Lockheed Martin is preparing to offer Japan a stealth fighter jet based on the F-22 Raptor design that is currently banned from being exported under U.S. law. The deal would have to be approved by the Trump administration, and observers are viewing the administration’s pending decision on the matter as a barometer on President Trump’s promise to streamline the country’s process for selling weapons to allies. But the fate of the deal could be impacted even more by the Pentagon’s top official for East Asia, who for nearly a decade has advocated for exporting the technology to Japan and has close ties to a Lockheed Martin sales coordinator in East Asia.

Emails obtained by Sludge through a Freedom of Information Act request show a friendly exchange between Randy Schriver, Assistant Secretary of Defense for Asian and Pacific Security Affairs, and Samuel Mun, a regional coordinator for Lockheed Martin in East Asia. Schriver and Mun previously worked together at Project 2049 Institute, an East Asia policy think tank that Schriver used to head up and where Mun was a research assistant. Reports published by Project 2049 regularly argued for increased foreign military sales to Japan and Lockheed Martin is one of the think tank’s funders.

The two are close enough that Schriver felt comfortable making an off-color joke to Mun from his work email. Later in the exchange, Schriver expressed his desire to bring Mun into a government position after his stint at Lockheed.

“The defense trade world is full of a revolving door of former military, former defense-industrial leaders, and others in think tank world who are pro arms trade,” Jeff Abramson, senior fellow at the Arms Control Association, told Sludge. “It doesn’t immediately disqualify them—they often know a great deal and have a great amount of expertise. But the patterns are there such that a lot of these deals are being made and promoted amongst friends.”

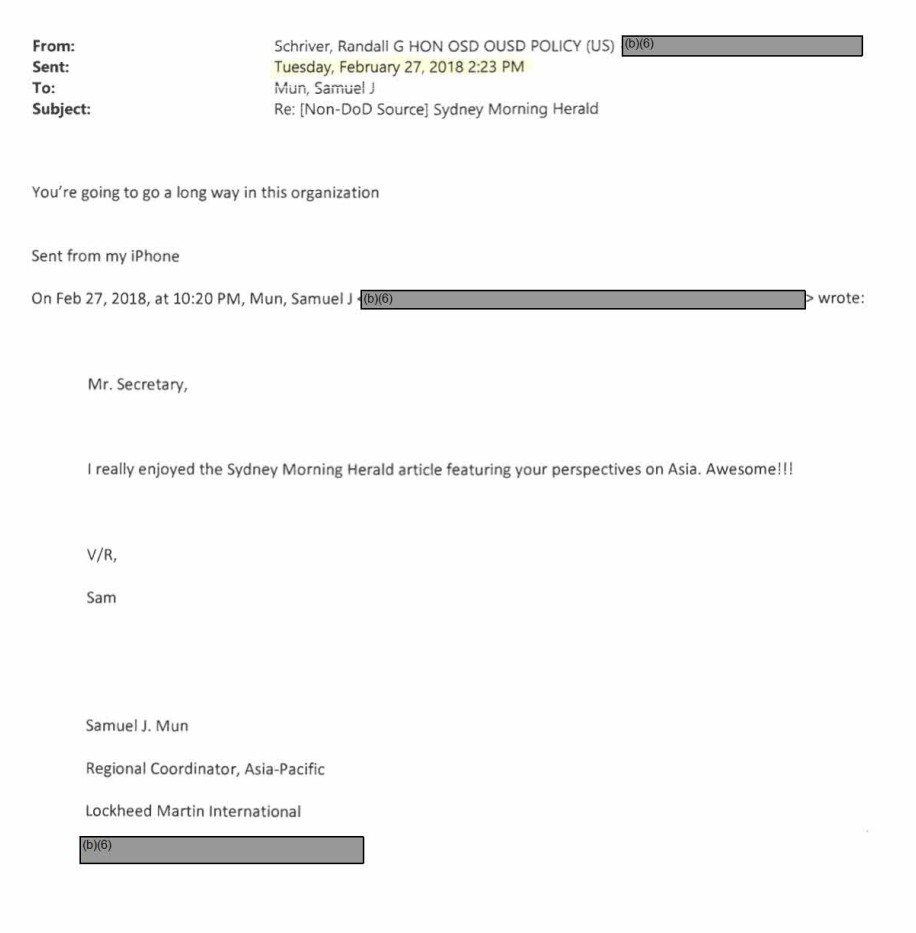

One email shows Mun praising an interview Schriver held in the Australian press. Schriver replied to Mun: “You’re going to go a long way in this organization.”

