At the New York state budget deadline on April 1, Assembly leaders finally had a clear path to enact something they’ve passed over twenty times since the early 1980’s: a public financing option for state elections.

But instead of taking up the newly Democratic-controlled New York Senate’s provision and including public financing in the budget, Speaker Carl E. Heastie’s Assembly punted—it created a commission to hold a public hearing and produce a public report by December 1 of this year.

With the commission’s nine members still unnamed by legislative leaders and the timeline for its work unclear, a new report from watchdog group Reinvent Albany underscores the need for a more small-donor-focused system among those very Assembly leaders.

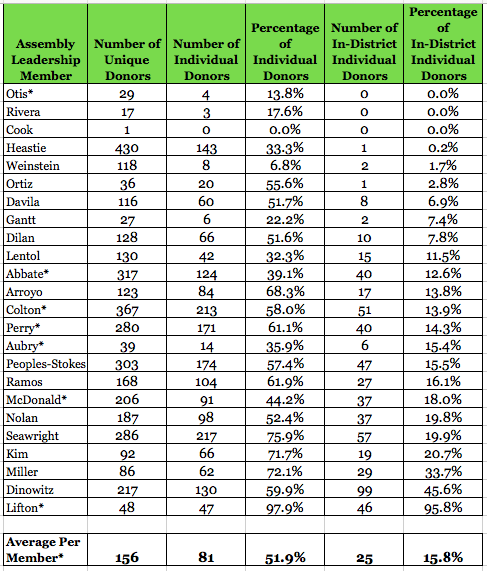

The report released today reveals the extent to which Assembly campaigns are reliant on a few big donors and corporate givers, as opposed to an opt-in public financing system that incentivizes politicians to interact with a larger and more diverse group of small donors. Reinvent Albany found that only 16% of campaign donations to New York Assembly leadership in the last election cycle (2017-18) came from people in their districts—often with under ten actual constituents writing checks.

Reviewing contributions from the New York Open Government portal, about half of the Assembly leaders’ donations came from corporations, trade associations, or labor unions—many of whom have contracts with the state. The report does not factor donations of $99 or less, which are not required to be reported in an itemized fashion by the state.

“Fundraising currently is heavily weighted towards special interests that do business in Albany,” Alex Carmada, a Senior Policy Analyst, told Sludge. Reinvent Albany is part of Fair Elections NY, a coalition which includes over 200 pro-reform groups to limit the influence of big money in state politics.

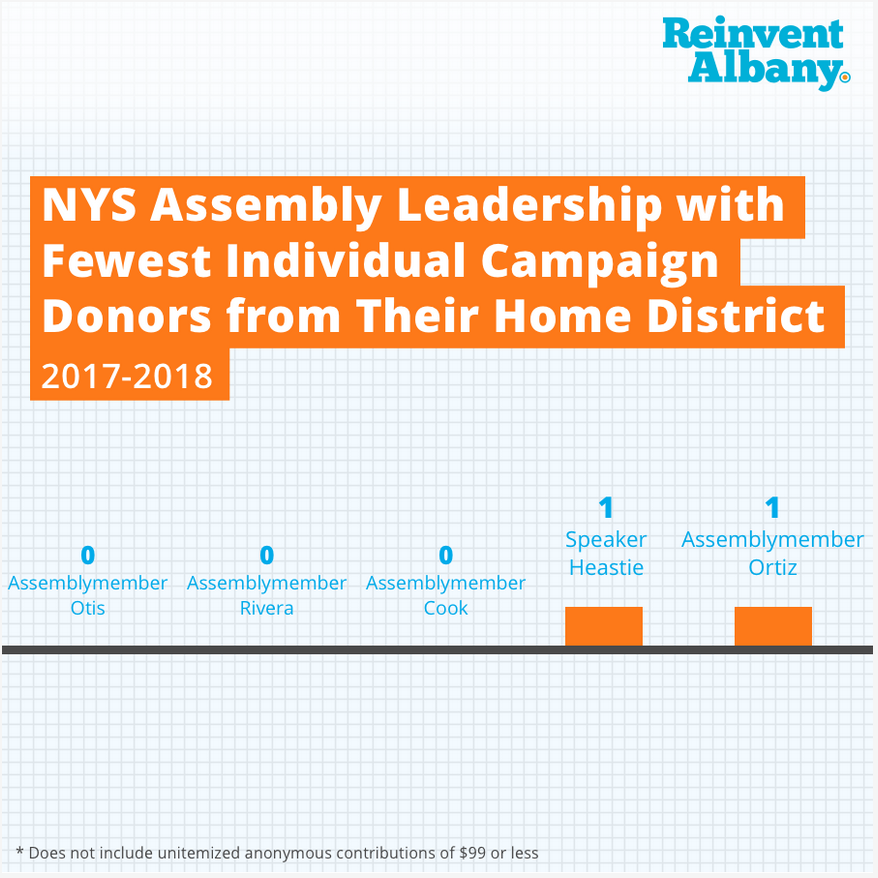

For the 24 Assembly leaders reviewed by Reinvent Albany, the averages were just 81 individual donors and 25 in-district donors. Speaker Heastie’s 430 contributors counted just one donor in his district, while Ways & Means Chair Helene Weinstein of Sheepshead Bay, Brooklyn, had just two in-district donors out of eight total people.

However, the analysis also found that some members received a significant number of donations from people in their district—for example, N. Nick Perry of East Flatbush, Brooklyn, with 40 such donations. According to Reinvent Albany, only 7 of the 24 Assembly leaders had anonymous unitemized contributions.

Reinvent Albany supports a six-to-one public matching system that would encourage wider participation in state elections through the mechanism of incentivizing candidates to hold events and collect checks from small donors, with an emphasis on constituents in their district. Under the current individual contribution limit of $4,700 to an Assembly candidate, 11 max donors could have raised a tad over $50,000; with a 6-to-1 public match, that amount could be raised with close to 150 donations averaging just $50.

“We’re more than a month out from the budget, and Gov. Cuomo and the legislature haven’t appointed the commission members yet,” said Carmada. “The Assembly needs to show the commission’s importance—the Senate and Assembly and Governor need to follow through, and especially appoint the pivotal ninth member to ensure the commission creates a strong public financing system by December 1st.”

With 88 of the Assembly’s 106 Democratic members on the record in support of the public financing package, and the new class of progressive Democratic Senators pushing Gov. Cuomo to profess his own support early this year, it seemed that $100 million in public matching funds system would make it into the state budget. In the usual last-minute New York budget rush, Assembly Democrats fell back to a creating a commission.

The reasons for the Assembly to support public financing don’t just include virtues of public accountability and a reduction in conflicts of interest and corruption. A December 2018 study of New York’s proposed system by the Campaign Finance Institute found that every Assembly candidate would have received more funds under a public match than under the current rules.

Asked about the likelihood of the commission arriving at a public financing system this year, Carmada emphasized that its recommendations are to be binding. “If advocacy groups and New Yorkers hold their feet to the fire and they appoint serious appointees who understand and support public financing of elections,” the small-donor system is on-target to prevail, he said.

On the commission’s makeup, a Brennan Center post from April summarizes: “Under the terms of the budget bill, the commission will include nine members, with two each appointed each by Governor Cuomo, Senate Majority Leader Andrea Stewart-Cousins, and Assembly Speaker Carl Heastie. In addition, the two minority party leaders will each appoint one commission member. And the ninth and final commission member will be jointly appointed by Cuomo, Stewart-Cousins, and Heastie. The appointed commission will be required to hold a public hearing on its finding and recommendations and to produce a public report by December 1—one that becomes binding unless modified by December 22.”

Special interests and big businesses have long played a major role in New York’s lawmaking and regulatory processes, through maximum campaign contributions and the infamous “LLC Loophole”. An April 2015 article in POLITICO reported that members of the Real Estate Board of New York had given $21.7 million, over a tenth of the total, to state-level candidates in the previous cycle. A 2012 report by the Center for Public Integrity gave New York a grade of “D” in government ethics.

In last November’s election, New York City voters approved enhancements to the city’s public financing system, which forms the basis for the statewide system. A 2010 report by the Brennan Center for Justice found strongly positive effects: the number of overall contributors and the number of small donors has increased, and voter choice has increased by enabling a diverse pool of candidates with substantial grassroots support but little access to large donors to run competitive campaigns.