Thurgood Marshall Jr., the older son of the renowned civil rights leader and Supreme Court justice of the same name, donates thousands annually to a political action committee run by CoreCivic, the second largest private prison company in the United States.

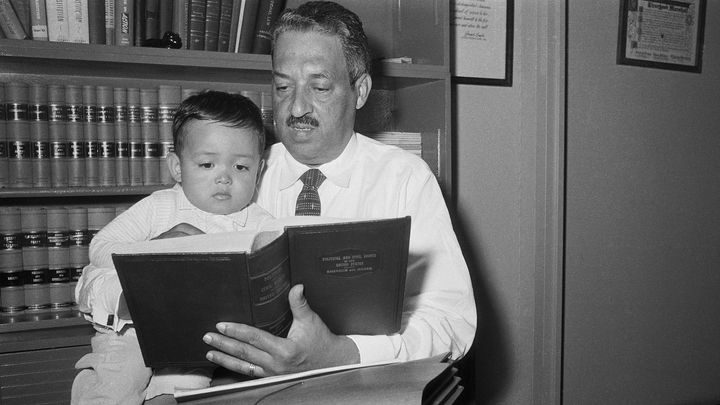

The grandson of a slave, Thurgood Marshall was the first president of the NAACP Legal Defense fund and the first African-American justice on the Supreme Court. An ardent and radical civil rights advocate, his arguments won African Americans the right to vote in primaries in the South and, at least in law, worked to end segregation.

His son, Marshall Jr. joined the board of CoreCivic Inc., formerly known as the Corrections Corporation of America, in 2002 after serving as Assistant to the President and White House Cabinet Secretary in the Clinton White House. In 2016, he received $221,000 in compensation for working on the CoreCivic board.

CoreCivic has drawn attention in the news for profiting from mass incarceration and detaining immigrants on behalf of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE).

The United States is the world’s leader in mass incarceration, with a total of 2.3 million prisoners as of 2018. In 2015. U.S. private prisons incarcerated 8 percent of the total prison population —126,272 people—a population that tends to be young, Black, and Brown.

“What the company does, from a broad perspective, is profit from the criminal justice system,” said Alex Friedmann, associate director of the Human Rights Defense Center. “Since they rebranded themselves as a real estate investment trust back in 2013, they’ve marketed themselves as a real estate company, but their real estate primarily consists of correctional facilities.”

Since 2004, Marshall Jr. has donated $62,500 to CoreCivic’s political action committee, which has spent 90 percent of its campaign contributions this cycle to elect Republican legislators.

What about the other 10 percent? Four Democrats have also received money from CoreCivic this cycle. In the House, CoreCivic’s PAC has contributed to Democrats Tim Ryan of Ohio, a Presidential-hopeful who challenged Nancy Pelosi for Speaker of the House and Rep. Henry Cuellar of Texas, one of the 18 House Democrats who joined the Republican party in voting for a GOP resolution in support of ICE. In the Senate they have given to Democrats Martin Heinrich of New Mexico, who said he donated the money to charitable causes and Sen. Jon Tester of Montana.

“I’m afraid that when politicians accept donations from these companies, they also are then pushing for policies that house migrants in remote locations like Folkston, Georgia, far from families, legal counsel, better laws, and so on,” said Prerna Lal, an immigration attorney and founder of DreamActivist, an online advocacy network led by undocumented youth.

The first CoreCivic facility was established in 1984 in a converted Houston motel to hold immigration detainees for the Immigration and Naturalization Service. In 2015, it looked as if CoreCivic’s long standing business model was in trouble; Stocks plummeted when the Obama administration announced it would phase out federal contracts with private prison companies. But in response to the Trump administration’s reversal of that policy, stocks for CoreCivic and GEO Group (the largest private prison company in the U.S) soared.

In 2017, 52 percent of CoreCivic’s income was based on contracts with ICE, the United States Marshals Service, and the Federal Bureau of Prisons. According to the most recent data available, as of 2015, 62 percent of immigration detention beds were operated by private prisons like CoreCivic, but there is significant evidence that percentage has increased substantially. Between 2017 and so far in 2018, CoreCivic has received more than $250 million in funding from ICE.

“I [worked with] an asylum seeker who sought asylum at the California border, but was sent to a remote location in Georgia where he is very likely to lose and be deported due to the refugee roulette,” said Lal. “The system of immigrant detention harms due process, and stacks the odds against us.”

CoreCivic, which earns close to two billion dollars annually, also spent $840,000 lobbying federal legislators in 2017. Among other policy asks, they advocated for “increased funding for inmate work programs,” which civil rights groups like the ACLU have criticised as ”exploitative.” Beyond policy papers and federally required lobbying statements, it’s hard to say what CoreCivic lobbyists advocate for.

“The companies will argue at great length that they do nothing to lobby about length in sentences, or about who’s getting locked up or how long. But you pretty much have to take them at their word for that,” Friedmann said. “Presumably they’re getting something. Because if I pay a buck at a donut shop, I want a donut. If they’re paying 1.5 million for lobbying, I’m pretty sure they’re getting something for that.”

When Marshall Jr. was nominated to the Board of Directors for CoreCivic, a contributing factor to his candidacy was that we would provide a ”contribution to the Board’s cultural diversity.” CoreCivic’s Board includes several other high-profile figures whose backgrounds seem contradictory as representatives for private prisons. Charles L. Overby, a fierce advocate for free-press and the former Chairman of Washington D.C’s Newseum, is a board member of CoreCivic, which in the past employed an “aggressive media strategy” to counter journalists.

Marshall Jr. declined to comment on why he is on the board of a private prison company.

Friedmann said that years ago, he spoke with Marshall Jr., asking asking why he would join a company that doesn’t seem to represent his father’s legacy. His response to Friedmann was this: to make the company better.

“Of course, it’s nice of him to get a large stipend for doing that and thousands of shares of stock. Years later I asked him, how is the company better,” said Friedmann. “And he didn’t really have a response to that.“