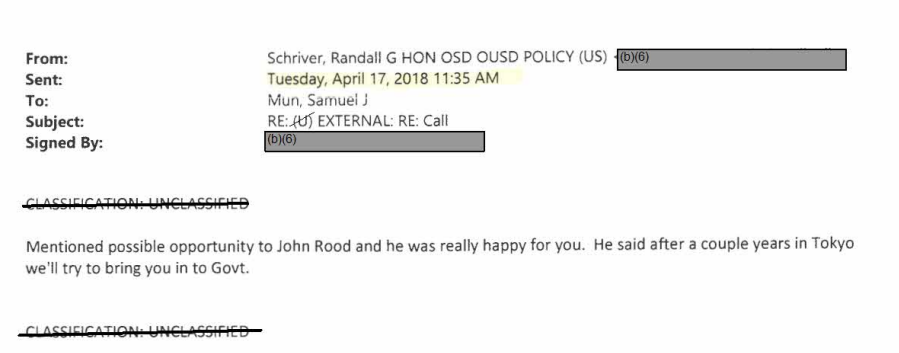

Later, Schriver tells Mun that he talked with Undersecretary of Defense for Policy John Rood about bringing Mun into a government position within a couple of years. Rood is a former senior vice president at Lockheed, where he oversaw international sales. At Schriver’s request, Mun sends Schriver his resume, which Schriver then forwards to Rood.

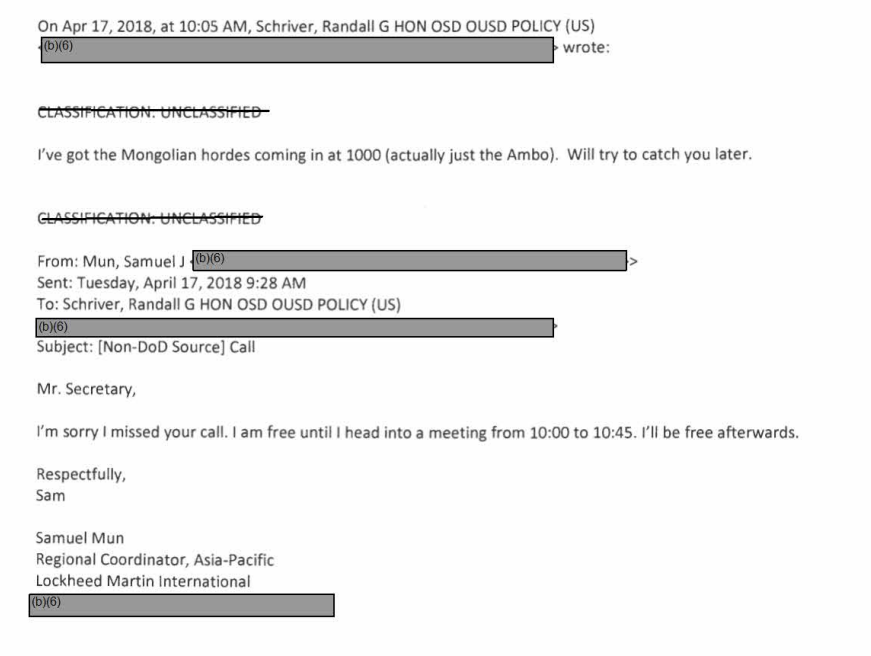

At one point, when Mun and Schriver are trying to find time for a call, Schriver replies that he is unable to take a call at a certain time because the has “the Mongolian hordes coming in at 1000 (actually just the Ambo) [Ambassador].” Schriver was likely referring to a meeting with the Mongolian ambassador, in preparation for the trilateral meeting held between Mongolia, the United States, and Japan the following week. (Update: Schriver’s schedule, obtained through a follow-up FOIA request by Sludge, confirmed that he met with the Mongolian Ambassador that day.)

The Defense Department did not respond to Sludge’s questions about whether there are concerns about the close relationship between Schriver and Mun. Lockheed Martin responded that Mun does not work directly on the F-22 export ban.

“Lockheed Martin hired Sam Mun about two years ago, before this administration began,” wrote William Phelps, a spokesman for Lockheed, in an email to Sludge. “U.S. government policy issues are not part of his portfolio, and he has not worked on topics related to the F-22 export ban.”

A Special Export Exception for Lockheed and Japan?

Reuters reported in April that Lockheed Martin is preparing to offer a stealth fighter for sale to Japan, using a combination of components from the F-35 and the export-banned F-22. Such a fighter would likely use the F-22’s twin engine airframe, with upgraded electronics systems from the more recent F-35. The F-22, which entered the U.S. combat fleet in 2005, was designed to give the U.S. Air Force an edge in air-to-air combat for the foreseeable future. For that reason, Congress banned the fighter from ever being exported in 1998, before it even entered the fleet.

President Trump has made increasing U.S. weapons sales a priority for his administration. Under the president’s initiative launched this year, the economic benefits of a deal are given increased weight, whereas under previous administrations the human rights impact of a deal was considered a priority. Trump has met directly with Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe in order to expedite arms sales to the country. But beyond the president’s own inclinations on the matter, any major weapons deal still legally needs to be approved by the Defense and State Departments.

The DoD’s decision will be largely informed by Schriver, as the new top official for East Asia defense policy. After a decade in private consulting and the think tank world, Schriver was confirmed in December, 2017, as Assistant Secretary of Defense for Asian and Pacific Security Affairs. One of the primary duties of his office is to advise the Secretary of Defense on foreign military sales to strategic allies in his region.

Before assuming his post in the Pentagon, Schriver led Project 2049 Institute, a D.C.-based think tank that has since 2008 published reports detailing what it perceives to be the strategic threat China poses to U.S. military and economic interests. Experts employed and published by Project 2049 have argued for aggressively ramping up foreign military sales to China’s neighbors such as Japan and Taiwan and encouraged policies that in some cases risk provoking military conflict with China.

While heading up Project 2049, Schriver also worked as a consultant for Armitage International, the consulting firm of former Deputy Secretary of State Richard Armitage. His clients at Armitage included several defense contractors and, notably, the government of Japan. Normally, Schriver would be barred from working in a government position on policy matters that affect a former client, but he received an ethics waiver from the Trump administration allowing him to work on matters relating to the Japanese government, such as offering the country the export-banned F-22.

Mun, like Schriver, simultaneously worked for both the Project 2049 think tank and Armitage’s consulting firm.

Since Schriver was appointed to his new position in the Pentagon, Project 2049 has redesigned its website and several old reports and policy memos were never reuploaded or intentionally removed. Project 2049 did not respond to questions about why those memos were on an older version of its website, but not the new iteration.

One such memo, published in former President Obama’s first month in office, made recommendations for how to “jump start the process of alliance enhancement” with Japan. The key recommendation in that memo, written by Schriver and Project 2049 executive director Mark Stokes, is to offer the F-22 to Japan.

That memo reads in part: “Of all the possible steps an Obama Administration may take in the first one hundred days, a decision to announce intent to make F-22 Raptors available for export to Japan could be the most significant and consequential of all.”

Published in January 2009, this now-deleted memo shows Schriver’s history of advocating for exporting the F-22 to Japan for more than nine years. In his new role as the principal policy advisor on foreign military sales to East Asia, he is now in a position to achieve that goal, to the benefit of his former consulting client.

Concerns over the F-22 Sale

If the proposed F-22/F-35 hybrid sale were to go through, it could create cascading problems for the U.S. military.

The F-35 program has been plagued for years by cost overruns and the total estimated cost of the fleet jumped 7 percent last year. An internal Defense Department analysis from December found that the U.S. Air Force may have to decrease its order of F-35s by up to a third, if costs cannot be reined in.

If a version of the F-22 were made available for export, it could very quickly exacerbate those problems. Many U.S. allies are purchasers of the F-35 with orders waiting to be filled. But those allies might prefer an air superiority fighter based on the F-22. And if they switch their orders from the F-35 to the F-22, costs for the F-35 could skyrocket as the per-unit cost increases as the total order number decreases.

“Quite a few countries within the F-35 program would much rather have the F-22, particularly Australia and Japan but also Canada,” Justin Bronk, Airpower and Technology Research Fellow at the Royal United Services Institute in the United Kingdom, tells Sludge. “The prospect of partners pulling out or trying to switch out of the F-35 program for something else is a serious concern because production costs and unit costs and support costs would skyrocket because the economies of scale would go out the window.”

Furthermore, there are concerns that a new hybrid F-22/F-35, which Bronk calls a “super-Raptor,” would outclass anything in the current U.S. combat fleet in the air superiority role.

“America is extremely cautious about exporting anything that is its gold standard,” says Bronk. “But if you were to successfully take the best aspects of the F-35 and put them into in effect a modernized F-22 airframe you would have something that is superior to the U.S.’s finest air superiority aircraft.”