Update: Question One received 80% “aye” votes to 20% “nay” on the Nov. 6, 2018 general election ballot, totaling 1,151,775 votes in favor and 283,435 votes against out of a total 1,435,210.

Question Two, on an Office of Civic Engagement, was approved with 66% of the vote, and Question Three, on Community Board membership reforms, received 72% approval.

New York City Councilmember Helen Rosenthal announced her support of a ballot initiative on campaign finance reform on Monday, in an update to her previous position.

In a debate with fellow Progressive Caucus Councilmember Brad Lander on WNYC’s Brian Lehrer Show, Rosenthal said she had reconsidered and now endorsed Question One’s proposals to encourage lowering contribution limits for candidates, by increasing public matching funds available.

“I do think people should vote yes. I do think this is a great opportunity to get money out of politics. I’ve agonized over this one because the little caveat delays implementation until 2022, which will benefit incumbents, but I’ve landed on yes because in the bigger picture, I think the large reform is so necessary,” Rosenthal said on WNYC.

Prior to this morning, Rosenthal had stated opposition to Question One as formulated, because of the yearslong implementation date.

The proposal, crafted by the New York City Mayor’s Charter Review Commission, seeks to enhance New York City’s existing campaign finance program by increasing public matching funds for candidates who opt-in to the public matching program and by making funds available to candidates earlier in the campaign season.

“If you get two people to give you one hundred bucks, and it’s matched eight-to-one, you can have almost as much as the wealthiest person can give you,” Lander said on WNYC, meaning that a $100 contribution would be matched for a total of $800 in public-matching funds for qualifying and participating candidates.

The campaign finance system is also within the purview of the New York City Council’s Charter Review Commission, which is slated to present its proposals in November 2019, City & State reported in July, an election year for the Council.

The ballot measure received national attention last week when Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders Tweeted his endorsement of Question One, one of three New York City local democracy proposals receiving an “aye/nay” vote on the back of the midterm ballot.

A vote in favor of Question One has been endorsed by several good government groups, including Reinvent Albany, and national groups like the money-in-politics advocacy organization Every Voice and the public policy organization Demos, as well as the left-leaning Working Families Party.

“By adding slightly more to the city’s campaign finance budget, it will decrease the power of wealthy donors and political committees (PAC’s). Small donations will reach further and more people will be able to run for office,” the coalition in favor of Question One said on its website.

Question One was based on previous legislative proposals from Councilmember Ben Kallos, who in a blog post explained why increasing the matching amount would create more voter engagement.

“Because the current public matching program only provides a little more than half the money candidates must raise to be competitive, candidates are left to raise the rest on their own, likely with large checks, creating a big dollar gap,” Kallos wrote in a Medium post. “For city council races, the big dollar gap remains comparatively small at $68,083, which might realistically be filled with small dollars. For mayoral campaigns, however, the big dollar gap is a staggering $2.6 million, which would require tens of thousands of small contributions to fill.”

“Since 2010, over the last two citywide elections, candidates raised $128 million, with more than half coming in big money ($2,000 or more), while only 11% came from small dollars ($175 or less). This is because the city allows big money contributions of up to $5,100 and only provides public matching funds for 55% of the small dollars raised. This leaves Mayoral candidates to raise more than a third of their money — over $3 million — from the biggest donations possible,” Kallos sent Sludge in an email.

So how would it work?

“As an example of how this change would actually work, under our current system a candidate for mayor can get a maximum contribution of $5,100, and a small donor’s contribution can generate an additional $1,050 in public funds ($175 x 6). Under the proposed changes, the largest contribution a candidate could receive would be $2,000, and she or he could then get up to $2,000 in matching funds from a small donation ($250 x 8). A small contributor, donating only $250, will get most of the benefit of a large contributor,” Kallos and Morris Pearl of the left-leaning group Patriotic MIllionaires wrote in an op-ed last week in City & State.

“This gives candidates an incentive to shift their attention to raising more small donations, instead of vying for a handful of big donations. That should make politicians more sensitive to the concerns of normal voters rather than wealthy donors,” Kallos added.

