Democrats’ Public Financing Proposal Could Give Small Donors More Influence

Public campaign financing programs in states and cities across the country have grown in use by candidates and have been strengthened by voters in recent years.

When it comes to running for Congress, the amount of campaign contributions coming from wealthy donors who can afford to give the legal maximum still dominates that of small donors.

In last year’s elections, candidates for the U.S. House received, on average, less than a fifth of their total contributions from small donors who gave less than $200, according to the Center for Responsive Politics (CRP). Candidates for the U.S. Senate received an average of one-third from small donors.

Counting the presidential contest, large individual donations, those between $200 and the legal maximum of $2,800, made up 41.5% of federal candidates’ funding, while small donations made up just 22.4%, according to CRP.

A program of public campaign financing included in the Democratic reform package aims to turn this ratio on its head and ensure that candidates who are not popular among wealthy donors can still run for office and mount competitive campaigns.

The For the People Act, which was passed by the House and is now in the Senate, would create the first public financing program for congressional candidates. It would allow candidates who qualify by raising $50,000 in small donations of $200 and under from at least 1,000 individuals to opt-in to a system where further small donations they raise are matched at a 6-1 ratio. The government funds would come not from taxes, which the bill prohibits for use in the program, but from sources like a surcharge on corporate malfeasance penalties. The program would be optional, with participating candidates agreeing to abide by lower individual contribution limits and a cap on their personal out-of-pocket spending at $50,000, among other rules.

Public campaign financing programs are in place in over two dozen jurisdictions, from states to counties to cities, in versions that include grants to qualifying candidates, small-donor matching funds for qualifying candidates, and “democracy vouchers” mailed to all registered voters that candidates can redeem for funds from the government. Public financing programs, which have been used by candidates from both sides of the aisle, are in place in states including Arizona, Connecticut, and Maine, and in cities including New York, Los Angeles, and Seattle.

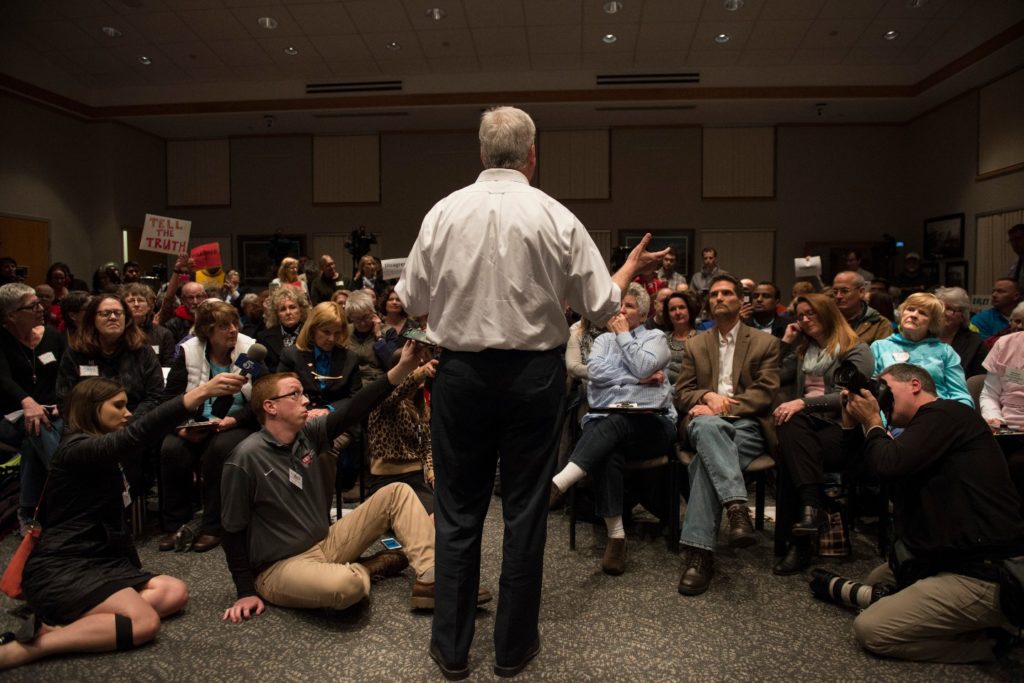

Public matching funds were adopted in 2015 by Montgomery County, Maryland, the most populous county in the state with over 1 million residents. Gabe Albornoz, vice president of the Montgomery County Council, and other elected officials who used public financing for their campaigns gave first-hand testimonials recently on the benefits of the program to the nonpartisan research institute Brennan Center for Justice, describing how it puts candidates in continual touch with voters.

“Over the course of the primary local election cycle in 2017, I visited 117 different living rooms and received contributions anywhere from $10 to the maximum $150,” Albornoz said. “I haven’t forgotten any of those conversations and I carry them with me to this day.”

Montgomery County’s matching funds model was adopted in November 2020 by voters in Baltimore County, Maryland, with 55.7% in support, after being picked up by the city of Baltimore the year before.

A Brennan Center analysis of recent elections illustrates how potent the proposed 6-1 match can be in amplifying small-dollar donations. The data show that even if just half of House candidates opted in to the program, the share of small dollars given to candidates overall would increase dramatically. The 13% raised in the 2018 cycle from small donors would have been 37% if the system had been in place and half of candidates used it.

The added incentive provided by the public matching dollars would likely further increase small donor participation numbers, and with greater participation, far more of the campaign cash to Congress would come from donations of just $200 and under.

“Under H.R. 1, almost every candidate could tap the same donors and raise the same amount of money or more, but only taking a maximum of $200 from everyone,” said Ian Vandewalker, senior counsel in the Democracy Program at the Brennan Center and one of the coauthors of the analysis of congressional contributions. With 2018’s donation figures, the share of money coming from small donors would jump from 13% to 56% when counting the match.

H.R. 1’s public matching program offers candidates another incentive to participate, Vandewalker said: saving them hours spent on fundraising calls with wealthy donors. “There’s a cottage industry in political reporting of how much members of Congress hate ‘call time,’” he said. “A public financing system can effectively eliminate call time.”

Vandewalker said that word of mouth among candidates that the matching system improves the campaigning process could spur its adoption. A report by the Campaign Finance Institute found that candidate participation in public financing programs surpassed 80% in states including Connecticut and Minnesota and cities including New York City and Los Angeles.

When Voters Get Public Financing, They Tend to Like It

Several places with public financing have seen more candidates choose to participate in the program, and many have made more funding available for their programs over time, a sign of their success.

In New York City, where the matching program has been in place since 1988, voters strengthened the public match in a 2018 referendum with 80% of voters supporting a step up in the matching ratio from 6-1 to 8-1. In the current city mayoral primary, seven of the eight leading Democratic candidates have opted in to the public match, with the next disbursement coming mid-April. The enhanced program comes with much lower individual contribution limits, $2,000 for mayor and citywide offices and $1,000 for city council, encouraging more time spent talking to voters and potential small donors than lobbyists and wealthy backers.

In 2019, the San Francisco Board of Supervisors significantly strengthened its two-decades-old public matching program, further amplifying small donations.

In Connecticut, where a public grant system has been available since 2005 to candidates for governor, statewide office, and legislative seats, 85% of candidates for the state General Assembly used the program, a report from the nonpartisan Common Cause found last year. Funded out of the sale of abandoned property, the program’s high level of participation meant that 99% of contributions to General Assembly races were from individuals, compared to in 2006, when nearly half of the money raised came from lobbyists, PACs, and other entities.

The nonprofit National Institute on Money in Politics has calculated a Competitiveness Index for state elections going back decades. Connecticut was ranked 23 of 47 states in the competitiveness calculation in its 2004 election, but steadily rose after public financing was adopted to become first in ranking for the 2018 and 2020 cycles.

Seattle is now headed into its third election cycle with the innovative “democracy voucher” program of public financing, which in its first cycle in 2017 showed success in making the donor base more representative of the city’s population in terms of age, income, and race. In its second go-around in 2019, the voucher program doubled the number of voters making donations compared to traditional cash donors, and improved the representativeness of the donor base compared with the city’s population.

In the city’s Aug. 3 nonpartisan primary election, all seven major mayoral candidates are participating in the voucher program, as are other citywide candidates like Teresa Mosqueda, at-large councilmember. She told the Brennan Center, “Not only did we hear people say, ‘Hey, this is the first time I’ve ever donated,’ but the map shows it so explicitly…. You saw people who were donating across the city in areas that had been previously redlined and have the existing consequences of redlining. So, you see higher numbers of renters and people of color who are contributing in ways that they hadn’t before.”

On May 1, voters in Austin, Texas will decide on a “Democracy Dollars’” ballot initiative, modeled after Seattle’s program, that would send one $25 voucher for each mayoral and city council race to registered voters to donate to participating candidates. The voucher proposal’s supporters in the group Austinites for Progressive Reform say the measure will increase donor diversity and voter turnout, as shown in Seattle’s experiments, and allow more people to run for office who do not already have a network of more affluent friends and supporters.

In addition to the matching funds system, H.R. 1 would create a “My Voice Voucher” pilot program in three states where eligible voters can request a voucher worth $25 that can be donated to qualifying congressional candidates in increments as low as $5. Participating candidates in the states, which are to be selected according to a “variety of geographic regions and with a variety of political party preferences,” can then redeem the vouchers for payment from the Federal Election Commission.

Comments ()