Last month, Oakland voters made their city the first in California to adopt a program of public campaign financing for elections known as “Democracy Dollars.” Advocates in other California cities say the Oakland measure’s success could help spur similar efforts in their areas, toward leveling the playing field in local elections.

Oakland’s democracy dollars program was approved on Election Day as the centerpiece of Measure W, a ballot measure that passed with 74% of city voters in favor. The measure will establish a program that sends four $25 vouchers to every Oakland registered voter, which voters can then donate to qualifying candidates for city office and school board. The candidates would then redeem the vouchers for public campaign funding, starting in the 2024 cycle.

The democracy dollars program in Oakland is based on the first-of-its-kind voucher program in Seattle, which was used for the third time last year in the city’s municipal elections. By distributing vouchers to all voters, the program aims both to counteract the influence of wealthy donors and broaden participation in local politics, helping more of the city’s voters back candidates in their communities and enabling candidates to run who don’t already have networks of wealthy backers to fund their campaigns. A study of the latest Seattle election, which included the first race for mayor with democracy vouchers in play, found that it helped the donor pool become the most diverse yet in terms of race, age, and income.

In addition to creating the democracy dollars option for candidates and a system to transparently display the voucher program’s data, Measure W—titled the Oakland Fair Elections Act—strengthened campaign finance rules on other fronts: the campaign contribution maximum in city races was lowered from $900 to $600, campaign ads will be required to list their top three contributors, and watchdogs at the independent Public Ethics Commission received a funding boost to hire staff.

If you don’t have personal wealth or networks of wealthy donors, and you have a long history of community leadership and grassroots support, you can run a viable campaign for city council using the Democracy Dollars program. And that’s a game changer.

Jonathan Mehta Stein, California Common Cause

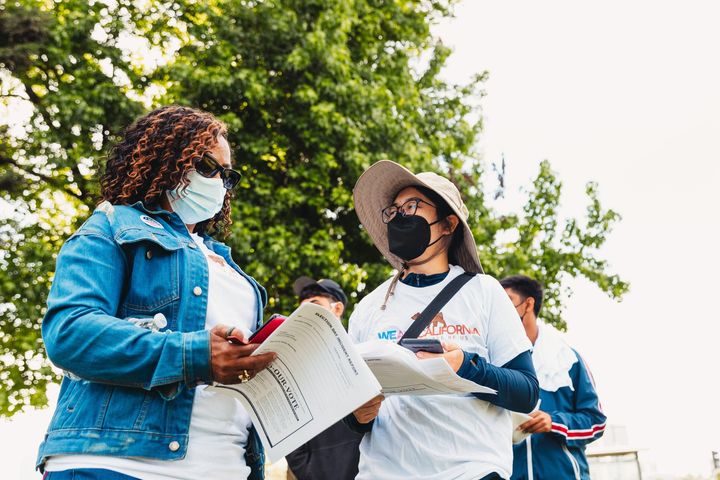

The Oakland measure was supported by a coalition of groups that included the nonprofits California Common Cause, the League of Women Voters of Oakland, and the grassroots group Oakland Rising, part of the Bay Rising alliance of community organizations. The Fair Elections campaign was joined by a broad list of endorsing organizations including the ACLU of Northern California, the Advancing Justice – Asian Law Caucus, and the multi-racial group Causa Justa :: Just Cause, led by low-income San Francisco and Oakland residents.

The breadth of the Yes on W campaign’s endorsers helped propel the measure to a resounding approval, Jonathan Mehta Stein, the executive director of California Common Cause, told Sludge.

“We spent four years building a coalition that included not just the democracy reform and good government groups, but also groups rooted in Oakland’s communities, specifically its communities of color and working-class communities, and civil rights organizations that care about this from a racial equity perspective,” Stein said. “That combination of groups meant we had a diversity of perspectives at the table, which was helpful, but also we could reach a diversity of city council members, no matter their perspective.”

The Oakland City Council advanced Measure W in July to appear on the November ballot in a unanimous vote of members present.

Stein said, “By the time the election rolled around, we had a coalition of trusted groups with names people recognized—we had the Sierra Club, we had labor unions, we had the Alameda County Democratic Party. We had community organizing groups door-knocking, so while we didn’t have big money, we had people power.”

“This is an attempt to empower all people with a real emphasis on the families, neighborhoods, and communities that are currently left out and ignored by the political system,” Stein said. “If you don’t have personal wealth or networks of wealthy donors, and you have a long history of community leadership and grassroots support, you can run a viable campaign for city council using the Democracy Dollars program. And that’s a game changer.”

Oakland candidates who opt-in to the democracy dollars program must first qualify by reaching a threshold of eligible small-dollar contributions, then are required to limit their total campaign spending, cap their household’s out-of-pocket campaign spending, and participate in public debates, among other things.

