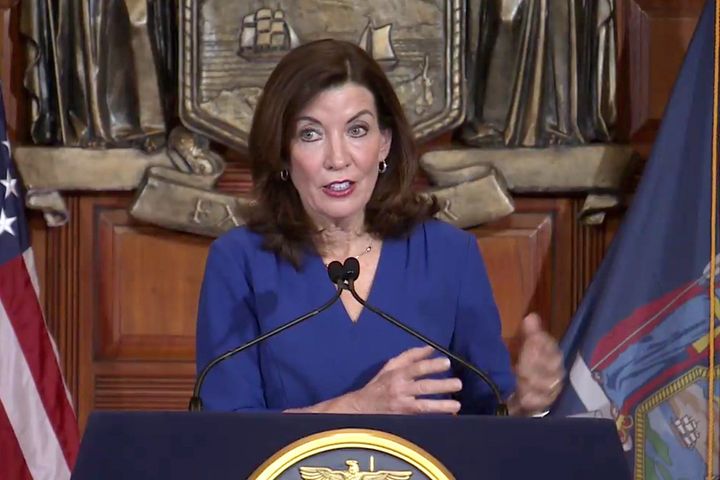

As part of the enormous New York state budget finalized late last week, Gov. Kathy Hochul and legislators came to an agreement to dissolve the state’s dysfunctional ethics board, the Joint Commission on Public Ethics (JCOPE), and replace it with a new entity.

Good government groups including Common Cause New York and the League of Women Voters of New York had warned before the deal was finalized that the agreement on the commission being floated in the Albany press suffered from the same major flaw as JCOPE: that its members would not be independent of the politicians who would appoint them. The ethics reform “box,” they said in a joint statement, would not be “checked,” in the wake of years of corruption scandals in state government and the resignation of disgraced New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo.

Now, the good government groups are out with a letter that slams the new Commission on Ethics and Lobbying in Government (CELG) as “fatally flawed,” because elected officials will continue to directly select and appoint their own ethics commissioners. The details of the new commission’s composition and selection process, passed as part of the Education, Labor and Family Assistance bill, were finalized in negotiations behind closed doors, with ethics experts unable to see the bill language as it came together in the $220 billion state budget package.

In her first State of the State address in January, Hochul called to eliminate JCOPE, which was created in 2011 to ensure compliance with ethics and lobbying laws. Watchdog groups had called the body “toothless and useless,” with its 14 members appointed by the governor and legislative leaders. The commission was seen by good government organizations and others as dominated by allies of Cuomo, who through his second term as governor had never been probed by JCOPE, even though several of his close associates were arrested on corruption charges.

In July 2020, JCOPE approved Cuomo’s $5.1 million book deal, a project that was revealed to have been produced through a vast misuse of state resources, according to a sweeping New York State Assembly report released in November 2021. The Assembly’s investigation concluded that Cuomo had used state resources for personal profit. In addition, the FBI investigated the Cuomo administration’s hiding of nursing home data on over 4,100 deaths from the coronavirus, a finding in the Assembly’s report that was later corroborated by an audit from the state comptroller.

Last August, New York Attorney General Letitia James released findings of her office that Cuomo sexually harassed at least 11 women. Those findings were also included in the Assembly’s report, which concluded there existed grounds for Cuomo’s impeachment. In December, JCOPE ordered the former governor to surrender millions of dollars in profits from his book in a 12-1 decision that Cuomo has challenged with a lawsuit.

The new CELG will form an 11-member body: three nominated by the governor, two by the Senate majority leader, two by the Assembly speaker, one by the Assembly minority leader, one by the Senate minority leader, one by the attorney general, and one by the comptroller. The nominees would then be confirmed or denied by an “independent review committee” composed of law school deans. According to the budget bill text, the review committee shall convene as needed or as requested by the elected officials, and vote to approve or deny the commission’s nominees within 30 days. The committee will be made up of American Bar Association-accredited New York state law school deans, interim deans, or a designated associate dean, and the group is charged with publishing its review procedure on its website. Once approved, CELG commissioners will appoint their panel’s chair through a majority vote. Unlike JCOPE, CELG will be subject to state Open Meetings Laws and Freedom of Information Law under language agreed to in the budget.

