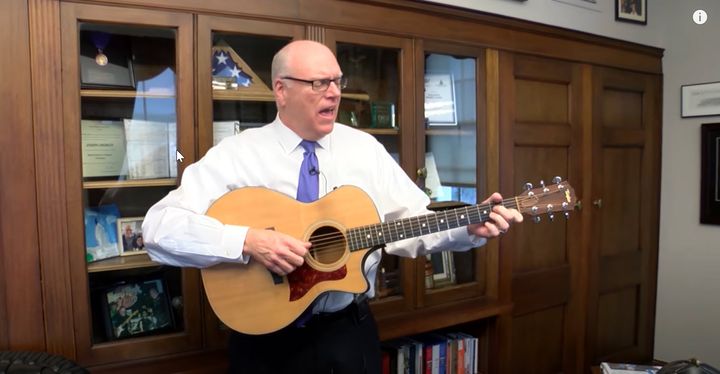

Even the most unabashedly corporate politicians tend to obscure their proximity to special interests, which is why one of the most reliable indicators of lawmakers’ true allegiances is their employment trajectory after leaving office. So what have we learned about former New York Congressman Joseph Crowley, who spent a year inching to the political left in an effort to fend off a rare primary challenger in Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and to position himself for the speakership?

Crowley is taking his talents to K Street to shill for the special interests that once made up his fundraising base.

Approximately one-in-four former lawmakers go on to lobby after leaving office, so many may have been desensitized to the damaging effects of the revolving door. For those who have not yet internalized D.C. cynicism, however, Crowley’s abandonment of principle in favor of a lucrative position working against the public interest is rightly perceived as deeply wrong.

And what one-percenter cause will Joseph Crowley be pushing? As an honorary co-chairman of the Pass USMCA coalition, Crowley will be working to get Trump’s revised North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) through Congress alongside a group of businesses, trade associations, and a former Trump advisor. Among that group are countless corporations whose PAC donated generously to his 2018 re-election campaign, so this latest move may well be best understood as a formalization of his fealty to moneyed interests.

[Related: Shadow Lobbyist Joe Crowley is Poised to Advance Shell Oil’s Tax Interests]

But, you might ask, is this really so bad? Isn’t free trade supposed to be universally beneficial? Putting stylized economic models aside, there are many reasons to be skeptical of how actual free trade agreements unfold in real life. That there are warranted grievances that stem from American trade policy represents one of the few areas where President Trump and progressives might agree. On how to address these grievances, however, they differ drastically, as the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) makes clear.

Although Trump shocked the establishment with his anti-trade rhetoric and fondness for tariffs, his approach to trade agreements has been nothing more than a continuation of past approaches that prioritized corporate interests and marginalized democratic participation. Consider the fact that two-thirds of the language in the USMCA mirrors that in the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) text, a deal against which progressives mounted major resistance and ultimately helped to defeat. Trump called that deal a “disaster” and exited it only three days after taking office.

His new deal, however, includes many of the measures that progressive groups had vehemently opposed in the TPP, like broad protections for pharmaceutical patents, which will keep drug prices high. These and other provisions in the agreement strengthen corporate power and hurt consumers. Meanwhile, although Trump has joined progressives in criticizing NAFTA’s effects on the domestic labor force, labor advocacy groups agree that the new deal’s worker protections are far from sufficient.

While many lawmakers, especially progressives, have long wanted to revise NAFTA, many do not want to replace it with this deal, which fails to meaningfully address many of the critiques of that agreement. Their options for changing the substance of the deal, however, are limited. President Trump negotiated the USMCA under fast-track authority obtained from Congress by President Obama, a set of rules that delegates the legislative branch’s negotiating authority to the President. This guarantees an up-or-down vote within 60 days of when the President submits the text to Congress, limiting congressional debate and prohibiting amendments to the deal.

