This is a bonus edition of the members-only SLUDGE REPORT, for the launch week of The Brick House Coooperative.

In the build-up to Election Day, interest spiked again in how the country could rid itself of a founding flaw and finally abolish the Electoral College. The undemocratic anachronism responsible for the outcomes of the 2000 and 2016 presidential elections again threatened to overturn the popular vote.

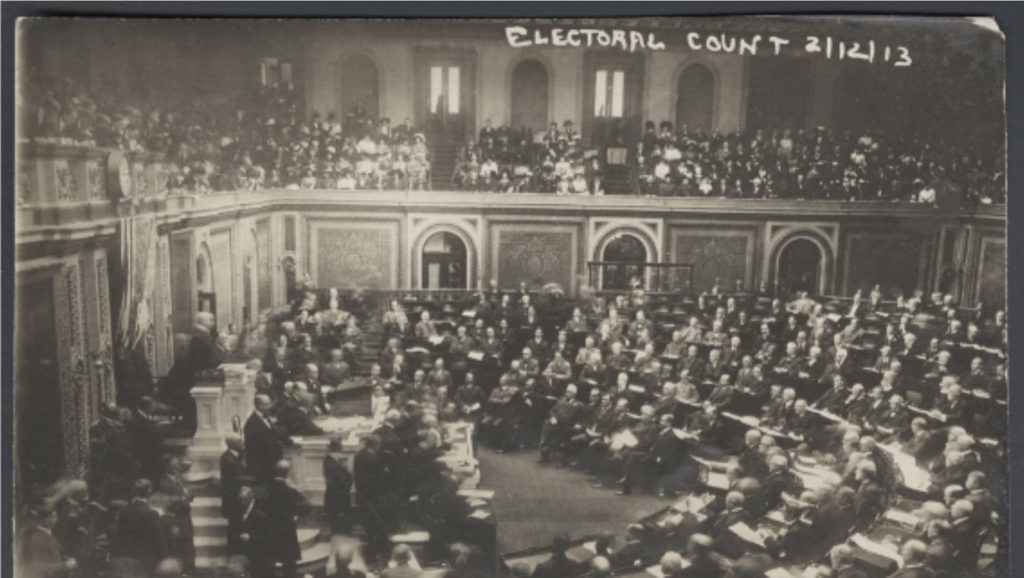

Cries rose up on social media for Congress to take up a Constitutional amendment and bury the abomination once and for all. “Abolish the Electoral College” op-eds were dusted-off: on its 19th Century scandals, on the many 20th Century attempts at repeal, and on how it is really time for a more democratic election process in America.

The Electoral College thoroughly distorts our politics, but politicians in many battleground states evidently prefer it to a national principle of one person, one vote. That’s a problem because the likeliest path to passing a Constitutional amendment for a new process requires a two-thirds majority in both the U.S. House and Senate, and approval by at least 38 of 50 state governments—a high bar.

Since the election, there’s been sustained attention on the urgency of transitioning away from the Electoral College before it exacerbates an even greater Constitutional crisis than the one playing out now, in the lawsuit filed by Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton seeking to overturn states’ certified election results. On Nov. 30, political writer Ryan Cooper calculated that a flip of just 0.02% of the total vote, or 33,139 flipped votes across three key states, could have let Trump win the Electoral College again despite losing the popular vote. Cooper found that the margins are, incredibly, tightening: switching just 58,706 votes could have meant a President-elect John Kerry; only 38,868 votes going the other way could have given Hillary Clinton the Electoral College.

Reporter Jon Walker highlighted a path forward for the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact (NPVIC), a non-profit project founded in 2006 that’s recruiting states—towards the critical mass of 270 Electoral College votes—to commit to allocate their lot to the presidential candidate who receives the most popular votes, rendering the Electoral College moot. “So far, states with 196 electoral votes have joined, so only 74 more electoral votes are needed,” Walker wrote.

To date, the NPVIC has been enacted into law in 15 states and the District of Columbia, and it has passed a total of 41 state legislative chambers. But crucially, Walker points out, there’s a way to largely bypass recalcitrant state legislators and governors: “There are 17 states not currently part of the compact that allow citizen ballot initiatives—together, they control a total of 114 electoral votes.”

By my review, states with ballot initiatives that haven’t yet thrown in are as follows, with their Electoral College votes in parentheses—some of which, marked with an asterix, have a chamber that has passed NPVIC before, just as additional info: Alaska (3), Arizona* (11), Arkansas* (6), Florida (29), Idaho (4), Maine* (4), Michigan* (16), Mississippi (6), Montana (3), Nebraska (5), Nevada** (6), North Dakota (3), Ohio (18), Oklahoma* (7), South Dakota (3), Utah (6), and Wyoming (3).

Via another path, there are five large state governments that haven’t yet adopted the NPVIC that would be just enough to reach the threshold: Pennsylvania (20), Ohio (18), Michigan (16), Virginia (13), and Minnesota (10). With no state legislative chambers flipping from red to blue in 2020, it will still be a very large lift to convince these state governments: in Pennsylvania and Michigan, Republicans control the House and Senate. Ohio remains a Republican triumvirate. Minnesota has a Republican-controlled Senate.