“The commission continues the fatal flaw of JCOPE, which is direct appointments by elected officials,” said Rachael Fauss, senior research analyst of the nonprofit Reinvent Albany. “When watchdogs talk about independence, it is not a system where elected officials are directly appointing the people who regulate them. Unfortunately, that’s what this commission is.” More than half a dozen editorials from around the state criticized the design of Hochul’s plan in the lead-up to its announcement.

After a year of high-profile scandals, New York lawmakers continued a history of secrecy when writing the plan for the new commission, the full text of which was not released to the public or to rank-and-file legislators until April 8 as the state budget was under pressure for being past its April 1 due date.

“The devil is always in the details and this proposal was about public accountability, but the public couldn’t even read it,” said Fauss. “Because ethics reform was still on the negotiating table alongside big complicated issues like bail reform that meant it was going to be in ‘the big ugly’ budget deal and legislators wouldn’t be able to vote on it as a standalone item. It appeared next to education funding or programs in legislators’ districts.”

In their discussions with lawmakers about a better plan for the new commission over the past month, Fauss said, good government groups raised the model of independent legislative redistricting processes in states like California or cities like Austin, Texas, where members of the public can apply to serve, without being nominated by politicians. Several government ethics commissions—for instance, in Alaska and Rhode Island—have members of the public serve, Fauss told Sludge. The New York reform groups’ most recent proposal called for a seven-member selection committee appointed by the leaders of the legislature and the three statewide elected officials, with layers of transparency and prohibitions on who can serve and with members of the public able to apply to be ethics commissioners.

In California’s case, a 2008 ballot initiative created the Citizens Redistricting Commission, an independent agency composed of 14 citizens—five Democrats, five Republicans, and four that are not affiliated with either of those two parties, from varied ethnic backgrounds and geographic locations in the state—who become candidates to serve through an application and selection process run by the state auditor. Under the Voters First Act, the law first passed in 2008, the Commission draws the boundaries of California’s congressional, Senate, Assembly and Board of Equalization electoral districts. Notwithstanding any court challenges, the district maps the commission crafts apply until the next decennial redistricting.

A dozen Democratic state lawmakers including Sen. Alessandra Biaggi sent a letter on April 5 to Hochul supporting the New York groups’ seven-member selection committee plan and pushing back against CELG’s appointment procedures. “Asking law school deans to rubber stamp appointments by elected officials is also not sufficient to provide public confidence,” the letter says.

Among the civic and good-government groups active in calling for a better process and structure for overhauling JCOPE was the Sexual Harassment Working Group, a volunteer collective of nine former New York State Legislature staffers who reported sexual harassment while working for the state. Erica Vladimer, an attorney, policy analyst, and group co-founder who in 2018 accused former state Sen. Jeff Klein of sexual misconduct, a charge Klein denied, told Sludge that her group is involved in the push for a truly independent state ethics body because JCOPE had not protected former state staffers who had experienced harassment, assault, or retaliation from elected or appointed officials. “Four years later, I still have no resolution to holding Jeff Klein accountable,” Vladimer said. In a hearing last year, Klein’s attorney argued that JCOPE does not have jurisdiction in the case. The watchdog groups’ letter flags that the budget law does not extend the CELG’s authority to matters under the New York State Human Rights Law, which defines sexual harassment in the workplace. “This kind of ambiguity leaves victims incredibly vulnerable,” Vladimer said. “Leaders are supposed to be held accountable for abuse of power, and that includes harming their staff.”

After JCOPE’s often-criticized record in handling sexual harassment cases, Vladimer said, she was deeply concerned that the new ethics commission similarly fails to ensure the independence of its members: “It is not only going to keep staff vulnerable, it will not only send a very clear dangerous message to staffers that they don’t matter, but we could be stuck with this for years to come.”

This post was updated to clarify that the five public members of Alaska’s nine-member Select Committee on Legislative Ethics are ratified by two-thirds of the full legislature. Of the Rhode Island Ethics Commission’s nine members, all public volunteers, four are appointed directly by the governor and five are appointed by the governor from lists of nominees submitted by legislative leaders.