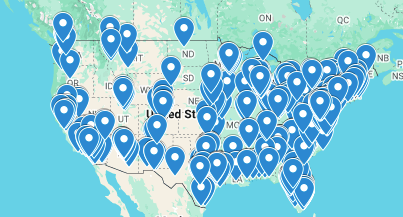

More than a dozen city and state governments have active contracts with U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement—even though many of the jurisdictions have adopted, or are advancing, policies that limit coordination with ICE.

The contracts range from vehicle parking to firing range rentals and data system access, according to a Sludge review of data from USASpending.gov. Recipients include Cottage Grove, Minnesota, a suburb near the Twin Cities; the planning organization for San Diego County, California, where city lawmakers are passing new laws to counter ICE raids; a pair of towns in New York, where state leaders are proposing to block local law enforcement agreements with ICE; and a state agency in the certified “welcoming city” of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Sludge first reported on ICE contracts with what were called "sanctuary cities” in 2018, and several of those same contracts remain in place, renewed in the years since. Recently in New York, the Hudson River Park Trust said it would not be renewing its decades-long parking contract with ICE when it is scheduled to end on June 30, following attention from Sludge’s reporting. Over a dozen New York State and City elected officials, as well as activists and community groups, are calling on the Trust to immediately end the parking arrangement at its Pier 40 garage.

The City of Hartford, Connecticut is also moving to end an ICE contract with the Hartford Parking Authority (HPA) that has been in place for a decade, according to Cristian Corza-Godinez, deputy chief of staff of Hartford, who spoke with Sludge. In a Jan. 27 letter reviewed by Sludge, Hartford Mayor Arunan Arulampalam requested that the agency's CEO terminate its contract with ICE “immediately.”

Since February 2015, the HPA has held a contract for secure parking of ICE vehicles for the Enforcement and Removal Operations (ERO) division of the Boston Field Office, according to federal contract data.

“The contract was brought to our attention about two weeks ago through a constituent submission on our city website,” Corza-Godinez told Sludge. “Once we learned of the contract, we immediately moved to cancel it.”

Altogether, ICE parking contracts worth $188,000 have been awarded to the Hartford municipal agency, though reported outlays have been lower. The current contract, started in July 2021, has paid the HPA nearly $65,000 and is set to end on July 31, 2026. “The HPA is actively moving to cancel the contract as soon as administratively possible,” Corza-Godinez said. The HPA is governed by a six-person board, with five commissioners appointed by the mayor and approved by the city Council.

In March 2016, Hartford enacted a resolution deeming itself “officially a Sanctuary City,” with provisions in its code that “Hartford police officers shall not make arrests or detain individuals based on administrative warrants for removal entered by ICE,” among other things.

Connecticut’s immigration rules have been targeted by the Trump administration, which named it a “sanctuary state” in a Department of Homeland Security (DHS) list last year, along with Hartford and several more of its cities. Connecticut enacted the Trust Act in 2013, a measure restricting the types of information that local law enforcement are allowed to share with federal immigration authorities, strengthening the law with updates in 2019 and further amending it in 2025.

In Cottage Grove, Minnesota, located southeast of the Twin Cities, ICE has awarded contracts worth $750,000 since 2020 for rental of a firing range training facility named the HERO Center. Of that ceiling, the ICE agency has paid about $290,000 to the city. Its larger active contract for the firing range rental has an end date of Aug. 31, 2026, subject to a two-year potential extension, while a smaller one is slated to end on July 31. Minneapolis and St. Paul have “separation ordinances” that prohibit police and other city employees from asking about immigration status, with the former referring to itself as a “welcoming city.” The Twin Cities region has been thrown into crisis by the Trump administration operations.

