In the competitive Democratic primary in New Mexico’s Third Congressional District held last June, supporters of candidate Teresa Leger Fernandez tried to paint her opponent, former spy Valerie Plame, as an outsider compared with Leger Fernandez, who had been involved in local politics for years. In the weeks leading up to the election, they got a signal boost for their talking point from a pair of mysterious groups who had produced ads using the campaign’s imagery and were putting thousands of dollars behind targeting them to voters on Facebook.

“Born and raised in Las Vegas, New Mexico, Teresa Leger Fernandez has spent more than 20 years fighting for water rights, health clinics, affordable housing, and voting rights,” reads one of the spots that was sponsored on Facebook by a page with fewer than 20 likes calling itself Perise Practical.

Shortly after the Perise ad began appearing in feeds, another unknown group called Avacy Initiatives, which appears to be closely affiliated to Perise, spent $250,000 on TV ads that highlight Leger Fernandez’s local roots.

The ads were part of a winning strategy. Leger Fernandez defeated Plame in the primary—a win that New York Times’ Jennifer Medina chalked up to ”Leger Fernandez’s emphasis on her deep roots in the district”—and she went on to prevail in the general and now serves in the U.S. House of Representatives.

But to this day, next to nothing is known about the groups behind the pro-Leger Fernandez ads, including from where they get their funding.

The groups’ Federal Election Commission (FEC) filings are signed by David Krone, a former chief of staff to former Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid, and Practical’s website says, “we believe in and are fighting for affordable healthcare, equality, voting rights, and a better future for everyone.” The groups were incorporated in Delaware as tax-exempt entities in December 2018, and are likely in the process of applying to be considered “social welfare” nonprofits with the Internal Revenue Service (IRS).

While nonprofits are required to report their spending on politics to the FEC, they do not have to report information about their donors, like political action committees and super PACs do. Nonprofits are also not required to report information about their donors to the IRS following a rule change enacted by the Trump administration. Before the change, nonprofits had to report their donors to the government, though all personal donor details were redacted by the IRS before the documents were made public.

The Rise of Dark Money

Tax-exempt groups have been players in politics for decades, including trade associations like the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, issue groups like the National Rifle Association, and 527 organizations like the Democratic Governors Association. But it wasn’t until the Supreme Court’s ruling in Citizens United v. FEC, decided exactly 11 years prior to the date of the article’s publication, that pop-up nonprofits like Perise Practical and Avacy Initiatives began spending big on elections.

Citizens United allowed corporations, including nonprofits, to spend money from their general treasuries on politics and to donate to super PACs, which are political committees that can raise and spend unlimited amounts on independent expenditures. The Court deemed restrictions on corporate political spending as violations of the First Amendment, building upon the Court’s 1976 decision in Buckley v. Valeo that determined campaign spending limits restrict the quantity of protected speech. The only restriction on political nonprofits is that they can not coordinate with candidates or their campaign committees, though the FEC’s rules against coordination are weak. Operatives for campaigns and outside groups like nonprofits are allowed to talk to each other and confer on “issue ads” that don’t explicitly support candidates. Campaigns can provide materials to nonprofits and can signal their needs to groups through tweets and other public communications.

In the election cycles following the Citizens United ruling, nonprofits played an increasing role in elections, peaking in the 2012 cycle with $312 million in independent expenditures, according to the Center for Responsive Politics. While direct nonprofit spending has tapered since 2012, the groups have increased their giving to super PACs, mixing their dark money with funds from the PACs’ disclosed donors, a situation that has been labeled “gray money.” In the 2020 elections, $95.6 million in direct nonprofit spending was reported to the FEC, but a tally by the Center for Responsive Politics of super PAC filings and ad spending estimates the total amount of dark money in the 2020 cycle to have topped $750 million.

“Voters and viewers don’t know who is paying to influence them, but the candidates receiving this support almost certainly do,” said Jennifer Ahearn of Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington. “That is an environment rife for corruption: funders can spend vast sums on public influence campaigns without voters understanding that the ad may also have the effect of indebting the candidate to the special interests of the corporation, wealthy individual, or union who actually funded it.”

Sludge reviewed FEC data and found that gray money spending impacted congressional elections in nearly every state in the 2020 elections. Scroll over the map below to see the gray money groups that spent money in your state.

The largest outside sending group in the 2019-20 cycle was Senate Leadership Fund, a gray money super PAC affiliated with Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.). The group spent $293 million in support of Republican Senate candidates and against Democratic candidates, such as boosting the successful re-election of Sen. Susan Collins (R-Me.) and attacking Sen. Gary Peters (D-Mich.). Its largest donor was the nonprofit One Nation, which functions as a dark money affiliate. Democratic congressional leaders also have affiliated super PACs that raised millions from dark money sources.

