preference that excludes employer-paid premiums from payroll and income taxes, which would raise $420 billion per year. Taken together, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) can recognize the resulting $810 billion in revenue far surpassing the $700 billion target, with the surplus able to be applied back to small employers.

Another option in the Sanders plan would be a 4% income-based premium paid by households, instead of current basic insurance costs, raising $350 billion per year. According to the plan, a typical family of four making $50,000 would save $4,400 and pay just $844 per year for free-at-point-of-care health care; families under the poverty level of $29,000 in income would not pay this premium. Economics professors Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman of the University of California, Berkeley, calculate that an individual with $50,000 in income would receive a net gain of $11,000 under Medicare for All.

Another possible revenue source in Sanders’ financing package is to start income-based premiums at the higher level of $250,000 in taxable income (applying to the top 5% of U.S. households). At the highest end, this option would move income above $10 million from a marginal tax rate of 37% up to 52%.

The PERI study, for its part, proposes raising $458 billion as follows: a sales tax of 3.75% on non-essential items such as consumer electronics, furniture, home appliances, and miscellaneous goods like tropical wood and unwrought silver ($196 billion); a recurring tax of 0.36% on all wealth over $1 million ($193 billion); and taxing long-term capital gains as regular income, like short-term capital gains are ($69 billion). Economist Dr. Robert Pollin, of PERI, summarizes the savings under this plan: “Net health-care spending for middle-income families that now purchase insurance for themselves would fall by fully 14 percent of their income.”

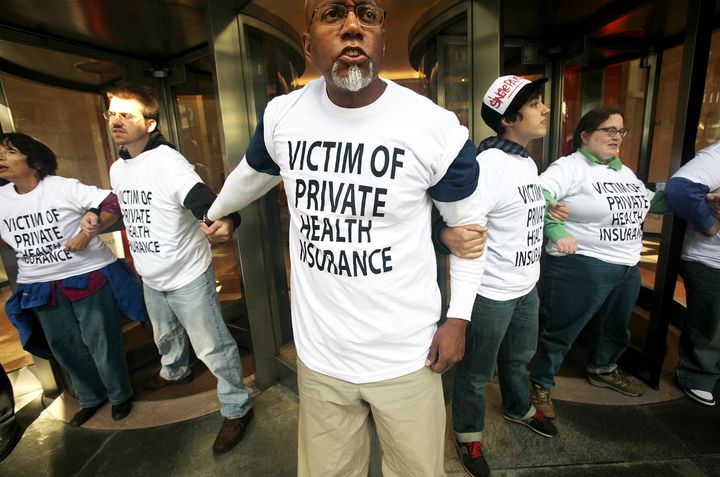

Medicare for All yields net savings for 90-95% of taxpayers

The U.S. system is already privately spending well over a trillion dollars annually on health care costs. “Private health insurance spending grew 4.2% to $1,183.9 billion in 2017… while Out of pocket spending grew 2.6% to $365.5 billion in 2017,” according to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). The current patchwork system of private insurance results in vastly unequal outcomes— 530,000 families file for bankruptcy every year from medical bills. A study last year by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) at the University of Washington found that despite its highest spending, the United States ranks 27th in the world for its levels of health care.

The PERI study’s lead author wrote in a March Wall Street Journal op-ed, totaling public and private layouts, “As of 2017, the U.S. spent $3.3 trillion on health care—17% of gross domestic product. Germany, France, Japan, Canada, the U.K., Australia, Spain and Italy spent between 9% and 11% of GDP on health care.” In 2018, the total rose to $3.65 trillion.

In July 2018, the CBO said that 2016 private spending on health care, counting payments by private insurers and consumers’ out-of-pocket expenses, totaled $1.7 trillion. Clearly, with an aging population, the “2030 Problem” of senior care for Baby Boomers will lead to continuing increased costs under the status quo: the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, a federal agency, estimated that U.S. health care spending would reach about $5.7 trillion by 2026, over 1.56 times its current levels.

Overall, if the purpose of Medicare for All is greater human health through delivering universal health care, and the primary goal is to budget an additional $1.05 trillion per year to pay for it, then the proximate goal for a possible next Democratic administration is to enable the CBO to meet its statutory requirement in scoring out the economic costs and benefits of a single-payer system.