Cottage Grove’s ICE contract met opposition last year from an immigrant advocacy group at a Lutheran church in the city. Peggy Nelson, a resident, proposed a resolution to the Cottage Grove City Council in August that would bar ICE agents from the HERO Center and the city, among other steps, and said at a public meeting that the proposal had not been placed on the agenda. Asked about Cottage Grove’s revenue from ICE, Phil Jents, communications manager, referred Sludge to a Jan. 25 Facebook post by Mayor Myron Bailey. The mayor states that the HERO Center is governed by a Facility Operations Committee (FOC), which renewed the facility’s agreement in summer 2025, and that it requires access for all federal agencies. Bailey’s post added that Cottage Grove police “will not participate in federal immigration enforcement activity in our community.”

In California, the regional planning association San Diego Association of Governments (SANDAG) has been awarded $263,000 by ICE’s Operations and Support federal account since July 2021. The contracts provide access to the ARJIS criminal justice network containing cross-jurisdictional data on crime cases, arrests, suspects, and property files. The current contract’s end date is June 30, 2026, with the option to extend for three years, and could be worth up to $401,000. In a comment to Sludge, ARJIS Director Anthony Ray said that the contract was with the DHS Homeland Security Investigations (HSI) division. “ICE ERO has not had access to the ARJIS system since 2019 because the agency has not signed a California Law Enforcement Telecommunications System subscriber agreement with the state of California,” he said. “ARJIS does not assist with issuing or obtaining warrants of any kind, for any agency,” Ray added.

However, it’s not clear that data from ARJIS would remain siloed—the DHS maintains a joint information-sharing program with HSI and ERO, and a recent ICE memo says that HSI prepares “target packets” for ERO.

The SANDAG regional association includes the City of San Diego, where last year the City Council unanimously gave introductory passage to the Due Process and Safety Ordinance that limits local law enforcement coordination with ICE in response to an increase in raids. In addition to requiring that ICE agents have a judicial warrant to enter “non-public City facilities,” the measure, Item S400, “aligns City practices with state law on federal enforcement cooperation and data privacy.” The ordinance will go through a “meet-and-confer” phase with local labor organizations before returning for a final vote. Earlier this month, the City Council unanimously passed a resolution showing opposition to ICE’s tactics and authorizing San Diego's city attorney to initiate or join lawsuits supporting Minnesota and Illinois in legal challenges to DHS.

Also in San Diego County, the City of Escondido has a purchase order from DHS, awarded again in January, worth up to $67,500 for firing range rental; the contract was approved administratively by the Escondido Police Department, the mayor told the local news outlet L.A. TACO. The arrangement has been in place for over a decade and last month met renewed local protests.

The Philadelphia Parking Authority (PPA) is an agency of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, overseen by a six-person board appointed by the governor. The PPA entered into a one-year contract with ICE on Sept. 30 worth $54,000 for parking spaces for “vehicles for ICE Homeland Security Investigations Philadelphia.” No outlays have been reported yet from the deal. The agency previously held an ICE parking contract from September 2015 to March 2017, from which no payments were reported.

PPA spokesperson Martin O’Rourke told Sludge, "The contract you reference refers to a garage owned by the federal government that the PPA is under lease to manage. The PPA does not own that garage facility.” O’Rourke did not respond to follow-up questions about whether the PPA might consider the contract at the garage it manages, such as at a forthcoming public meeting, the next of which is scheduled for Feb. 17.

Last year, Mayor Cherelle L. Parker’s top attorney described Philadelphia as adhering to the “welcoming city” framework that ensures equal treatment for immigrants, a designation awarded in 2023, as opposed to the term “sanctuary city.” The city said that a 2016 executive order remains in place on ICE cooperation, directing city officials not to detain people from ICE orders without a signed judicial warrant. The Philadelphia mayor’s office did not respond to a request for comment on its views on the PPA’s ICE parking contract.

The Pennsylvania governor’s office did not respond to a request for comment on ICE’s agreement to park vehicles in a PPA-managed garage. In Pennsylvania, more than 50 law enforcement agencies have 287(g) agreements under which they perform immigration-related activities under ICE supervision. Under these partnerships, local police are involved in identifying, arresting, and processing individuals who are targeted for deportation.