In a post on his website, Lander—who represents part of Brooklyn— argues that increasing the public matching would reduce the influence of big money in politics.

“Reducing the contribution limits and increasing the match to numbers that are still high enough to communicate effectively with voters and run competitive campaigns will diminish the power of large contributors and encourage candidates to engage a broader, more diverse set of contributors. This proposal will help NYC go further in getting big money out of politics,” Lander said.”

According to the official summary, Question One was “designed to address persistent perceptions of corruption associated with large campaign contributions…”. The proposal, crafted by the Mayor’s Charter Review Commission, seeks to enhance New York City’s existing campaign finance program in several ways: by lowering contribution limits for various levels of candidates, by increasing public matching funds for candidates who opt-in, and by making funds available earlier in the process.

A 2010 report by the Brennan Center for Justice found strongly positive effects from New York City’s public financing system, the number of overall contributors and the number of small donors has increased, and voter choice has increased by enabling a diverse pool of candidates with substantial grassroots support but little access to large donors to run competitive campaigns.

“Part of the crisis in our democracy is that people are cynical, that there’s a lack of opportunity to get involved in a wide variety of ways,” Lander said Monday on the Brian Lehrer Show. Lander co-wrote another letter of support as a New York Daily News op-ed recently with Steven Choi, executive director of the New York Immigration Coalition.

As campaign finance reform measures continue to be actively opposed by Republicans nationally, and in the wake of the landmark 2010 Supreme Court Citizens United ruling, states and cities around the country have been pursuing programs to strengthen representative democracy while mitigating the influence of big money in politics.

So far, 12 states provide some form of public financing for campaigns for governor, and only five of them also do so for state legislative offices, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures.

Arizona and Maine are recognized as leaders in “clean elections” offering full public funding of campaigns, while the others offer matching funds.

The national reform group RepresentUs has identified over 24 anti-corruption campaigns in states and cities in the midterm elections, such as North Dakota’s Measure One—profiled on Ballotpedia— and a South Dakota amendment on lobbying covered last week by Sludge’s Jay Cassano. In August, Lee Drutman highlighted increasing anti-corruption messaging among leading Senate Democrats, such as Elizabeth Warren and Kamala Harris’ pledges to refuse corporate PAC donations.

Also last week, the New York Times previewed Congressional Democrats’ first ethics reforms and fair elections measures, should they retake the House after the midterms. Today, Vox’s Sarah Kliff surveyed Seattle’s experience with “democracy vouchers” for city elections – which was the topic of a Sludge event in New York City in late October, with research presented by Dr. Jen Heerwig of the Scholars Strategy Network NYC Chapter.

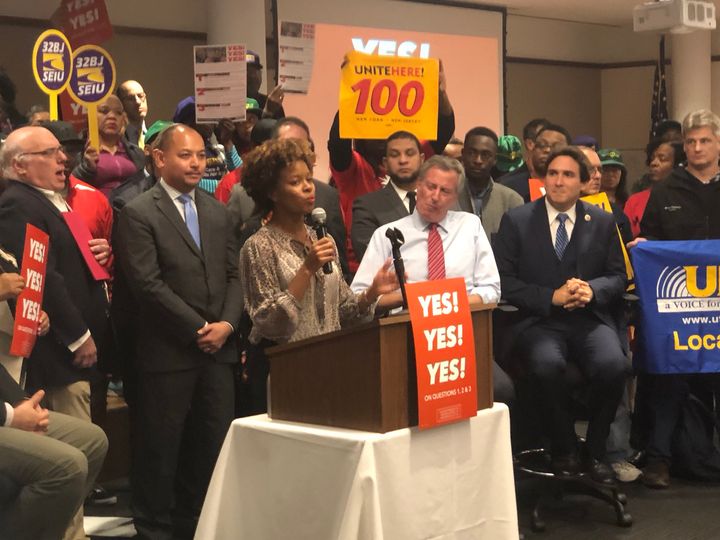

Image credit, @BilldeBlasio, Twitter, Nov. 1, 2018.