At the launch of the Yes on W campaign in March, the Berkeley-based civic tech nonprofit MapLight released a report on its findings that since 2014, just half of Oakland candidates’ fundraising came from city residents, with money coming in from outside residents and donations from trade associations and PACs making up a sizable share. Of Oaklanders’ donations, some 45% of campaign contributions came from the city’s richest and whitest neighborhoods, a disproportionate amount compared with zip codes that had a lower median income below $60,000.

“For too long, our elections have been funded by wealthy special interests and out-of-state donors,” said liz suk, executive director of Oakland Rising Action. “In recent years, over half of money raised by city council and school board candidates was from people who don’t even live in Oakland. Measure W will empower Oaklanders to have a bigger influence, and ensure candidates are listening to voters rather than special interests.

“This victory was many years in the making and it happened because we all built a strong coalition and organized not only with voters, but also with city council members to qualify the measure for the ballot,” suk said. “Oakland Rising and Oakland Rising Action’s public education work throughout 2022 built momentum with the nearly 8,000 new and infrequent voters with whom we held conversations.”

Common Cause’s Stein says that while the U.S. Supreme Court has proven itself to be unfriendly territory for money in politics reformers, the Oakland coalition’s success shows a path for similar campaigns.

“My hope is that Oakland represents a light in that darkness—not just a win, but an emphatic margin of victory, one that can show other jurisdictions that this is possible,” Stein said. “We’ve already begun conversations with coalitions in other cities and our Oakland coalition would be thrilled to help anyone bring this to their city, school board, county, or state.”

Public campaign financing advocates in other California cities were eyeing the results of the Democracy Dollars vote in the Bay Area. In San Diego, the Voters’ Voice Initiative is sharing educational materials about the results from Seattle’s voucher system in increasing candidate choice and small-donor participation. Amy Tobia, a local leader with the reform group Represent San Diego, told Sludge, “We’re excited to see how significant the support was for Measure W and their success will be a boost for our efforts locally.”

In Los Angeles, in the wake of turmoil after council members were taped engaged in racist conversation, the group Los Angeles for Democracy Vouchers is calling not only for campaign finance reform, but also for redistricting reform and expanding the city council. A voucher option modeled on Seattle’s program is central to its goal of improving the city’s representation. Group co-founder Tom Latkowski told Sludge, “We’ve been targeting a 2024 ballot initiative, but we’re even more excited now, looking at what the new council coming into office looks like. We’re eager to work with them on initiatives.”

Oakland voters approved all 10 measures that appeared on their ballots in November, including an overhaul of city tax rates and an $850 million infrastructure bond.

Measure W’s accompanying provisions underscore how its authors want Democracy Dollars to encourage face-to-face discussions with voters where they live, not just at high-dollar fundraisers. “Pairing a Democracy Dollars program with a lowering of the campaign contribution limit is a no-brainer, because they’re both geared at the same idea: getting candidates to raise smaller dollar contributions from a wider base of people,” Stein said.

The Oakland measure’s new requirements that campaign advertisers list their top three donors in their ads will boost public transparency about spending in elections. “It’s an attempt to address the fact that no matter how transformative Democracy Dollars are, we still have to contend with money in politics because of the Roberts Supreme Court,” Stein said.

The latest Oakland elections saw their share of shadowy spending by Bay Area business interests. In the race for Oakland mayor, a former city council member, Ignacio De La Fuente, received a large number of first-place votes in the ranked-choice voting system. The volunteer group No Coal in Oakland tracked how hedge fund founder Jonathan Brooks, whose firm has interest in a coal terminal site, donated at least $550,000 to an independent expenditure committee backing De La Fuente’s bid. The committee, named Californians for Safer Streets Supporting Ignacio De La Fuente, also received $50,000 from the company of real estate developer Phil Tagami, who has been proposing to build the coal export terminal. In the last round of ranked-choice voting tabulation, Oakland City Council President Pro Tem Sheng Thao edged out District 6 Councilmember Loren Taylor to become mayor-elect.

Oakland voters will have a chance to hear directly from more city office seekers as the program rolls out. Candidates who opt in to the democracy dollars program commit to take part in public debates—at least five for mayor, three for other offices. In a press statement after the measure was approved, Ashley Morris of the ACLU of Northern California said, “By requiring candidates to participate in public debates, Oaklanders will have more opportunity to develop a better understanding of the candidates’ plans for the issues that impact their lives—like housing, community safety, and public schools—and allocate their democracy dollars vouchers accordingly.”

Oakland’s wasn’t the only successful ballot measure for a public campaign financing program last month: voters in Portland, Maine approved by almost two-thirds a Clean Elections measure that will expand the state’s public funding option to qualified city candidates, as proposed through a city Charter Commission process.