But the states needed can be counted on one hand: the national popular vote compact can be adopted by passing ballot initiatives in, for example, Arizona, Florida, Michigan, and Ohio, or by enacting a law in Michigan, Minnesota, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Virginia.

If a Democratic Congress Had Led The Way

There have been past windows of time when more of these five states might have come closer to passing the NPVIC. In 2009 and 2010, Democrats controlled the governorships and state Houses (but not Senates) of Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Michigan. In 2009, Democrats held the governorship and Senate of the Commonwealth of Virginia, and they currently have a trifecta there. In 2009 and 2010, Democrats had the Senate and House of Minnesota, and in 2013 and 2014 they had a Democratic trifecta.

At the congressional level in 2009, Democrats had a strong majority of 59% in the House—after retaking the White House as well in 2008—and could have held hearings then on legislation that was introduced to end the Electoral College. Early on in the 111th Congress of 2009-2010, now-retired Rep. Gene Green, from a Texas district encompassing parts of Houston, re-introduced his H.J.Res. 9, the Every Vote Counts Amendment, which would have dissolved the Electoral College and instituted a plurality vote. But the amendment was promptly referred to a subcommittee of the House Judiciary, where it was left to die with no further actions taken and no cosponsors that Congress.

Shortly after, former Rep. Jesse Jackson, Jr. introduced his H.J.Res. 36, an amendment that would abolish the Electoral College and require a majority popular vote, but that bill also had no actions and attracted no cosponsors. A Senate amendment introduced by former Sen. Bill Nelson to have Congress determine how the presidential election winner was declared also went nowhere in the 111h Congress. A stronger push by congressional Democrats, including public hearings on equal representation for all citizens, could have raised the issue to prominence in more state legislative chambers, perhaps bringing aboard Virginia or Minnesota over the past decade.

Biden Barely Squeaks Through

John Koza, the founder of the organization behind the NPVIC and a computer scientist, told me that while most congressional Democratic leaders support both ending the Electoral College and the NPVIC, there was no real interest among the Democratic-controlled House in 2009 in holding a vote on an amendment.

“If there had been a hint of a hearing, we would have gotten involved,” Koza said. “It would have been a major step forward. But the threshold for a Constitutional amendment is so high, and lots of members of Congress have a position to not support any Constitutional amendment.”

Koza also recalled that Democratic Party leaders in 2009 believed they had built a “Blue wall” that was supposed to give their party a virtual lock on the White House, which he said made it difficult to get the NPVIC passed in Democratic-controlled legislatures. New York, for example, didn’t enact the NPVIC until April 2014, the 11th state to do so—generally with New York Senate Republican support, and with a history of debate in the Democratic-controlled Assembly.

In the newest presidential battleground states of Arizona and Georgia, voter turnout surged this year, which Koza points to as further evidence that voters will cast ballots at higher rates in competitive contests. Individual votes counting equally has been missing in the “Red” and “Blue” state system under the Electoral College, part of the reasons why American voter turnout in recent national elections has lagged back at 30 of 35 comparable countries. But 2020’s turnout was 65.9% in Arizona and 67.7% in Georgia, according to the latest data from the United States Election Project, up from 56.1% and 59.8% in the 2016 general election.

Koza still sees the path to ending the Electoral College as running through states, as opposed to starting in a future Congress. “When Trump won, Democrats got real interested, Republicans less interested,” Koza said. Even with a significant popular vote win, “Biden just barely squeaked through,” he said, suggesting that states that are trending Democratic in national elections might be inclined to join the compact’s ranks. Minnesota and the Democratic-trifectas of Maine and Nevada tend to fit that description, with Michigan and Wisconsin in the running.

The recent pickups of the NPVIC in state legislatures after the blue wave of the 2018 midterms is a story of political progress that is not well known. Four states, comprising one-quarter of the total jurisdictions behind the NPVIC, adopted it in 2019, as did another handful of state chambers. In a time when Mitch McConnell takes pride in his nickname of the “Grim Reaper” of legislation in Congress, Colorado, Delaware, New Mexico, and Oregon took steps to rehabilitate public trust in democracy.

This week on his nightly news show, MSNBC host Chris Hayes kept the focus on the dangerous absurdity of the Electoral College with a few segments on the movement to dustbin it, following up on his June podcast interview with Jesse Wegman, author of a book on the history of the institution.

“The thing itself is a slapdash compromise thrown together at the end of the Constitutional Convention as they were on their way out the door,” Hayes said. “Scrapping the Electoral College in favor of a simple popular vote would be an enormous change, requiring either a Constitutional amendment or a coordinated interstate compact, and both would be hard, they would represent huge structural shifts in how the country is governed.

“But that’s the history of this country,” Hayes said. “we used to not have equal protection and due processes enshrined in the 14th Amendment. Before the 17th Amendment, we didn’t even directly elect our senators, women couldn’t vote until 100 years ago. We need large-scale democratic reform, like we’ve done before, if we are going to save American democracy.”

Hopefully small-d democrats will make it clear to the incoming Biden administration that guaranteeing equal democracy is a first principle. As a presidential candidate, Joe Biden was one of just a few hopefuls (with Senator-elect John Hickenlooper and John Delaney) to tell the Washington Post he did not support eliminating the Electoral College.

Read more from Sludge: