This free edition of the SLUDGE REPORT was made possible by subscribers, who directly support our independent newsroom and enable us to continue our investigative reporting.

The 2020 elections revealed how the machinery of U.S. democracy is creaking and corroded.

Creaking, because of chronic underfunding of the U.S. election system by Congress and state governments; corroded, because of many politicians’ hostility to making voting accessible.

This year, voters kept running up against suppression measures. Why were there pitched battles over providing the option to safely vote by mail during a pandemic? Why were early voting locations so limited in many states? How could it be that a restrictive state law signed by Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis disenfranchised nearly 900,000 voters?

These problems are nowhere near new. Democracy experts, state advocacy organizations, and community groups had long identified these structural problems with election administration and voting access, and raised ways to address them. In 2020, the U.S. is projected to reach 66.8% voter turnout, but over recent national elections it has placed distantly back at 30 of 35 comparable countries in voting-age population casting ballots.

National Democrats have been critical of restrictive voting policies and they have called out Republicans for voter suppression efforts. But Democratic leadership has not not made ballot access a legislative priority, and when they had a chance to address these issues without Republican obstruction they did not take it.

For a period in 2009, Democrats had full control of the federal government: a strong House majority and a 60 vote majority in the U.S. Senate, enough to bring bills to a vote and send to the new Democratic president to sign.

Rank-and-file Democrats had filed bills that session that would have introduced a vote-by-mail option in every state, set up early voting locations and secure election infrastructure, established same-day voter registration, and restored voting rights to people who completed felony sentences. But Democratic leadership did not support bills as cosponsors and let them die in committee.

The 111th Congress certainly had enough on its plate. The new Obama administration and the Democratic-controlled Congress were immediately confronted with responding to the global financial crisis, and its first year was taken up by the all-consuming process of negotiating the Affordable Care Act. Major changes to election processes would have been hotly opposed by Republicans, and only a tiny percentage of bills become laws. Even in Democratic-controlled Congresses, political capital is not abundant. Some bills in Congress are primarily messaging bills, rather than laws meant to be passed here and now.

But if Democratic leaders had done more to get behind these reforms over the years they could have passed them when they had a chance, the results would have significantly defended voting rights during the past decade’s tilt towards disenfranchisement. Even if House bills came up short of a floor vote in the Senate, their example might have inspired state governments to move strongly to adopt vote-by-mail programs or same-day voter registration. Clear commitments from congressional Democrats to defend the fundamental right to vote might have increased trust among skeptical voters who stayed home in 2016 after turning out for change in 2008.

Congressional Democrats have not had a similar window of opportunity for reforms since, and depending on the outcome of the two Senate runoff elections in Georgia in January, they might not see it for many more years. From 2008 through the end of the Obama administration, Democrats suffered a net loss of 64 House seats and 12 Senate seats, plunging them into the minority in each chamber. After a historic 2018 midterms wave, Democrats lost a net of at least 10 seats in the 2020 election and currently hold a tiny majority of 222 House seats to the GOP’s 210 seats, with three contests outstanding.

Remarkably, the top three House Democratic leaders then are the same as now: Speaker Pelosi, Majority Leader Hoyer, and Majority Whip Clyburn, who were just last week reelected to lead again in the next 117th Congress. Despite this year’s election losses, Speaker Pelosi and her team were elected by voice vote without intra-party challenge from the progressive wing or another caucus. Speaker Pelosi had previously pledged this Congress would be her last as Speaker, but hasn’t mentioned the vow since. Over in the Senate, Chuck Schumer and Dick Durbin were reelected by acclimation to their leadership posts, having worked together under Harry Reid’s leadership in the 111th Congress.

Here is a look at how congressional Democrats squandered an opportunity to secure voting rights for all Americans over the past decade, which could have countered the rise of the Tea Party and the Trump administration.

A Democratic Senate Slips Away

After the 2008 election, Democrats rung in the 111th U.S. Congress on Jan. 3, 2009 with 256 of 435 seats in the House. What started as 57 Democratic-aligned senators grew to 59 with the appointment of Ted Kaufman to then-Vice President Biden’s former seat, then the appointment of Kirsten Gillibrand to Hillary Clinton’s former seat. In a dramatic April 2009 move, Pennsylvania Sen. Arlen Specter switched parties to give Democrats a pending total of 60 votes, which was sealed with the swearing-in of Al Franken in July 2009, after eight months of lawsuits over his election’s recount.

But when Ted Kennedy died on August 25, 2009, Senate Democrats were pushed back one under the 60-vote threshold vote that since a Senate rules change in 1975 has been needed to overcome a filibuster. Among the results of this gridlock: public faith in government declined since 2010, while frustration with elites’ unresponsiveness resulted in the Tea Party making an appeal for economic austerity while passing tax cuts for the wealthiest and the largest corporations. In late 2011, the Occupy movement sprung up in New York City partly in response to an inadequate government response to the Great Recession, skyrocketing economic inequality, and towards the cause of a more responsive, participatory form of democracy.

Good government groups and election experts, for their part, had been advocating for a number of measures to expand voting access and upgrade archaic election management. Many of these election reforms were in-hand from previous Congresses, and were introduced or re-introduced in a variety of legislation in the 111th Congress:

H.R.1604 – Universal Right to Vote by Mail Act of 2009

Sponsored by California Rep. Susan Davis, who represents a district that encompasses parts of San Diego, the bill, introduced March 2009, would have introduced “no excuse required” vote by mail in every state. The ACLU wrote in support in a June 9, 2009 letter, “H.R. 1604 would ensure that all Americans have an equal opportunity to vote by mail in federal elections for any reason. This bill would give all voters the choice of voting by mail by eliminating the unnecessary, burdensome, and often intrusive requirements that some states impose on voters requesting absentee ballots.” The Brennan Center for Justice was also tracking the bill in its list of federal election reform legislation in the 111th Congress.

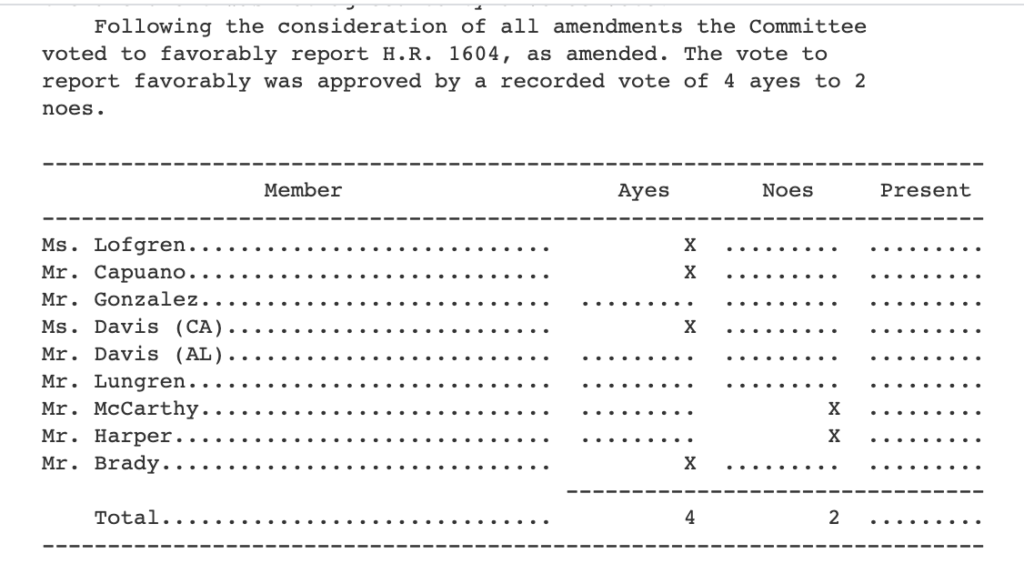

While the amended bill was approved by the Committee on House Administration on June 16, 2009, along with two companion measures that would have helped voters track absentee ballots and prevented a state’s chief elections official from serving on federal campaign committees, the package never received a floor vote. The bill’s 50 cosponsors were mostly made up of progressives; none of the top dozen House Democratic leaders signed-on as cosponsors, except for one of eight chief deputy majority whips at the time, Rep. Jan Schakowsky of Illinois.

