In January 2017, President Donald Trump acted on one of his “drain the swamp” campaign pledges by signing Executive Order No. 13770, banning administration officials from leaving government and immediately lobbying their former colleagues and preventing former lobbyists who join his administration from working on issues related to their former clients. But the order is not being enforced, and just last week Trump nominated an administration official who appears to have violated at least two sections of the order to lead the Department of the Interior.

On Feb. 12, Trump selected acting Interior Department head David Bernhardt to lead the agency. Bernhardt is a former natural resources lobbyist who was employed by Brownstein Hyatt Farber Schreck until the moment he joined the Trump administration in 2017. His former clients, including Haliburton, Statoil (now Equinor), Cadiz, and many others in the agriculture, oil and gas, and mining sectors, present significant potential conflicts for his work at Interior.

According to an ethics complaint from government watchdog Public Citizen, filed recently with the Interior Department’s ethics official and inspector general, Bernhardt appears to have violated the executive order by working in the Interior Department to weaken the Endangered Species Act. Paragraph 7 of the order bars administration officials from working on any issues they had lobbied on in the two years prior to joining the administration, and paragraph 6 bars them from working on matters involving specific parties related to their former lobbying employers or lobbying clients. Unlike some other administration officials, Bernhardt did not receive a waiver from these restrictions.

In a recent interview with the New York Times, Bernhardt acknowledge that in late 2017, shortly after joining the administration, he directed David Murillo, the Acting Commissioner for the Bureau of Reclamation, to begin rolling back Endangered Species Act protections for delta smelt and Chinook salmon in order to free up more water for agricultural use. That process is currently underway.

Bernhardt lobbied extensively on the Endangered Species Act, most recently on behalf of the Westlands Water District in Q4 of 2016 when he reported lobbying on “potential legislation regarding the Bureau of Reclamation and the Endangered Species Act.”

The Times article explains that the Westlands Water District would likely be the primary beneficiary of the initiative:

If the protections on the fish were lifted, Westlands would not be the only beneficiary—water would also flow to surrounding water districts. But because of a quirk in California law, Westlands would likely be the main beneficiary, according to Jeffrey Mount, a water management expert with the Public Policy Institute of California. That’s because river water in California is distributed according to a longstanding first-come-first-served system, and Westlands is low on the list.

“Westlands is the most penalized under the current system,” Mr. Mount said. “But if the protections on the fish are relaxed, they will be one of the biggest winners.”

According to the Washington Post, Benrhardt was supposed to recuse himself from work that impacted Westland Water District until August 2018 because of Trump’s ethics order.

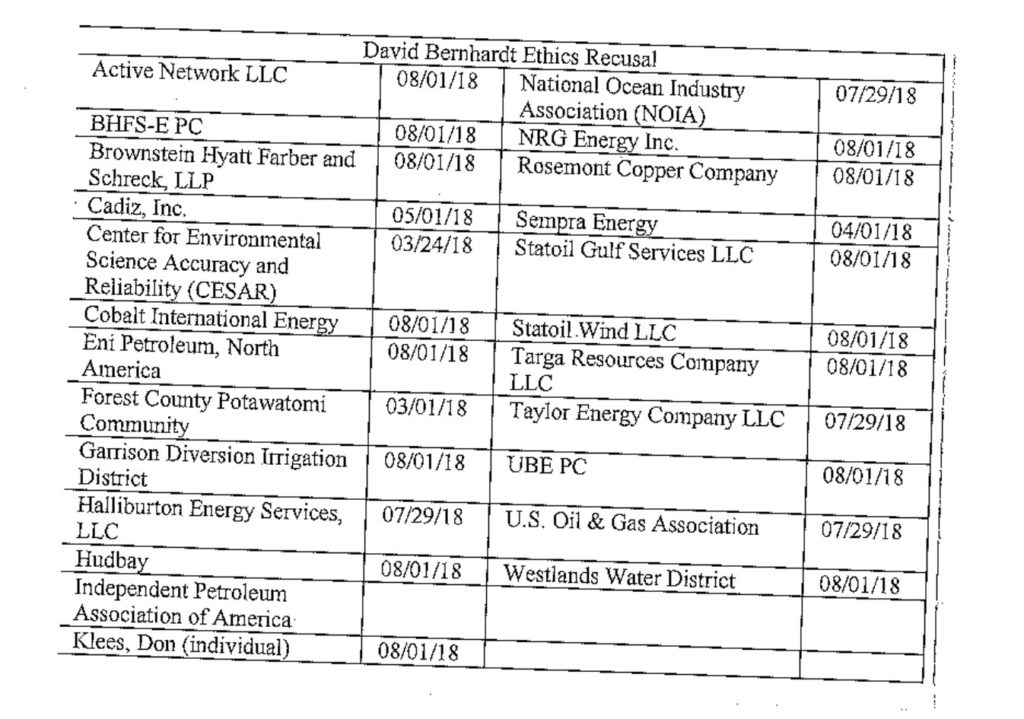

Bernhardt has worked as a lobbyist for so many entities that present potential conflicts of interest with his work at the Interior Department that he carries around a pocket card listing companies and individuals that he is supposed to avoid impacting as he goes about his job.

Public Citizen government affairs lobbyist Craig Holman has filed 30 prior complaints against administration officials for violating paragraph 7 of Trump’s executive order, including a previous complaint against Bernhardt, but all were either dismissed or ignored by the oversight offices they were sent to. Holman thinks the new information reported by the New York Times, which forms the basis of his recent complaint, will make it more difficult for officials to ignore Bernhardt’s violation.

“If history is any guide, the [designated agency ethics official] may once again ignore the complaint, though the specificity of the evidence should make it harder to do so,” Holman told Sludge. “The Inspector General’s office, on the other hand, is somewhat more independent and so it is unknown what the Inspector General’s office will do with it.”

If neither the Interior Department ethics official, Scott de la Vega, or inspector general, Mary Kendall, act on the new complaint, there is little that Holman or other watchdog groups could do to further elevate the matter through official channels.

“Since the complaints are based on a White House executive order rather than a law, this is as far as I can go in seeking enforcement of the ethics rules,” Holman said. “I have no standing under the executive order to file my own lawsuit. But highlighting the apparent violations by filing such a public complaint may prompt the Senate to raise the issue in confirmation hearings, which could also help push for enforcement of the rules.”

Related: