Today, the U.S. Census Bureau released 2020 census data that will be used by states to redraw voting districts, kicking off a months-long redistricting process and likely many legal challenges to maps.

In the last cycle of redistricting in 2011, the district maps drawn in Wisconsin by Republicans made the state the most gerrymandered in the nation, according to biennial reports from the Electoral Integrity Project (EIP), an independent academic project. The partisan tilt of Wisconsin districts was so extreme that in 2018, when Democratic candidates for the State Assembly won 53% of the votes cast statewide, a margin of 205,000 votes, they only received 36% of the Assembly seats.

This year, the Republican-controlled Wisconsin State Legislature will again draw the district maps, but the decennial process is sure to play out differently with a Democratic governor, Tony Evers, who is likely to veto Republican-drawn maps. A veto would send the redistricting process to the state’s courts to draw the maps, as was the case in the previous four decades before the 2011 process.

Democratic lawmakers reintroduced legislation in May that would ban partisan gerrymandering and establish an independent redistricting process with greater public transparency, with maps drawn by the nonpartisan Wisconsin Legislative Reference Bureau and overseen by a citizens panel, a model already in use by Iowa and Michigan. Last week, sponsors Sen. Jeff Smith and Rep. Deb Andraca sent a letter requesting a public hearing on the bills to the chair of the Senate Committee on Government Operations, Sen. Duey Stroebel, and the chair of the Assembly Committee on State Affairs, Rep. Rob Swearingen. Their legislation, which their letter says could “avoid costly litigation for the state taxpayers,” has three Republican state representatives as cosponsors.

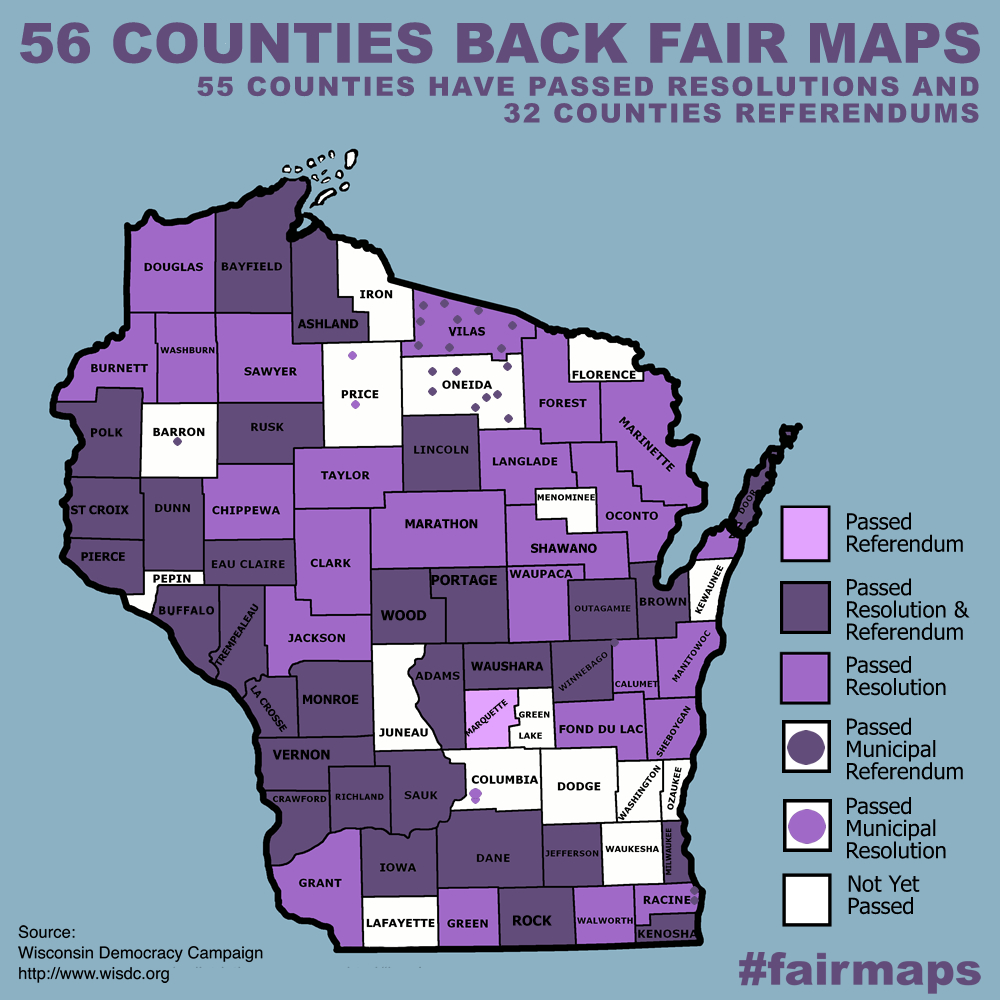

Over the past several years, a grassroots campaign in Wisconsin has pushed back against partisan gerrymandering by demonstrating public support for fair maps. As of April, 56 of Wisconsin’s 72 counties have passed measures endorsing nonpartisan redistricting—including 32 counties through referendums, and 55 county boards with resolutions—representing over 83% of the state’s population. The Wisconsin Fair Maps Coalition, composed of state groups that have advocated for years on gerrymandering reform including Common Cause Wisconsin, the Fair Elections Project, and the League of Women Voters of Wisconsin, has worked to encourage local passage of the nonpartisan resolution, spread by its two dozen coalition partners.

In his 2020 State of the State Address, Gov. Evers announced the creation of the People’s Maps Commission, composed of “doctors, librarians, and teachers, not politicians, lobbyists, or elected officials,” charged with developing fair maps. While its maps are not binding on the legislature, the nonpartisan commission will submit its results to state Senate and Assembly leaders—and potentially show its work to courts—as examples of maps that are, as Evers stated the purpose, “free from partisan bias and partisan advantage.” The commission is chaired by Dr. Christopher Ford, an emergency physician in Milwaukee, and the first meeting of the nine commissioners was held Oct. 1.

Ahead of the commission’s first public hearings in Wisconsin’s eight congressional districts, the Fair Maps Coalition stepped up efforts to solicit public input on how impartial maps can be drawn, Organizing Director Carlene Bechen told Sludge. Bechen said the coalition hosted about two dozen panel discussions of people who lived in each district talking about how gerrymandering had impacted their communities over the past 10 years and sharing information about how to submit testimony to the commission.

“The level of engagement with the People’s Maps Commission shows the undeniable desire on the part of the people of the state of Wisconsin to have a fair, open, honest process that includes public input on how our voting districts are drawn,” Bechen said.

The Most Partisan District Lines Ever

The 2011 Republican maps, calculated in secret in a “map room” at a GOP-aligned law firm near the State Capitol, were so extreme in their partisan tilt in favor of Republicans that they were struck down by a federal court in 2016. The Supreme Court finally ruled in 2019 in Gill v. Whitford that federal courts do not have the power to decide cases on partisan gerrymandering, squashing the legal battle.

In an EIP report released in Dec. 2016, Wisconsin was ranked at the very bottom—50th out of the 50 states and the District of Columbia—in an electoral integrity index composed of 11 categories like election laws and voting process. Wisconsin’s district boundaries were rated as just eight out of a possible 100, the second-lowest score in the nation at the time, just behind North Carolina at seven. By EIP’s 2018 report, Wisconsin’s district boundaries score had fallen to only three out of 100—lower than any jurisdiction EIP had ever analyzed.

Heading into the 2016 elections, state political reporters determined that Republicans had a 25-seat structural advantage in the state’s 99 Assembly seats due to the way lines were drawn. In 2016, Republicans garnered 52% of votes cast, about 161,000 more votes than Democratic candidates, yet took 65% of the Assembly seats. In some districts, this meant a five- to 10-point GOP advantage.

State data released after the 2018 elections showed that Republicans had increased their built-in advantage to 64 of the 99 Assembly districts compared to the Democrats’ 35, almost exactly the 63-36 margin Republicans held after votes were counted. Democrats would need a 10-point statewide edge to take a majority in the Assembly, according to an analysis using data from researchers at Marquette University. In the 2020 elections, Democratic candidates won 45.5% of Assembly votes statewide to the Republicans’ 54.5%, but got just 38% of Assembly seats. The Assembly now stands at 61 Republicans to 38 Democrats, with the State Senate at 21 Republicans to 12 Democrats.

A New Tool for Drawing Fair Maps

Last year, groups in the Fair Maps Coalition reached out in their areas to help Wisconsinites create their “community of interest” maps to submit to the commission, encouraging districts that prioritize the commission’s traditional criteria of compactness for fair partisan makeup.

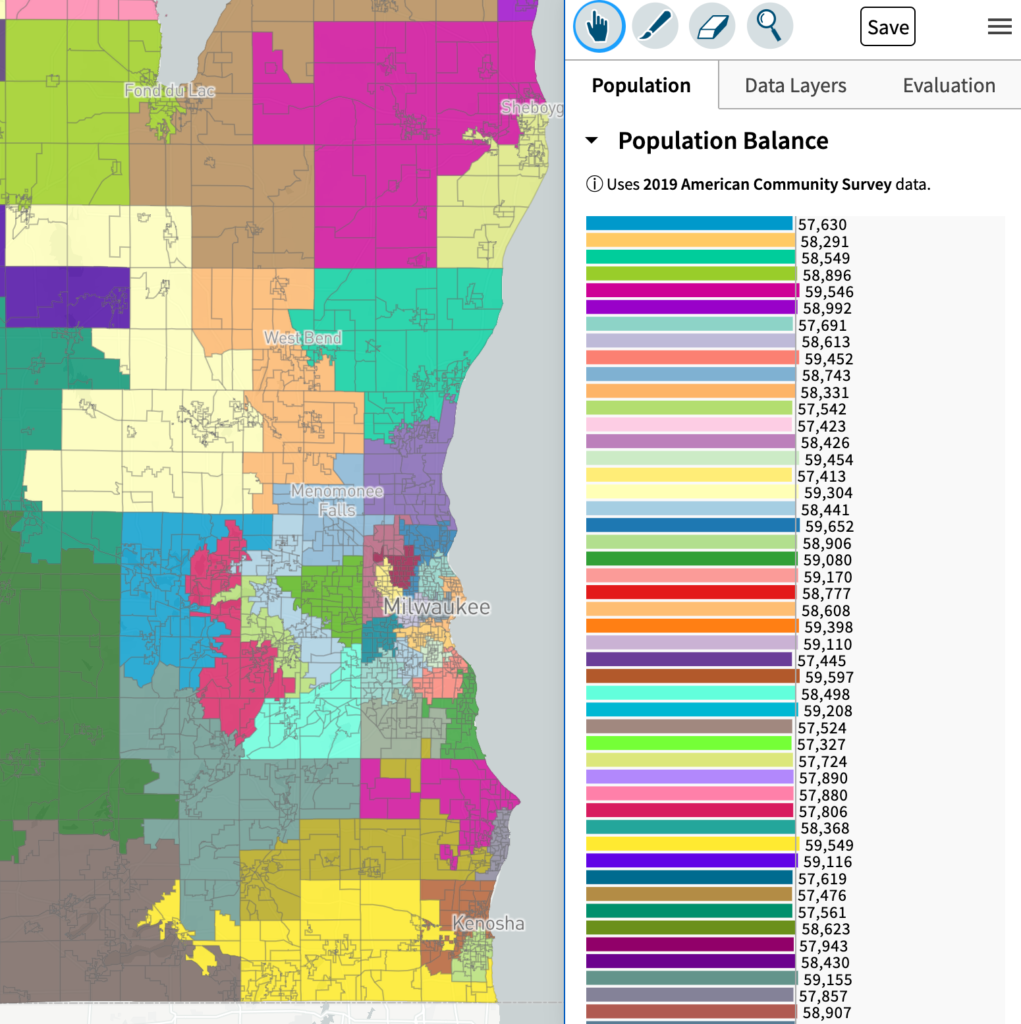

Bechen said the coalition’s efforts received a boost in June with the launch of a new online portal developed by the MGGG Redistricting Lab, a nonpartisan research organization with support from the Jonathan M. Tisch College of Civic Life at Tufts University, that streamlined submission of public maps to the commission. Coalition members the League of Women Voters, Wisconsin Native Vote, and volunteer teams around the state took the lead in holding community trainings on using the free and open-source software, Districtr.

The coalition surpassed its goal of helping to facilitate a total of at least 800 submissions of public maps drawn by Wisconsinites to the People’s Maps commission, Bechen said, with outreach including groups helping people draw maps at “Mappy Hour” events at brew houses. “We’re now at the point in the process where people can give feedback on various plans and say, ‘My neighborhood is still split up,’” Bechen said. “Our job is not over—we’re going to keep people engaged giving real input into how the final product of the People’s Maps Commission turns out.” Individual maps are browsable in an online gallery, with more sample plans collected according to various criteria mentioned by the commission. The commission’s hearings are viewable in videos on its website, along with its written testimony.

At the same time, the Fair Maps Coalition will continue to push for a permanent legislative fix, with the latest nonpartisan redistricting bills stuck in committee. “We’re contacting legislators on a regular basis to say we want a hearing on these bills and that the people of Wisconsin want a nonpartisan process,” Bechen said.

Common Cause Wisconsin and the League of Women Voters spearheaded email campaigns that sent over 6,000 messages to lawmakers, and held parties mailing postcards to voters in districts where the fair maps referendum had passed but legislators were not in support of nonpartisan redistricting, encouraging them to contact their representatives. A lobby day is planned for Sept. 27, the day before the next legislative floor session, Bechen said, either in the state’s capital or online, depending on public health advisories around the coronavirus pandemic.

Of the 56 Wisconsin counties that have passed anti-gerrymandering resolutions, 43 of them voted for Trump over Biden in the 2020 election, and 44 went for Trump in 2016. In addition to the counties that passed fair maps resolutions, the nearly three dozen counties—many of them Republican—that voted for referendums represent nearly 61% of the state’s population. Over the past five years, counties passed the nonbinding call for nonpartisan redistricting with overwhelming majorities.

The Milwaukee-based organization Black Leaders Organizing for Communities (BLOC), founded in the wake of the 2016 election, works to empower the city’s Black residents. BLOC Executive Director Angela Lang says organizers spent months training on redistricting issues alongside the group All On The Line, a national campaign against gerrymandering.

“The last two weeks of July, we had 20 ambassadors knocking doors and over 400 individual conversations about redistricting and we were able to submit 280 community maps and narratives to the People’s Maps Commission,” Lang told Sludge. “We plan to continue to educate the community about the issue as the process continues to play out.”

Renewed Campaign Finance Reform Package

Last week, Democratic lawmakers introduced the “Campaign Integrity” package of seven campaign finance reform bills, building on similar measures introduced in 2017 and seeking to limit large donations while enhancing disclosure of political spending.

The package is supported by the nonprofit and nonpartisan Wisconsin Democracy Campaign (WDC), whose Executive Director Matthew Rothschild said that the package “would correct some of the horrible maneuvers that the Republican-dominated legislature performed in 2015 when they disastrously rewrote campaign finance laws.” There had previously been a $10,000 aggregate limit on an individual’s annual contributions to state and local candidates, but in 2014 the Supreme Court ruled in McCutcheon v. FEC that aggregate limits were unconstitutional. However, Rothschild points out, that doesn’t mean that Wisconsin cannot impose ceilings on donations to political parties and candidates’ campaigns. Currently, Rothschild said, “You could give the limit of $20,000 to the governor and give $20 million to a state party, which could then give it to the governor. It makes a joke of contribution limits.”

The package was introduced by Sens. Melissa Agard and Chris Larson, with Reps. Deb Andraca, Jonathan Brostoff, and Lisa Subeck. Contributions to state PACs, campaigns, and political parties would be capped again at $10,000, and the package would restore the ban on corporate donations to political parties. To increase transparency on the funding behind issue ads, advocacy groups would have to disclose more information about their donors, and people who donate to political candidates would have to disclose their employers, not just their occupation. “In the campaign finance reports, there are 10,000 businesspeople listed, but not which business they work for or what kind of benefits their business gets,” Rothschild said. “We should know who’s paying for the mud that splatters on screens in election time.”

The WDC is also urging its members to contact the Senate and Assembly committee chairs to hold a hearing on the nonpartisan redistricting bills. “When you can’t even get a hearing on a bill that a majority of Wisconsinites support, you’ve got a real problem in our democracy in Wisconsin,” Rothschild said. “It’s shameful there’s no public hearing and vote on it, with three Republican cosponsors and when 56 of 72 counties passed resolutions in favor of it.”