With Congress having surrendered its constitutional powers, the meat of the negotiations occurs behind closed doors, hidden away from public scrutiny. While the general public is closed out, however, industry insiders are given a key. As a result, modern trade agreements are increasingly vehicles for outrageous corporate giveaways that undermine the public good and often have little, or nothing, to do with trade. Unfortunately, the fast-track process falsely distills all of these complexities into a question of deal or no deal. Pressure to liberalize trade and maintain support from corporate donors has often pushed lawmakers to approve deals, even when they are filled with unjustifiable, pro-corporate measures (that, ironically, are also often protectionist).

In short, the trade negotiation process as currently designed gives corporate America the upper hand. This advantage, however, is not decisive. Sustained public opposition to the TPP eventually killed that deal. Public interest groups are attempting to drum up such pressure again, this time encouraging the administration to renegotiate USMCA, since fast-track authority stops lawmakers from changing the text of the agreement. These entities have largely agreed that the USMCA’s costs outweigh its benefits and do not support passing the agreement as is.

As a leader in Pass USMCA, Crowley is actively working against efforts to subject this trade agreement to some manner of democratic scrutiny. This is hardly surprising; if negotiations are reopened many of the coalition’s members, like pharmaceutical industry giants, could lose some of the ludicrous protections that they secured the first time around.

Crowley will be a formidable ally in this effort to subvert public scrutiny and entrench corporate power. Having spent twenty years in office, he has undoubtedly built solid relationships with countless members who remain in the chamber. As a former member of Democratic leadership, Crowley’s connections and institutional knowledge go beyond those of the average member.

The cryptic nature of trade negotiations further increases the value of this expertise because Crowley is one of a rarefied group who understands precisely how the process unfolds. Who better than Crowley to advise corporate stakeholders on how to manipulate the levers of power to achieve their desired outcome? That this advantage typically goes to the highest bidder means that those working in the public interest face a stacked deck.

Although current law bans Crowley from formally lobbying Congress for one year after leaving office, he can play no less important a role behind the scenes. He can, for example, advise others on who to lobby and how to win their support. Or he can develop and circulate policy proposals in the right D.C. venues so that they enter the policymaking conversation, as he appears to be doing on behalf of the fossil fuel industry at the Bipartisan Policy Center.

In so doing, Crowley joins countless other lawmakers who skirt mandatory “cooling off” periods to access a big K Street paycheck without delay, casting doubt on our government’s resilience to corruption.

Luckily, many lawmakers recognize this threat and are working to close off the avenues by which special interests capture our institutions of governance. H.R.1 (the For the People Act), a landmark set of pro-democracy reforms that tackles issues from campaign finance to voter registration, also includes new restrictions on lobbying. Specifically, it expands the definition of lobbying to include those who counsel “in support of lobbying contacts.” This would subject such behavior to lobbying registration requirements, forcing former lawmakers to actually observe the one- to two-year (for senators) cooling off period.

While H.R. 1 is an encouraging step forward, it does not go far enough. The average representative spends ten years in office, meaning that former lawmakers’ contacts are slow to lose their value. The institution of Congress itself is also slow to change, meaning that a former lawmaker’s institutional knowledge likely retains special value for at least several years. Even a real one-year cooling off period leaves many years in which their knowledge will be sought after by corporate lobbying shops.

Now that they have overwhelmingly passed H.R. 1, lawmakers in the House should consider how to build on this anti-corruption momentum. Representatives can look to the Warren-Jayapal Anti-Corruption and Public Integrity Act for worthy next steps. That proposal recognizes the longevity of former members’ institutional knowledge and responds by banning them from lobbying for life. They should also consider what that piece of legislation might miss; perhaps, for example, former regulators should also face a lifetime ban for everything a normal person would deem to be “lobbying.”

What would the real world impact of such reforms be? Consider a world in which corporate lobbyists were unable to add a ringer like Joe Crowley to their team in a last ditch effort to overcome considerable skepticism of the USMCA among Democrats. H.R. 1’s anti-shadow lobbying provisions might well help the many who oppose corporate trade deals overcome the money of the corporations advocating for them.