The nonpartisan election reform group FairVote noted at the time that committee members opposed the bill, without evidence, on the grounds that it would open up the system to voter fraud. In fact, cases of fraud in vote by mail are vanishingly rare, and vote by mail is associated with higher voter turnout in states that have developed mail voting programs. This resulted in the compromise amendment that election officials maintain on record a voter’s signature before they mail an absentee ballot and verify the signature before the returned ballot is accepted. The committee’s report recorded the 4-2 aye vote, but no floor vote was ever scheduled and it died:

If the bill had been passed by the House and its companion bill in the Senate had been passed, and if President Obama had signed the resulting agreement, the battles over vote by mail ballots—especially feverish during this 2020 election—might have played out very differently. One can imagine that more than the five states that currently have mail voting would have adopted mostly-by-mail elections, where ballots are proactively mailed to every registered voter.

Rep. Davis, who just retired from her seat, continued to reintroduce her package guaranteeing access to vote-by-mail, saying last year, “With many states curtailing voting rights, it’s time for the federal government to exercise its constitutional responsibility and ensure Americans’ access to the ballot box.” Increased vote-by-mail access was included as part of the sweeping H.R. 1 reform package passed by Democrats, by a roll call vote of 234 to 193 in the House, which did not stand a chance of being picked up by the Republican-controlled Senate.

H.R.253 – Critical Election Infrastructure Act of 2009

Sponsored by Florida Rep. Alcee Hastings, who represents a district encompassing parts of Fort Lauderdale and West Palm Beach, the bill would have made grants available to states for equipment and training in election sites, including early voting locations. Before the 2008 election, Rep. Hastings and other Democratic members of Congress had written a letter to Florida Gov. Charlie Crist and Florida Secretary of State Kurt Browning to request expansion of early voting.

Upon its introduction in January 2009, the bill was referred to the Committee on House Administration, with no actions taken. The only leading Democrat it acquired that month among its six cosponsors was again Rep. Schakowsky. At the time, the committee’s chair was Rep. Robert A. Brady of Pennsylvania with Vice Chair Zoe Lofgren of California, who was also chair of the Subcommittee on Elections. There were nine committee members, six Democrats and three Republicans, none of whom cosponsored Hastings’ bill.

If the Democratic members of the committee had favorably reported the bill to the House for a vote, and if it had been passed and was eventually signed into law, many of the scrambles for election preparation during the pandemic election might have gone better. The HEROES Act contained $3.6 billion for election infrastructure that would have been distributed to states; with a decade of planning, elections might have been more resilient.

Also noteworthy: H.R.5229, the Vote Tabulation Audit Act of 2010, sponsored by progressive Rep. Rush Holt of New Jersey, sought to set standards for transparent vote counting, including early vote locations. The bill was introduced in May 2010 and did not receive any further actions in the Committee on House Administration.

H.R.3957 – Same Day Registration Act

Sponsored by Minnesota Rep. Keith Ellison, whose district encompasses Minneapolis, the bill would amend the Help America Vote Act of 2002 to require states to allow same-day voter registration, including during early voting periods. Introduced in Oct. 2009, it was referred to the same Committee on House Administration, where it died with no further actions. Its 18 cosponsors were mostly progressives, without any members of Democratic leadership or any members of the committee where it was assigned.

Multiple studies have found that same-day registration increases voter participation by an average of 5% in the 21 states and the District of Columbia where it is in place. In the 2012 election, four of the top five states in voter turnout offered same-day registration, and the think tank Demos found that it assists geographically-mobile, lower-income citizens, young voters, and voters of color. This past July, Barack Obama pushed his public positions further in a eulogy for civil rights leader Rep. John Lewis by calling for automatic voter registration and expanded ballot access, countering Republican efforts to restrict the franchise. But if Ellison’s bill had been supported, same-day registration could have been in place nationwide by the 2012 elections.

H.R.105 – Voting Opportunity and Technology Enhancement Rights Act of 2009

Sponsored by long-serving Michigan Rep. John Conyers, who before his resignation represented districts encompassing the west side of Detroit, this package of election reforms would have permitted absentee vote-by-mail, at least 15 days of early voting, made Election Day a federal holiday, and set more voting standards. This VOTER Act from Rep. Conyers—who voted on the 1965 Voting Rights Act—also ensured that no citizens’ vote could be “denied or abridged because that individual has been convicted of a criminal offense,” restoring the right to vote in federal elections to people convicted of felonies upon completion of their term of imprisonment.

Introduced in early January 2009, the bill was referred to several committees, including the Judiciary Committee which Rep. Conyers chaired, and received introductory remarks from its sponsor.

Its final action came in June 2009 when the Judiciary Committee referred it to the Subcommittee on the Constitution, Civil Rights, and Civil Liberties. Five House Democrats joined as co-sponsors, including three members of the subcommittee to which it was referred: chair Rep. Jarrod Nadler of New York, Rep. Sheila Jackson-Lee of Texas, and Rep. Steve Cohen of Tennessee. But the Act died there, and the bill did not have a companion version in the Senate.

H.R.3335 – Democracy Restoration Act of 2009

This bill, sponsored by Rep. Conyers, was introduced in July 2009 and the next month was referred to the Subcommittee on the Constitution, Civil Rights, and Civil Liberties. It “states that the right of an individual citizen of the United States to vote in any election for federal office shall not be denied or abridged because that individual has been convicted of a criminal offense, unless such individual is serving a felony sentence in a correctional institution or facility at the time of the election.” The measure would prevent disenfranchisement of citizens with criminal convictions and allow people with felony convictions to vote upon completion of their sentences, also informing them of these rights after they have ended their imprisonment.

In March 2010, the Committee on the Judiciary held hearings on the bill, but there were no further actions. Among those testifying were Burt Neuborne, Founding Legal Director of the Brennan Center, Hilary O. Shelton, Director of the NAACP Washington Bureau, and Ion Sancho, Supervisor for Elections in Leon County, Florida. In the 111th Congress, the bill attracted 32 co-sponsors, including Senior Chief Deputy Majority Whip Rep. John Lewis of Georgia, as well as two of the eight chief deputy majority whips, Rep. Maxine Waters of California and Rep. Schakowsky.

In cases like the restrictive Florida laws that prevent timely payment of court fees and fines, the bill would “provide for enforcement and remedies for violations of this Act.” An August 2009 blog post from an ACLU legislative analyst praised the bill’s proposal to restore voting rights to nearly 4 million Americans who had been released from prison, building on support at the time by Democratic and Republican governors alike for felony enfranchisement reforms. This month, Trump beat Biden for Florida’s 29 Electoral College votes by over 371,000 votes, a margin of over 3%; the hundreds of thousands of voters disenfranchised by the Republican state legislature might have been the difference. The bill was included in the omnibus H.R. 1.

Rep. John Larson of Connecticut, who was Democratic caucus chair in the 111th Congress, told me in an interview for our previous Sludge Report that when it came to major campaign finance reform legislation, progressives in House Democratic leadership supported a public financing option, but it ran up against the “usual constraints that prevent critical legislation from making it to the floor.” His comments focused on how Democrats who opted-in to a voluntary public financing program could compete with deep-pocketed Republicans across the aisle who might have opted to privately finance bids. But there is also the intra-party dynamic, that public financing grants could support primary challengers to incumbents.

To be sure, the battles over Obamacare and the recovery stimulus were taking up most of the oxygen on the Hill in 2009. But in looking at what held back House votes on Conyers’ package of reforms and others, it’s worth pressing members of Congress on whether they might have been reluctant to pass vote-by-mail, early voting, same day registration, and voter re-enfranchisement because they were worried it might boost election turnout so well that it endangered their position.

After all, nearly two-thirds of the people holding those positions who left the previous Congress landed lucrative jobs lobbying their former colleagues. American democracy might stand a better chance of being rehabilitated in Congress if members can be compelled to finally close the revolving door to industry and instead be incentivized to get long-needed election reforms into laws.

June 25, 2022: This post was updated to convey that the 111th Congress had an increased window of time with 60 votes of Democratic-aligned senators. Originally it referred to the six-week period in the summer after Franken was sworn in and before Kennedy’s death, but the Democratic leadership also had the period starting Sept. 24, 2009, when Kennedy’s successor Paul Kirk was appointed, which lasted into the next year.

Previously in the SLUDGE REPORT: A Decade Later, Dems Again Say They’re Ready to Do Campaign Finance Reform