In Illinois, the general election for governor features two billionaires, one Democrat and one Republican, engaging in a self-funded face-off. Across Lake Michigan, in the Wolverine State’s Democratic gubernatorial primary, unusual election spending has also occurred, including a shady outside spending group, connections to a major health insurer, and an $8 million mystery.

Establishment favorite Gretchen Whitmer, whose father is the former CEO of Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan, has taken an assist from her father’s company. Blue Cross executives asked employees to donate to Whitmer’s campaign and held a fundraiser for the candidate on March 7, netting her nearly $145,000 in campaign contributions. The company said its political action committee doesn’t endorse candidates, but “it periodically provides its members an opportunity to directly support candidates for elective office.” Four PAC leaders signed the event invitation, which the Whitmer campaign sent out to Blue Cross PAC members whose addresses the PAC provided to the campaign. No in-kind donation attributed to Blue Cross is listed in Whitmer’s most recent campaign finance report.

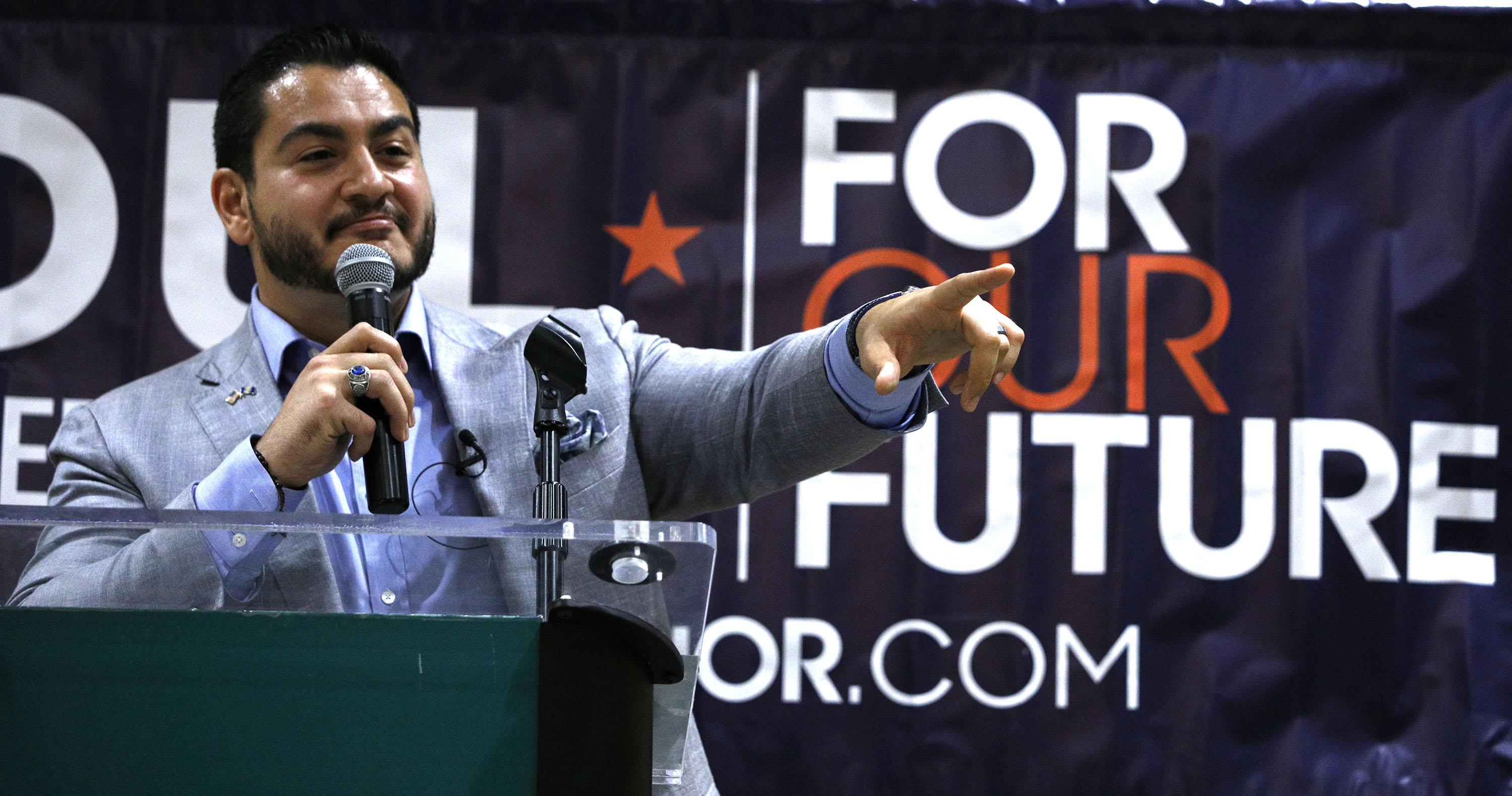

Another Democratic candidate, the progressive doctor and Medicare-for-All supporter Abdul El-Sayed, called Whitmer out on Twitter in late July, after the Whitmer campaign’s latest campaign finance filing became public.

On March 7th, at a closed-door lunchtime fundraiser at Firebird Tavern in Detroit, Senator @GretchenWhitmer sold out the 600,000 Michiganders who do not have access to healthcare for $144,710 in campaign donations from Blue Cross Blue Shield.

— Abdul El-Sayed (@AbdulElSayed) July 27, 2018

That's 24 cents per Michigander.

The other Democrat in the race, chemical testing entrepreneur Shri Thanedar, says he supports a single-payer health care system.

As the former state Senate minority leader, Whitmer worked with Republicans to expand Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act. But if her health care policies at all align with Blue Cross’, she’s unlikely to push for Medicare-for-All or another single-payer system. Such a system would essentially replace Blue Cross and other health insurers with health care directly paid for by the government.