Philadelphia City Council lawmakers are moving to strengthen limits on local ICE coordination through an “ICE OUT” legislative package introduced last month, including barring city agencies from collaborating with ICE. “We are taking action to ensure that local resources are not used to support ICE activity,” said Councilmember Quetcy Lozada in a statement. The package, which was cheered by a rally outside City Hall, would codify the city’s non-participation in the 287(g) program. Philadelphia District Attorney Larry Krasner recently joined prosecutors from around the country in a coalition pledging to charge federal officers, like ICE and CBP agents, who break the law.

In New York State, Gov. Kathy Hochul recently announced a legislative package that would restrict ICE cooperation, including by prohibiting the use of taxpayer-funded resources or personnel for federal civil immigration enforcement. In the state’s Erie County, the town of Lancaster holds two active ICE contracts worth a combined $213,000, one set to end in September 2026 and the other in April 2027. The former is for “secure storage for ICE/ERO/Buffalo Field Office special response team (SRT) assets” and has paid the town $80,000 so far, while the latter is for rental of an indoor firing range and has paid nearly $83,000.

Since 2021, the town of Islip, located in Suffolk County on Long Island, has held a contract for gun range rental “for DHS/ICE/ERO New York” that is worth up to $46,000 and is scheduled to end on June 30. New York immigrant advocates and Democratic lawmakers are encouraging Hochul to support the New York for All Act, which would go further than ending 287(g) agreements by barring local governments from sharing information with ICE and from government facilities.

Other jurisdictions also hold contracts with ICE, as state and local officials consider varying approaches to ICE cooperation.

In Michigan, the County of Oakland holds a contract awarded in January 2024 worth up to $113,000 for access to CLEMIS, a law enforcement management system. The database is used by ICE officers “assigned to the ICE/ERO/DETROIT area of responsibility.” The deal is slated to end Mar. 31, 2026, with a potential three-year extension. Michigan Attorney General Dana Nessel, a Democrat, is encouraging residents to report “concerning behavior” by federal officials in their neighborhoods. Nearby Detroit was designated as a welcoming city in 2022 and residents, as well as some city lawmakers, are calling on the City Council to strengthen rules on ICE’s presence.

Kansas City, Missouri holds a contract with ICE worth up to $97,000 for access to a wireless communications system used by law enforcement, a deal scheduled to end on May 31, with a three-year continuation option. Last month, the city passed a five-year ban on the construction of non-municipal detention centers, soon after ICE toured the area to evaluate a warehouse site for the purpose.

The Ohio Department of Administrative Services also holds a contract for radio access for ICE that is worth $75,000 and scheduled to end on May 30. Ohio Democrats, in the minority in the state legislature, have introduced bills to increase transparency of ICE’s operations and limit data-sharing, while Republicans in the majority are proposing measures that would mandate local law enforcement’s cooperation with ICE detainment notices.

ICE also holds contracts with the Utah Communications Authority for radio network services and Pennsylvania's Montgomery County Fire & Rescue Training Academy for firing range rentals. A years-long ICE contract with the Denver Health and Hospital Authority, one that paid $12,000 for “unarmed guard services” at a correctional care medical facility, was noted as closed out last month.

The National Immigrant Justice Center (NIJC), one of several nonprofits calling on Congress to rein in ICE and CBP’s patrols assaulting communities, argues for disentangling federal immigration enforcement efforts from local governments. In Minneapolis and other cities, dozens of deaths and injuries are being caused by ICE and CBP agents, from practices torched by civil liberties groups as unconstitutional.

This accountability reporting is only possible thanks to subscribers—readers like you who appreciate our focus on money in politics. If you value this coverage of current ICE contracts, support our independent journalism at $100 for a year and get full access to Sludge stories.