Mike Bloomberg’s run for the Democratic presidential nomination might have seemed short-lived, but its lasting legacy may be the discovery of a loophole that lets rich individuals obliterate the legal limits on campaign contributions.

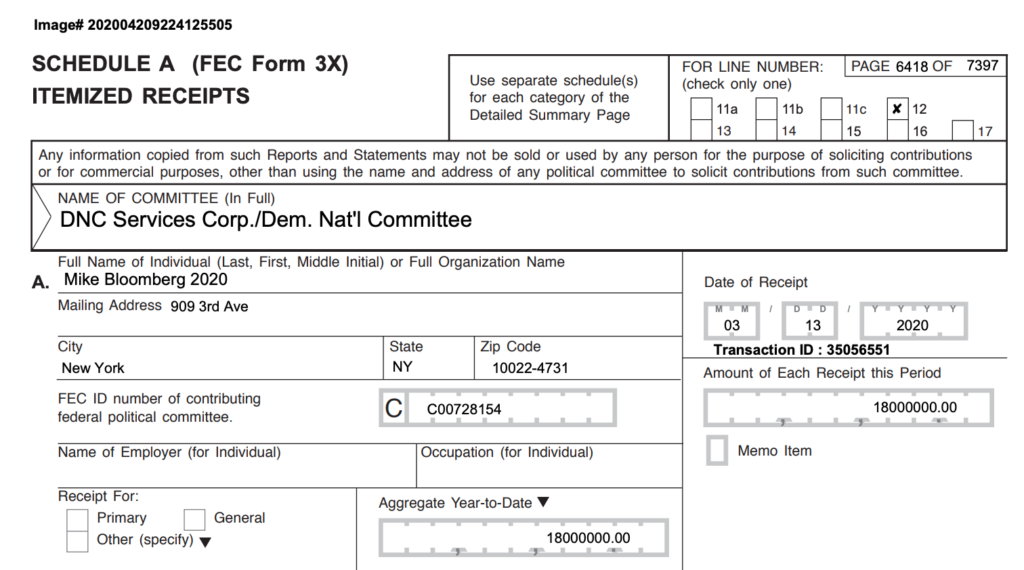

On March 13, after suspending his presidential campaign, the former New York City mayor transferred $18 million from his campaign to the Democratic National Committee to back its organizing push in 12 battleground states.

The DNC’s windfall far exceeds the $35,500 maximum legal contribution an individual can give to a national party committee in the 2019-2020 election cycle, and government ethics watchdogs immediately flagged it as pushing the boundaries of campaign finance law.

“It looks like Bloomberg and his lawyers exploited a loophole no one knew existed,” Brendan Fischer, director of federal reform at the nonpartisan ethics group Campaign Legal Center, told Sludge on Wednesday. “This transaction is certainly concerning to us, and the loophole exploited is one the Federal Election Commission should close.”

The legal justification for the transfer comes down to a quirk of FEC reporting practice, Fischer explained in a March 26 blog post. The billionaire’s campaign was self-funded, tracing back to the Supreme Court’s 1976 decision in Buckley v. Valeo that approved unlimited spending out of a candidate’s own pocket.

The FEC, for its part, has instructed candidates to report money they spend on their own campaigns on the contributions section of campaign finance filings rather than the expenditures section—and federal law states that “a contribution accepted by a candidate” may be transferred without limit to a party.

“Where this becomes a problem is it intersects with the allowance created by SCOTUS to spend unlimited personal funds supporting a campaign, and the two together created a loophole that’s never been exploited to this degree,” Fischer said. “Some other self-funded candidates in the past had transferred leftover funds to a political party, but nothing like this,” he said of CLC’s research into any precedents.

“When one billionaire can give $18 million to a political party, that billionaire is going to have a significant amount of influence over the party,” Fischer said. “The ‘Bloomberg loophole’ has angered groups and voters across the political spectrum, but there does seem to be bipartisan support for preventing another billionaire from routing tens of millions to another political party.”

On April 9, conservative group Citizens United, which is primarily known for vastly ramping-up money in politics through the 2010 Supreme Court ruling that helped establish super PACs, filed a petition to the FEC on the Bloomberg loophole. The letter from Citizens United’s president David Bossie requested the FEC close the loophole in order to prevent people from evading certain spending limits by launching phony political campaigns and then self-funding. Fischer says the CLC is likely to file in support of that comment.

Any action on the Bloomberg loophole falls to the FEC as the nation’s top elections watchdog—an agency that effectively shut down on Aug. 31, 2018 when it lost its quorum of at least four of six commissioners, in the midst of the midterms. On May 19, 2020, the Republican-controlled Senate confirmed Texas attorney Trey Trainor as the fourth commissioner, where he joins a Democrat, a Republican, and an independent who usually votes with Democratic commissioners.

One issue behind the lengthy confirmation process for Trainor, a Trump loyalist and former lawyer for the Texas Republican Party, was that Senate Republicans discarded the norm of nominating commissioners in bipartisan pairs—his eventual vote was along party lines, 49-43. Good-government groups including Campaign Legal Center, Common Cause, End Citizens United, and Issue One opposed Trainor’s confirmation because of his lax views on regulating political spending and opposition to increased transparency.

[Update, Friday June 5, 4pm ET: the FEC sent out a press release announcing that Trey Trainor was sworn in today.]