Single-payer “is not realistic in Michigan at this moment,” she told Crain’s in January.

Adam Joseph, communications director of Abdul for Michigan, told Sludge that “[Whitmer’s] outside group, Build a Better Michigan, is nothing but a shell for dark money PACs, unlimited money from corporate CEOs, and corporations like Blue Cross Blue Shield who have interest in a Whitmer-led Michigan. She has held closed-door fundraisers with Blue Cross Blue Shield—raising $144,710 dollars—and as a result, she stands against single-payer healthcare and has yet to release a healthcare plan.”

The Whitmer campaign did not respond to a request for comment.

Untraceable Super PAC Donations

Build a Better Michigan (BBM), a Section 527 political organization established in March that has booked at least $1.8 million in TV ads supporting Whitmer, said that a glitch in its electronic reporting process caused it to mail its most recent financial disclosure to the Internal Revenue Service. That process could have left voters in the dark about its funders for up to ten weeks, after the primary election. After public pressure, BBM unveiled its donors, showing donations from unions, Michigan corporations, individuals and the national political group, Emily’s List.

The organization accepted two large contributions from organizations that have scarce, if any, public records. Progressive Advocacy Trust gave the biggest donation to BBM, $300,000, and the Philip A. Hart Democratic Club donated $250,000.

Progressive Advocacy Trust is the “admin account” of the Ingham County Democratic Party, according to BBM’s IRS filing. That’s the Michigan region that Whitmer represented in the state Senate for 14 years. According to the the Progressive Caucus of Mid Michigan, Ingham County Democrats were told their group would not make an endorsement in the party’s gubernatorial primary. “Nobody in the party has admitted to knowing where the money came from,” wrote the group on Facebook.

In the most recent filing on record, covering the period from Nov. 29, 2016 through the end of 2017, the Ingham County Democratic Executive Committee reported receiving only $27,000 in contributions. Crain’s found that the independent expenditure committee of the Michigan Pipe Trades Association gave $250,000 to Progressive Advocacy Trust, through that group’s federal campaign finance report.

