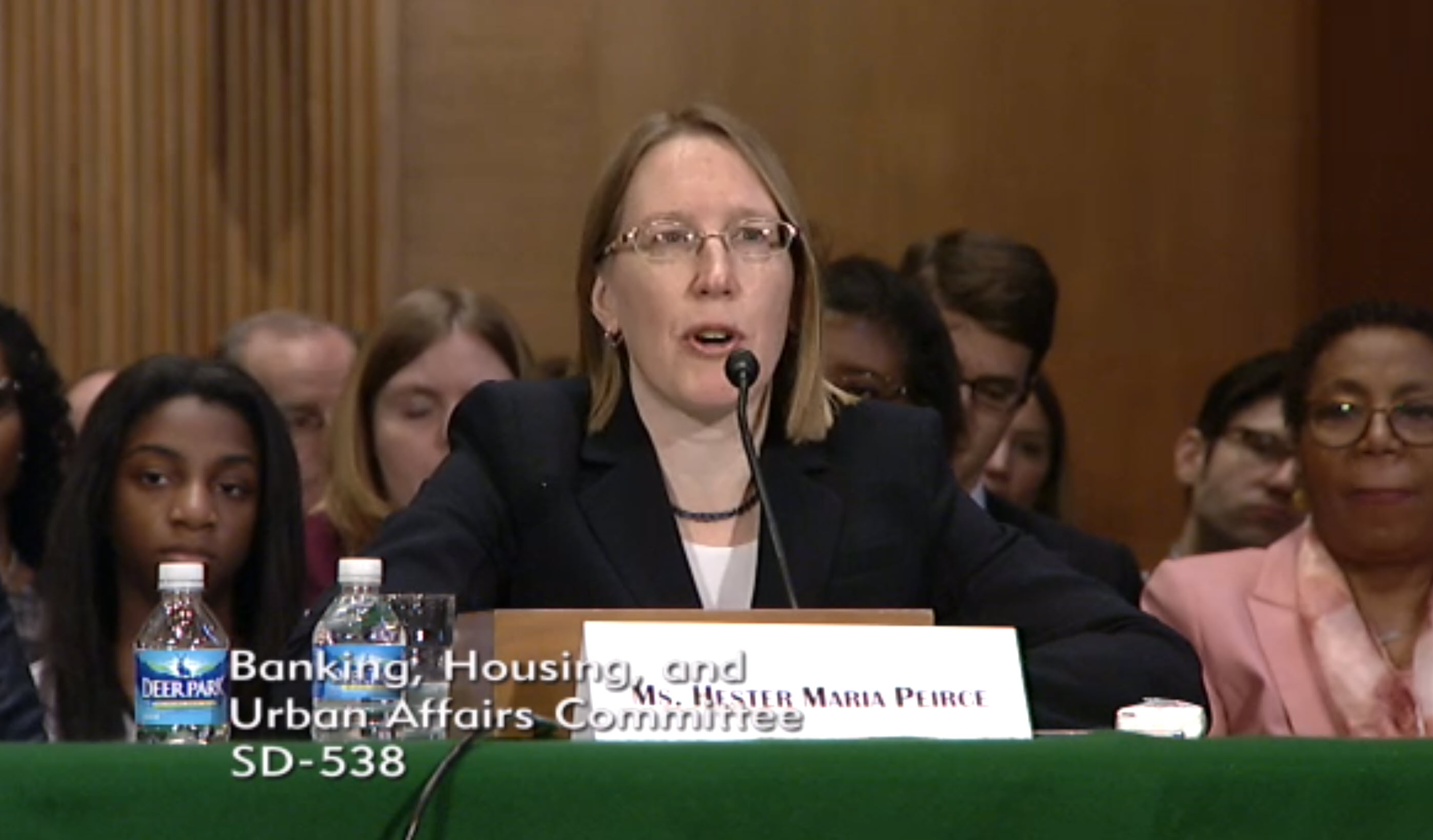

In a Sept. 24 lecture, Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) Commissioner Hester Peirce told University of Michigan law students that if they want to change the world, they should represent corporations.

“Representing corporations also can be a form of public interest law because companies contribute so much to the well-being of society,” she said, according to a transcript released by the SEC on Monday.

“Charitable activities are laudable,” she continued, “but, to find something good, we need not look beyond the core profit-making activities of the corporation.”

What Peirce didn’t tell the students was that her academic career was funded by billionaire industrialist Charles Koch, the libertarian CEO of Koch Industries who has poured enormous amounts of money into politics through his big political network of wealthy, rightwing donors in order to slash regulations and cut taxes. Koch has also donated hundreds of millions of dollars to U.S. colleges and universities, typically funding free-market economics programs.

Before joining the SEC, Peirce was a senior research fellow at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University and director of its Financial Markets Working Group.

No university has received more money from the deep-pocketed Charles Koch Foundation than GMU, a public institution in Virginia. Koch helped found and fund the Mercatus Center, an on-campus free-market think tank, as well as the Institute for Humane Studies, another conservative think tank at the university. Recently, the Koch Foundation donated $10 million in conjunction with a mystery donor, represented by Leonard Leo of the Federalist Society, to fund GMU’s law school, renaming it after the late Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia and creating a number of new professorships.

Rather than laud corporate lawyers for their contribution to public service, we need SEC commissioners who seek to fulfill the agency’s primary goal of protecting investors from predatory corporate practices.

Remington A. Gregg, Public Citizen

Peirce went on to talk about regulators’ role, which she said should be kept to a minimum in favor of people in the private sector who are “closest to the relevant facts.” Her argument inverts the typical interpretation of public interest by claiming that, from within government, lawyers can aid the public by assisting for-profit corporations.

“That is not to say that those of you who end up working for the SEC—as I hope some of you will—should feel left out of the public interest discussion. You too will contribute to the public interest by helping, albeit indirectly, to ensure that resources and people go to the entities best able to put them to work for society’s well-being.”

Government watchdog Public Citizens sees things differently.

“There is nothing wrong with representing corporations, but to insist that corporate lawyers are fulfilling a public service is laughable since their objective is to protect corporations from liability, find clever ways for them to get out of complying with enforcement laws, and generally provide Wall Street with an hospitable regulatory environment that will reap their clients large profits,” said Remington A. Gregg, Counsel for Civil Justice and Consumer Rights at Public Citizen.

“The fact that an SEC commissioner is comfortable making such an assertion shows that we have learned little as a society from the impact that weak laws and regulations had in contributing to the Great Recession,” Gregg said. “Rather than laud corporate lawyers for their contribution to public service, we need SEC commissioners who seek to fulfill the agency’s primary goal of protecting investors from predatory corporate practices.”

Former New York Times labor reporter Steven Greenhouse tweeted on Tuesday, “Would someone please tell Hester Peirce — and Donald Trump — that we want watchdogs, not lapdogs on the SEC. We want bulldogs, not poodles.”

Recasting the Free Market

Peirce’s use of the term “well-being” in a free-market context is something that the Koch Foundation has been doing in recent years. Some new university centers, which in previous years may have been called a “center for political economy” or “center for the study of free enterprise,” are using a “well-being” framework to describe cuts to social programs and a market free from regulation.

In a rebrand detailed by New Yorker reporter and Koch expert Jane Mayer, the Koch brothers enlisted a public relations firm to improve their image. And at a secret 2014 gathering, longtime Koch operative Richard Fink suggested a new way to frame free-market economics, as rising income inequality and corporate corruption had become a great concern among many Americans, and the Koch brothers had become reviled among liberals as greedy businessmen and enormous GOP donors. The Koch network needed to describe free-market economics as an apolitical and altruistic to improve people’s lives: “a movement for well-being.”

“The network should make the case that free markets forged a path to happiness, whereas big government led to tyranny, Fascism, and even Nazism,” wrote Mayer.

At Wake Forest University in North Carolina, the Koch Foundation funded and help found the Eudaimonia Institute. The center states that eudaimonia is “Aristotle’s word for ‘well-being,’ ‘happiness,’ or ‘flourishing.’ Free-market economist James Otteson, also a fellow and former director of the school’s BB&T Center for the Study of Capitalism, directs the Eudaimonia Institute. At the 2014 gathering, Otteson said that the term “well-being” would be a “game-changer.”

The Charles Koch Foundation is giving out “foundations of well-being” grants. The Charles Koch Institute has a Well-Being Initiative and hosted its first Well-Being Forum in 2014. And the Koch-funded political nonprofit, Americans for Prosperity, has a Bridge to Wellbeing program.

The Structure of Social Change

GMU and other higher education institutions are at the center of Koch’s 1970s plan to turn American society against taxes and regulations. With his longtime ally Richard Fink, Koch created the “Structure of Social Change” roughly four decades ago. Fink asserted that higher education can produce the “intellectual raw materials” for think tanks to repackage into policy ideas. Then advocacy groups can turn these ideas into simplified proposals that the public can digest and then rally those people to push for policy change.

By funding university economic departments, think tanks, and outside political groups such as Americans for Prosperity, Koch and his wealthy allies created a rightwing policy juggernaut. And Koch’s political network often recruits graduates of these free-market programs for their advocacy network, while other graduate sometimes remain in the education system as professors.

Now, in the case of Peirce and others, Koch-funded university scholars and think-tank fellows are leapfrogging right government policy and regulatory positions. Others have joined the White House. And with his political donor network funding conservative Republican campaigns, Koch has helped numerous allies win positions in Congress. In addition, congressional staffers have been known to become Koch Industries lobbyists, and vice-versa.

As his social change plan was in motion, Koch made enormous profits from his industrial conglomerate, Koch Industries, which he ran with his brother, David, until the latter recently stepped down due to health issues. Today, according to Forbes, Charles Koch, the richest person in New York City, is worth $54.2 billion.

Koch’s business, which includes oil refining, chemical production and synthetic materials manufacturing, and has racked up numerous environmental, labor, workplace safety and employment discrimination violations, costing the company $737 million since 2000, according to Good Jobs First. Without government regulations, Koch would be free to pollute the environment or endanger workers without penalty.

Peirce is by no means the only Antonin Scalia Law School alum to recently join the Republican administration.

- Noemi Rao, currently Trump’s “regulatory czar”—the administrator of the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs within the Office of Management and Budget—is on leave from her professorship at the law school, where she founded the Center for the Study of the Administrative State.

- Nathan Alexander Sales, a former GMU law professor and corporate lawyer, is now coordinator for counterterrorism at the State Department.

- Jonathan F. Mitchell, nominated for but not yet confirmed as chairman of the Administrative Conference of the United States, an independent agency, is a former GMU law professor.

Still more Mercatus Center and Institute for Humane Studies scholars and faculty work in the Trump administration. Peirce’s comments come at a time when dozens of lawyers from the nation’s biggest corporate law firms have scored appointments within the Donald Trump administration. Many of these officials “either previously represented companies with business before the government, or worked in the same field they now oversee,” writes Alan Zibel, author of a Public Citizen report released in March.