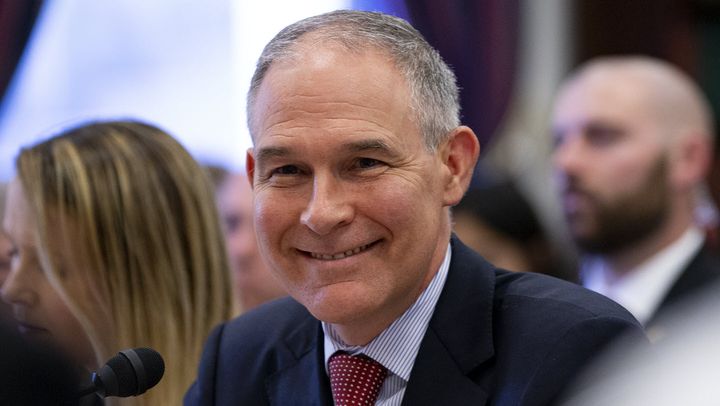

Former Environmental Protection Agency administrator Scott Pruitt resigned in June 2018 amid a cloud of ethics scandals, seemingly too corrupt even for the Trump administration. Now he is attempting to regain a position in the government — despite the fact that he has continued to make questionable moves on behalf of the oil and gas industry since leaving his post.

In late April, Pruitt filed paperwork to run for the open U.S. Senate seat in Oklahoma to replace retiring Republican Sen. Jim Inhofe. Pruitt is now running in the June 28 Oklahoma Senate Republican primary election against multiple candidates, including Rep. Markwayne Mullin and the Inhofe-endorsed Luke Holland, a former staffer for the senator.

The seat is considered solidly Republican, so whichever candidate emerges from the primary will very likely end up with a six-year term in the Senate.

During his two and a half years in the Trump administration, Pruitt was accused of paying below-market rent on an apartment owned by a health care lobbyist who also happened to be married to an oil lobbyist, spending public funds lavishly on items like a soundproof phone booth and customized fountain pens, and more. Last month, the New York Times reported on a 2018 report by an Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) special agent that concluded that Pruitt had routinely pressured his security detail to drive fast with sirens and lights on because he was often running late for appointments.

Pruitt first made a name for himself as Oklahoma’s attorney general, where he worked hand-in-hand with the fossil fuel industry to try to block Obama-era environmental regulations. According to Follow the Money, in total the oil and gas industry donated $274,000 to Pruitt’s various state office campaigns over the years, making it his second-highest donor industry, behind lawyers and lobbyists.

Since resigning from Trump’s EPA four years ago, Pruitt has continued to do oil and gas companies’ bidding as a strategic consultant. He may have even helped one of his client’s companies skirt environmental standards through a process he brought about as EPA administrator.

In his first campaign ad, “I’m Back,” Pruitt claimed that news outlets that repeatedly reported on his ethical lapses, such as the Washington Post and the New York Times, were his “enemies.”

“They think they canceled me, but guess what? I’m back,” Pruitt says in the ad while tossing copies of the papers in a trash can.

A Spin Through The Revolving Door

According to Pruitt’s recently filed financial disclosure statement, after he resigned from the EPA, he began working as a manager at two Tulsa, Oklahoma-based consulting firms: ESP Consulting, starting in October 2018, and Clear Worldwide, from May 2020. For his work, ESP paid Pruitt $533,000 in 2021.

According to the disclosure, one of Pruitt’s consulting clients was Red Apple Group, a New York-based real estate and oil and gas conglomerate owned by billionaire John Catsimatidis, CEO of Manhattan grocery store chain Gristedes.

In the 2020 election cycle, Catsimatidis and his wife Margo donated more than $800,000 to Trump Victory, a joint fundraising committee affiliated with the Republican National Committee and Trump’s Make America Great Again PAC. Catsimatidis’ daughter Andrea, a Red Apple executive and chair of the Manhattan Republican Party since 2017, chipped in another $200,000 to Trump Victory, according to FEC records.

Red Apple Group also owns United Refining Company, an oil refining and marketing company based in Warren, Pennsylvania, that has sought to dodge environmental standards using a process Pruitt championed while working in the Trump administration.

While head of the EPA, Pruitt undermined the Renewable Fuel Standard, a program passed by Congress in 2005 that aims to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and U.S. dependence on foreign oil by requiring transportation fuels to include at least 10 percent renewable fuels made from plant-based sources like ethanol and biodiesel.

Pruitt initially sought to roll back the standard through the regulatory process, proposing a reduction in the blending requirement for 2018 — but he faced resistance from a bipartisan group of ethanol-industry backed lawmakers. Instead, he acted unilaterally, dramatically increasing the number of waivers the EPA granted through the Small Refinery Exemption (SRE), a provision of the 2005 law that allowed small refiners to argue that compliance with the standard would cause them disproportionate economic hardship.

While the provision had only been used sparingly prior to his tenure, under Pruitt, the EPA approved nearly all SRE waiver applications it received. The process saved the oil industry hundreds of millions of dollars.

In expanding the use of the SRE waivers, Pruitt went against the advice of EPA staff who warned that doing so would look bad because of Pruitt’s long-standing support from the oil industry, according to documents obtained through the Freedom of Information Act by the Renewable Fuels Association.

“To grant the exemptions would be a clear violation of Mr. Pruitt’s oath of office,” former EPA adviser David Schnare wrote in an email to staff in July 2017. “Second, granting improper exemptions would look like a quid pro quo to the refinery industry — something that could only harm the reputation of both the agency and Mr. Pruitt.”

In December 2019, the Red Apple subsidiary United Refining applied to the EPA for an SRE waiver so it could be exempt from the blending requirements that year. In July 2020, the company sued the EPA after not receiving a response on its application within 90 days, as required by law. In November 2021, the EPA formally denied United Refining’s application, concluding that refiners of all sizes should be able to comply with the requirement, since they could offset the cost of compliance by charging higher fuel prices.

The law firm that represented United Refining in the matter was Cleveland, Ohio-based Baker & Hostetler LLP, which Pruitt listed as another one of his three clients on his recent financial disclosure statement. Baker & Hostetler also works in government lobbying and has represented several clients with business before the EPA, according to Senate lobbying records.

In 2017, during Pruitt’s tenure, the firm lobbied the EPA on behalf of the American Chemistry Council on “policy issues relating to the chemistry industry, including the deployment of plastic piping in infrastructure projects.” Baker & Hostetler has also lobbied the EPA on behalf of oil companies including Denbury Resources and Southern Company.

In 2015, Baker & Hostetler assisted Pruitt when he, as Oklahoma attorney general, attempted to sue the federal government to stop it from enforcing the Clean Power Plan on states, which would have required them to develop and implement plans to achieve carbon dioxide emissions standards. According to a report by the Southwest Times Record, Baker & Hostetler provided its expertise to Pruitt free of charge.

Pruitt’s campaign has raised about $140,000 so far for his campaign, according to FEC filings. Members of the Catsimatidis family gave him four donations of $2,900, and other donors include the executives of oil and gas companies including Alliance Resource Partners, Lucas Oil Products, and Rhoades Oil Company.

Early polling of likely Republican primary voters conducted between April 25 and May 11, shortly after Pruitt officially declared his candidacy, found that his opponent Mullin had a commanding lead, with 38 percent of respondents saying they would vote for him if the election were held that day.