The Philip A. Hart Democratic Club’s president told Crain’s that its contribution to BBM came from “an account different from the federal PAC,” which at the time of the donation had far less than that amount on hand, according to its June Federal Election Commission disclosure.

Some, including El-Sayed, have speculated that Blue Cross may have used either of these entities to funnel money to the political nonprofit without a paper trail. Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan’s spokesperson Helen Stojic declined to answer Sludge’s questions about the governor’s race, including whether the company had donated to the Philip A. Hart Democratic Club or Progressive Advocacy Trust. “We don’t want to publicly comment on” the race, she said.

Whitmer’s father, former Blue Cross CEO Richard Whitmer, gave $10,000 to the super PAC.

A Cozy Relationship with an Outside Spending Group

Whitmer’s father isn’t the only link she has to this outside spending group. Most, if not all, paid employees of BBM appear to be Whitmer campaign staffers: Alaina Pemberton, who lists herself as the Whitmer campaign’s deputy finance director on LinkedIn; Carolina Pratt, Whitmer’s finance director and deputy campaign manager; Carli Fettig, compliance assistant for the campaign; Jess Isler, campaign finance intern for the campaign; Joe Popek, compliance director; Bri Sauer, whose Twitter bio says “Team @gretchenwhitmer”; and Josh Neyhart, ho appears to work for the campaign as well. It’s possible these BBM employees left the campaign before joining BBM, but their public profiles don’t indicate this.

BBM appears to be using one of its director’s companies as a contractor. The committee made two payments in May and June totaling $5,000 to Burton Strategies of Lansing, Michigan. Mark Burton, Whitmer’s former chief of staff and the super PAC’s director and president, is CEO of Burton Strategies.

Whitmer is featured in BBM’s latest ad, something she’s only allowed to do if the group doesn’t explicitly tell voters whom to vote for. At the federal level, 527 groups may not legally coordinate with candidates, but in Michigan, 527 groups and other organizations that don’t engage in express advocacy for candidates fall outside of state campaign finance reporting requirements and may coordinate.

While BBM is required to disclose its donors to the Internal Revenue Service, the Philip A. Hart Democratic Club and the Progressive Advocacy Trust don’t have to do so, Craig Mauger, executive director of the Michigan Campaign Finance Network, told Sludge. Mauger thinks these two groups are 527 organizations connected to political action committees or party organizations. A loophole in federal tax law exempts 527 groups that are connected to a PAC or a state or local political party from disclosing their donors to the IRS, assuming they’ll have state reporting requirements. But because Michigan state law doesn’t cover 527s, these groups can spend money on politics without ever revealing their funding sources.

Corporate Cash

While Blue Cross’s PAC hasn’t directly donated to Whitmer, her campaign has accepted a lot of money from the PACs of other corporations, including Centene Corporation, HNTB Holdings, lobbying firm Midwest Strategy Group, and multiple law firm PACs. El-Sayed, by contrast, has rejected corporate PAC money altogether, although he has received some individual contributions from executives.

“We believe in a politics for the people and by the people,” said Joseph, El-Sayed’s communications director. “That’s why we don’t take a dime from corporate PACs or dark money groups. It’s why people can be confident that an El-Sayed administration won’t be bought.”

Thanedar has rejected corporate PAC money as well, saying he’s the most progressive candidate in the race. But in 2008, he donated to the campaign of Republican Sen. John McCain of Arizona, and eight years later attended a rally for Florida GOP Sen. Marco Rubio. These facts, along with reports that he considered running as a Republican, have made people question just how progressive Thanedar really is. A HuffPost feature on Thanadar characterized him as a “wealthy opportunist” posing as a progressive.

Thanedar is allegedly self-funding his campaign. A “late campaign finance report” filed on July 31 shows he has given nearly $12 million to his campaign, but expenditure reports only detail $2.9 million in spending. That leaves no small sum, $8 million, unaccounted for just days prior to the election.