While the FEC is a step closer to reopening after Trainor’s confirmation vote, the agency will not officially reach quorum until he is sworn in privately. Judith Ingram, press officer for the FEC, told Sludge over email that the FEC did not have a schedule for Trainor’s swearing-in. “Once that happens, the Commission can operate with a quorum, and the scheduling of meetings and other Commission business can be determined,” Ingram wrote, anticipating a press release being sent out. As of this writing, Trainor is still not officially displayed as a commissioner on the FEC website’s leadership page, over two weeks after his Senate confirmation vote.

When the FEC fell below quorum, responsive rule-making on election matters fell by the wayside. In March of 2017, Democrat Ann Ravel resigned from her spot as commissioner, citing gridlock around the agency’s lack of action on “dark money” regulation and campaign finance enforcement under the Trump administration. Republican Lee Goodman resigned in February 2018 to rejoin Wiley Rein LLP, a lobbying firm that advertises itself as “Wired Into Washington” and earned nearly $3.5 million last year from lobbying for clients such as AT&T, Verizon, Century Aluminum, and steel company Nucor Corporation. Republican Matthew Peterson resigned in August 2018, the move that dropped the FEC below quorum, to join law firm Holtzman Vogel Josefiak Torchinsky, which specializes in advising PACs and “dark money” nonprofits on election spending.

Recently, another former wealthy candidate decided to test the Bloomberg loophole: Shaun McCutcheon, an Alabama businessperson and former presidential candidate for the Libertarian Party, asked the FEC in a May 29 letter if he could transfer $50,000—in excess of the $35,500 limit—to the party. McCutcheon was the plaintiff in a momentous 2014 Supreme Court decision against the FEC that struck down aggregate campaign contribution limits by a vote of 5-4.

When the FEC does recommence meetings, it faces not just the question of the Bloomberg loophole but a backlog of some 350 pending cases. Asked about the potential timeline, the CLC’s Fischer said, “Any FEC rule-making action or action pertaining to rule-making won’t be finalized before the election, none of the pending rule-makings are close enough.” Depending on the FEC’s schedule and catch-up work, this leaves the possibility that Congress could pass a law closing the Bloomberg loophole—unlikely this year, with Sen. Majority Leader Mitch McConnell’s control of the upper chamber.

Michael Beckel, research director for cross-partisan political reform group Issue One, told Sludge of the importance of a functioning FEC in backing up the spirit of campaign finance laws, along with the letter.

“It is crucial that the FEC work to swiftly reduce the backlog of cases on its enforcement docket.” Beckel said. “When enforcement cases linger for years, it sends the signal that others, too, can bend or break the rules and get away with it. If the FEC does not take action to close the Bloomberg loophole, it’s likely we’ll see other wealthy candidates replicate the maneuver in the future.”

Transferring his leftover campaign account in March was not the only large donation made by Bloomberg to the Democratic party as he joined the presidential field. On Nov. 19, 2019, days before Bloomberg launched his presidential campaign on Nov. 24, he made three donations of $106,500 to three DNC accounts (one for the national convention, one for legal support, and one for the party headquarters building), as well as an $800,000 contribution to the Democratic Grassroots Victory Fund, which was split up and allocated to state Democratic parties. (Bloomberg moved one additional donation of $35,500 to the DNC that day, part of a package with the Democratic Grassroots Victory Fund and financial trader Daniel Tierney.)

The gifts marked Bloomberg’s first donation to the DNC since 1998, and in late January, DNC Chair Tom Perez nominated two Bloomberg campaign surrogates to the 2020 Democratic National Convention Rules Committee. In February, to accommodate the Bloomberg campaign, Perez unilaterally dropped the party’s individual donation requirement to be on stage in the Feb. 19 presidential debate in Las Vegas.

Among the long list of issues for the soon-to-be-reconstituted FEC to take up ahead of the 2020 elections, Beckel highlighted the problem of lack of transparency in online political ads. An Issue One report in November 2019 identified a host of dark money issues with digital ads, which are not required to disclose the same info to the FEC as if they were radio ads.

The CLC’s Fischer flags some important complaints pending from 2015 that the FEC still hasn’t closed. For example, in one pay-for-play case involving the largest private prison contractor, “GEO Group, a federal contractor, gave $225,000 through a wholly-owned subsidiary to a super PAC supporting then-candidate Donald Trump—in our view, that violates the law, and implicates the reasons it’s on the books in the first place. We’ve seen hundreds of millions of dollars in new contracts following six figure donations to Trump’s super PAC, as the FEC sat on these complaints for nearly four years now.”

Trevor Potter, the president of Campaign Legal Center and a former chairman of the FEC appointed to the agency in 1991 by President George H.W. Bush, drew attention to the findings of a Nov. 2019 poll commissioned by CLC. “71 percent of voters across partisan lines said that they would like the FEC to take a more active role in enforcing campaign finance laws,” Potter told Sludge. “With Trainor confirmed as the new FEC commissioner, it is almost guaranteed that instead of taking a more active role, the agency will continue to fail to protect and inform voters.”

This story was updated to include above comment from former FEC Chair Trevor Potter, and with a link to the press release announcing that in the afternoon after this story was published, the FEC officially swore in Trey Trainor as commissioner.