There’s lots more work to do to document the projected savings by taxable income bracket (e.g. by quintile or decile) under Medicare For All, since voters care about how much they’re paying in taxes (if, that is, personal-income-based premiums end up being part of the funding mix). But as longtime single-payer advocates Physicians For a National Health Program have been noting on Twitter in the Democratic primary debates, if truly universal health care is a priority of the U.S. federal government, it can be budgeted for—even without any new taxes.

The history of proposals of Medicare for All in the U.S. goes back at least to 1944’s “Economic Bill of Rights.” More recently, Sen. Sanders’ bill proposes a system like Canada’s, where private health care providers deliver services with public financing. This is different from, for example, England’s National Health System—in Canada, privately-provided care is still the norm, but there are no more private insurers for basic coverage. Single-payer would cover the following under Bernie Sanders’ Medicare for All Act: hospital visits, primary care, medical devices, lab services, maternity care, and prescription drugs as well as vision and dental benefits. Sanders’ bill would not nationalize health care providers and related industries, like pharmaceuticals.

Health insurance companies would not be permitted to offer competing coverage in these areas, as PNHP explains, but speciality treatment and supplemental coverage could still be purchased as currently. The transition to Medicare for All would happen over four years, with a program to assist current health insurance industry employees in transitioning to new careers. The Veterans Affairs health system and the Indian Health Services would continue to operate as they do now. The House version of the bill is sponsored by Rep. Pramila Jayapal (D.-Was.); previous versions were introduced by Rep. John Conyers (D-Mich.), in 2017 and in prior Congresses.

The potential benefits of Medicare for All extend far past savings from efficiencies in the health care system and negotiations of prescription drug prices. In September, policy analyst Matt Bruenig calculated from U.S. Census data that single-payer would reduce poverty by about 22%. “8 million of the nation’s 42.5 million poor people would not be poor if they did not have to pay medical out-of-pocket expenses like deductibles, copays, coinsurance, and self-payments,” Bruenig writes.

Mayor Pete Buttigieg put himself at the forefont of Democratic presidential candidates advocating—in recent months, at least—for a “public option” instead of Medicare for All. From studying other countries’ implementations, PNHP estimates that keeping a role for for-profit private insurance companies foregoes approximately four-fifths of the efficiencies of a single-payer system. Mayor Buttigieg’s shift to attacking Medicare for All came, Sludge’s Alex Kotch reported, as over 100 donors with upper-level positions in the health care industry made large donations to his campaign between July and September.

The pharmaceutical industry, to take one entrenched interest as an example, devotes a war chest to battling Medicare for All and defending its profit margins: by 2023, global pharmaceutical revenue will hit $1.5 trillion, according to IQVIA, a health info company. At an average 17.1% profit margin, that’s $256.5 billion in annual profits available for drug makers to reinvest in efforts to keep prescription prices at high levels. Earlier this month, Kotch reported on Big Pharma contributions to an industry front group, The Coalition Against Socialized Medicine, which is spending seven figures on a campaign against Medicare for All. Also this month, investigative journalist Andrew Perez reported on how investor-owned hospitals are chief backers of the Partnership for America’s Health Care Future, a dark-money organization created last year to erode public support for Medicare for All.

To be sure, it’s possible to allocate the Moral Budget’s $350 billion in annual military savings towards other ends, such as the Green New Deal’s renewable energy infrastructure, and instead rely more centrally on progressive taxes to fund Medicare for All. But with health care continuing to be a top issue for voters, presenting a clear financing path for health care plans is likely to remain a top issue in the Democratic primary, and the path above requires no additional taxes on any income brackets (even the super-rich).

A May poll by Data For Progress found that a majority of Democratic primary voters in 12 congressional districts would disapprove of their representative opposing Medicare for All. With a clearer picture of the savings from the Moral Budget’s reallocation of Pentagon spending, voters can debate the merits of a single-payer system in the U.S. ahead of the 2020 elections without needing to consider any new personal income taxes in order for every American to be covered with comprehensive health care.