Another Shot at Transparency

Democrats in Congress have tried before to force transparency upon political nonprofits. In 2010, House Democrats passed a bill called the DISCLOSE Act that would have required groups including nonprofits to report to the FEC their political donors who have given them more than $10,000 within 24 hours of making a political expenditure. The bill was defeated in the Senate twice that year, falling just one vote shy of the 60 votes needed to invoke cloture and bypass Republican procedural barriers the second time around. The bill was rejected in the Senate again in 2012 and has not been taken up since, though it was introduced again in 2017.

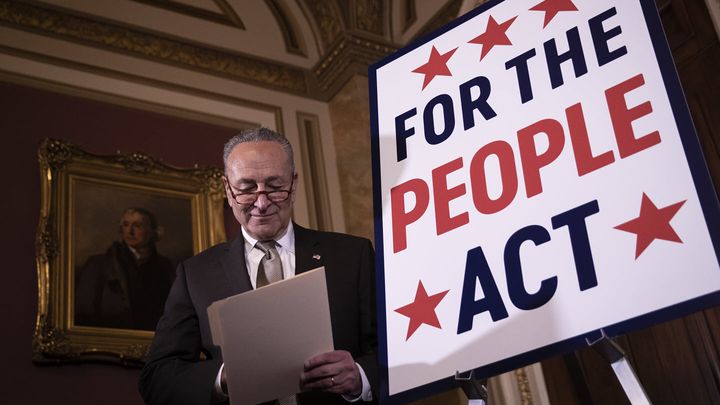

Now, House Democrats have put the DISCLOSE Act in a larger package of campaign finance, government ethics, and voting rights reforms called the For the People Act (H.R. 1) that they are planning to vote on next week. A companion measure is expected to be introduced soon in the Senate and will be given the bill number S. 1, an indicator that the Democrats want to be seen as prioritizing the measure.

In H.R. 1, the DISCLOSE Act would prohibit political nonprofits and other groups from taking contributions from foreign nationals and require them to report to the FEC the names of donors who give more than $10,000 in a reporting period, the date and amount of donations, and the aggregate amount donated by donors. Nonprofits would not have to disclose amounts received in the ordinary course of business, among other exceptions, and the bill says this includes union membership dues. The disclosure provisions would also apply to expenditures related to federal judicial nomination communications, besides those appearing in publications that are not controlled by political parties.

Ahearn said that groups will likely find loopholes in these provisions, but that the overall bill should provide additional protections.

“There’s no such thing as an airtight system, and so there isn’t any doubt in my mind that some dark money will continue to make its way in,” said Ahearn. “For example, one of the major new disclosure requirements has exceptions for amounts received in the ordinary course of business, funds that were subject to a donor restriction, and situations where there are threats of harassment or reprisal. Any of these could be abused to improperly avoid disclosure. That’s why it’s important to view the bill as a whole—making FEC enforcement actually functional, for example, is a way to ensure abuses don’t overwhelm the effectiveness of the rules overall.”

Another disclosure measure in H.R. 1 would force all ads to list their top 5 donors, either as text in videos and graphics, or as a voiceover in audio ads. If the ads are too short or too small to include the information, the advertisers must include a link to a website where that information can be found.

H.R. 1 is expected to pass in the House, but its future in the Senate is less certain. The Senate is evenly split between the parties and the Democrats control it because the vice president, who makes tie-breaking votes, is a Democrat. It has become routine over the past 15 years or so for the minority party to threaten a filibuster of just about all substantial bills, requiring 60 votes in favor of overcoming that procedural hurdle and proceeding with debate.

It’s unlikely that nine Republicans will join Democrats to break a Republican filibuster threat, and it’s unclear how many Senate Democrats want to change the rules to eliminate the 60-vote procedural hurdle so they can pass bills like the For the People Act and other measures opposed by Republicans. But some groups that have been working on this issue are not giving up.

“We’re activating our 4 million grassroots members to apply pressure on members of Congress,” said Bawadden Sayed, a spokesperson for a nonprofit called End Citizens United. “The integrity of our Democracy is at stake, so we’ll leave no stone unturned in our efforts to pass this historic bill.

“Since the assault on the Capitol Building on January 6, there is a new focus on restoring our democracy. It’s too early to rule out a surge of support that includes members of Congress from both parties or procedural measures to ensure it is passed,” said Sayed.

End Citizens United has conducted polling that shows broad public support for the provisions of the For the People Act. In August, 84% of voters said they support making all political contributions, including anonymous dark money spending, fully transparent, with 67% saying they would strongly support such a measure.

Read more Democracy news from Sludge: